In Brian Cherney’s 1993 composition Like Ghosts from an Enchanter Fleeing, the title refers to ghosts in art, specifically in Böcklin’s painting Toteninsel, Beethoven’s Ghost Trio Op. 70, Rachmaninoff’s symphonic poem Isle of the Dead, and Strindberg’s one-act play Ghost Sonata.1 In this paper, I have borrowed Cherney’s title to refer metaphorically to the ethereal quality of quoted melodic fragments in three compositions by Cherney; my analysis attempts to define what can be perceived in these works. That which is perceptible leaves a trace. A trace is a sensually distinguishable piece of evidence demonstrating an intended meaning in a work of art; however, just because a trace can be shown to exist does not mean that it will necessarily be perceived by the listener, and if not perceived, like Bishop Berkeley’s tree falling in the forest, it has no significance.

Significance, in a discussion of contemporary non-tonal music, is a controversial topic. When the very definition of the art object is in question, the significance of elements within it is even more difficult to itemize. For the purposes of this paper, I have identified two (among many) categories of perceptible significance: possible significance and expected significance. Possible significance is that which can be derived from the melodic quotation if one follows a semantic or logical thread to a second, third or even fourth level of analogy. This is the expectation of a composer who writes for an audience who is closer in time to the events described by the composer and, presumably, more likely to be receptive to the composer’s point of view. The composer’s intended audience, then, is frequently the audience of the premiere. Expected significance, on the other hand, is significance that can easily be understood by virtually any listener, by means of generally accepted referents. This is what is expected of the accidental audience, or those who listen with interest to the work, but who do not necessarily have the knowledge expected of the intended audience.

In order for music to have significance of any kind, it must have a signifier, a perceptible sound-image, and the signifier must point to a concept embodied in this perceptible sound-image, or to that which is signified. In the absence of a pre-existent musical code, as is offered within functional tonality, many recent composers use recognizable signifiers to make their music more intelligible. One of the most successful recognizable signifiers in a non-tonal musical idiom is the tonal musical quotation. Usually, this is a familiar melody or chord progression. In this case, the signpost – the musical quotation – is the signifier, and the meaning understood by its intended audience is signified.

There are distinct advantages to quoting tonal music in a non-tonal idiom. Since semantic meaning can be gleaned from each recognizable signifier, it follows that several such quotations can be used to construct a series of recognizable signifiers, creating a narrative that enhances the experience of listening. Of course, a series of poorly chosen recognizable signifiers can also indicate unintended narratives, contrary to the intended meaning of the work, making the listening experience bewildering and ultimately unsatisfying. In addition, quotations that are too easily recognizable may overshadow the work as a whole, given the tendency of the ear to imbue the familiar with more meaning than may be intended by the composer, thereby eclipsing the unfamiliar, original, non-tonal music. The challenge in this idiom is to achieve that delicate balance, which allows familiar quotations to support otherwise unfamiliar music.

Canadian composer Brian Cherney has developed a personal musical style using a highly coherent non-tonal harmonic language combined with certain kinds of music that frequently reoccur "either literally or in an altered version, from one piece to another in cycles of inter-connected pieces. Also, many pieces contain direct quotations from, or veiled allusions to, other usually tonal music."2 I will examine his use of tonal music in three recent compositions: River of Fire (1983), Shekhinah (1988), and his orchestral work, Transfiguration (1990) to demonstrate his use of melodic quotation to create an extra-musical narrative.

In the liner notes to the Centrediscs recording of River of Fire,3 Cherney writes:

[t]he title of the work refers to the "river of fire" described in various mythologies. In Kabbalistic writings, the "river of fire" surrounds the third hierarchy of seven heavens. As each soul ascends to the highest heaven, it is led to the "river of fire" to be purified. Those souls that have undergone purification or have been pardoned during their earthly existence continue their ascent. Some souls, however, drown in the "river" and are consumed, to remain in flame until the end of all cycles of existence.

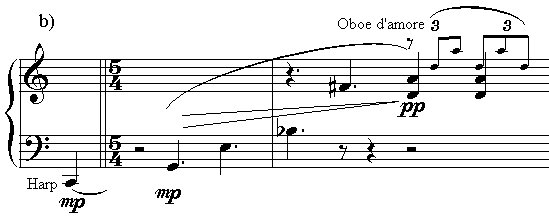

Cherney creates a sonic world to conjure up this mythical river of fire. The melody, played by the oboe d’amore, consists of contour and tone-colour, while the harp offers support: tone-colour, effects, echoes and sometimes a sort of harmonic support to the melody. He has constructed a series of impressions, consisting of timbres. Extended instrumental techniques like harmonics, bisbigliando, "rustling" glissandi, the percussive effect of striking the harp with the rubber tuning key, knocking on the body of the instrument, pedal glissandi, tone clusters, tone-splitting on the oboe d’amore, phasing techniques, all give an audible sense of otherness to the music. The most striking melodic cell consists of a rising major second, minor third, and major third:

Example One: melodic cell

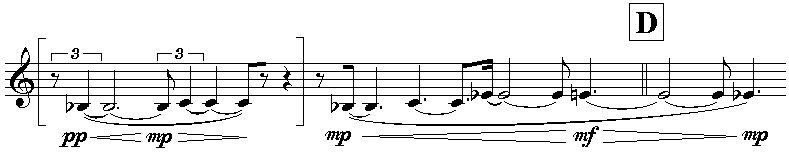

This melodic cell is a reference to Mahler’s song Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen, from the 1901 Rückert Songs, more specifically to the setting of the Rückert lyric, "I have lost track of the world."4 Significantly, Cherney does not quote directly from the song. Instead, he imitates the gesture, (the rising gesture: B flat-C-E flat-[E-E flat] and the descending gesture: A-G-E flat-C-D-B flat) rhythmically transformed, and clearly heard for the first time one bar before rehearsal D5:

Example Two: Brian Cherney River of Fire

Motives, important as they are in River of Fire, are not the only element inspired by the Mahler-Rückert song. The instrumentation is also crucial to establishing mood in the work. The timbral qualities of the Mahler song, that focus on the qualities of the cor anglais and the harp, match the sonic intentions of River of Fire (in River of Fire they are for harp and oboe d’amore, which is closely related to the cor anglais); in both works, these timbres can been heard as intimations of the afterlife.6

The text of the Mahler song refers to mental and physical states similar to those described in the Kabbalistic heaven – a place of repose experienced by the dead. Mahler chose his signifiers carefully: the instrumentation and the lyric evoke the spirits of the dead. The symbolic importance of this reference in River of Fire is highly relevant; as a work dedicated to the memory of a relative (Cherney’s grandfather, Alfred Green), and simultaneously referring to the mythological river of fire, it is crucial that the piece make clear that the river of fire described is a place where the dead may attain solace.

The depiction of otherworldly solace has been attempted many times before; in his late works, especially Prométhée, Russian composer Aleksandr Scriabin used the "mystic chord", which he referred to as the "chord of the pleroma." The "pleroma", according to Richard Taruskin, is

a Christian Gnostic term derived from the Greek for "plenitude" ... the all-encompassing hierarchy of the divine realm ... Its preternatural stillness was a gnostic intimation of a hidden otherness, a world and its fullness wholly above and beyond rational or emotional cognition.7

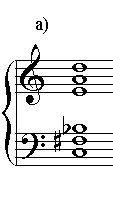

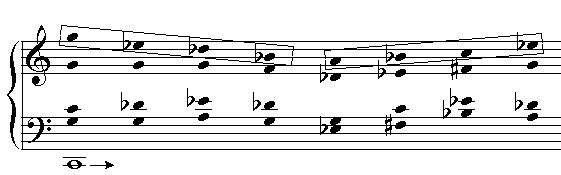

This description is strikingly similar to Cherney’s description of the Kabbalistic "river of fire." The chord, (is almost identical to the motif that characterises the music of solace in River of Fire:

Example Three: a) Scriabin’s mystic chord b) Cherney River of Fire, letter H

Cherney, however, was unaware of this resemblance to the mystic chord. In an email, he wrote: "I was not consciously using Scriabin’s mystic chord. I chose this chord because I liked the sound of it with that particular spacing."8 The similarity of Cherney’s arpeggiated chord to Scriabin’s was not deliberate (although it may have been subliminal on his part) and yet in both works the chord is virtually identical, suggesting that active listeners create connections that were not intended by the author, but which are nevertheless relevant. On the other hand, it could suggest there is something genuinely evocative of solace in this chord; something greater than what the mind of any individual composer could create.

The state of mind suggested by the words solace, comfort, or consolation, like stillness,9 is a relative condition, and it cannot exist without its opposite: tension. River of Fire draws upon several powerful consoling factors, in the tone colour of the harp and the oboe d’amore and possibly recognizable melodic fragments. The most effective consoling factor though is a repeated chord progression played by the harp, consisting of the "I have lost track of the world" motif (in descending form: G-E flat-D flat-B flat, and in ascending form: A-B flat-C-E flat), harmonized in a non-tonal manner, over a low C drone, at figure N, as seen in example four:

Example Four: Brian Cherney River of Fire, letter M through letter P (reduction)

This pattern serves as a sort of musical background of increasing and decreasing tension, which is consoling because it is defined by known harmonic and melodic parameters, but also vaguely disturbing because it goes out of phase with the oboe d’amore melody by one quarter-note each time the locus of the melody changes during this graphically notated section. Another element that contributes to this tension is not something that can be cognitively perceived by the listener: the section is notated in a deliberately obtuse configuration, which may alienate the performers, thereby increasing their (perhaps subconscious) level of tension in the performance.

When this modularly notated section is complete, the music immediately following is made up of an oboe d’amore melody based on the inverse of the motif from example one (descending major second, followed by a descending minor third – C-B flat-G), accompanied by a repetitive pattern based on the music of solace from example four on the harp. After the high point of the work, these familiar elements give a sense of comfort, and because the melody outlines the inverse of the setting of the Mahler lyrics ("I have lost track of the world"), may suggest salvation (perhaps: "I have gotten back on track of the world"). The final consoling factor is a repetition, in the dying measures of the work, of the introduction, which brings to mind a highly stylized ABA structure. Such hints of familiar elements allow the listener to create patterns of recognition in a work that is otherwise extremely dense.

Shekhinah (1988) for solo viola, uses signifiers in a more personal manner.10 It was inspired by a photograph published in the Montreal Gazette on March 19, 1988, accompanying a review of the book The Holocaust in History by Michael Marrus.11 The photo depicts a procession of women and children; Cherney subsequently discovered it had been taken at Auschwitz. The composer describes his inspiration in a note, published with the score:

My attention was particularly drawn to one of the women in the photograph – a striking figure with a shawl over her head, taller and younger than most of those around her. Her bearing and facial features reminded me, in an uncanny way, of the violist Rifka Golani, for whom I was about to write a work for unaccompanied viola. The idea then occurred to me to write a work for that woman in the photograph, dedicated to her memory. I hoped thereby, in some small way, to rescue her from anonymity and oblivion.12

Anonymity and oblivion is the fate of the anonymous victim, the signified without a signifier, and so Cherney named the piece Shekhinah to relate this nameless woman to womanhood, to divinity, and to Judaism.

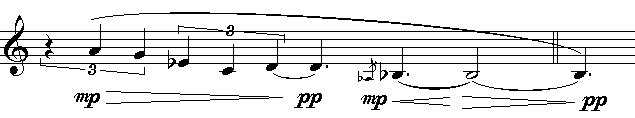

The term Shekhinah is the name given to the female aspect of the divinity in the Kabbala. It is a passive, receptive, mystical embodiment of the community of Israel; it is also the only aspect actually experienced by the Kabbalists.13 There is a double relevance to Shekhinah: on an individual level, it is a memorial to the anonymous woman in the photograph, but on a broader level, it is a representation of female divinity, which consists of three archetypes, nefesh, ruah and neshamah: daughter, bride and mother. Nefesh is described as "restless and unstable ... made up of trills, glissandi and quickly moving passages"14 and the opening of the work depicts this archetype. Cherney composed a lullaby in a minor mode, reminiscent of Eastern European Jewish folk melody, as a sign of the neshamah, or mother aspect of the female divinity:

Example Six: Brian Cherney Shekhinah, bars 70-73

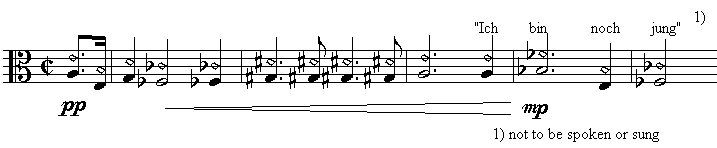

Immediately following the first statement of the lullaby, there is a reference to Schubert’s song "Death and the Maiden," a representation of the bride, the ruah, the sexual element of the divine selfhood:

Example Seven: Brian Cherney Shekhinah, bars 112-15

A fragment of an untitled partisan song from World War II follows soon after, followed by the melodic setting of the line "ich bin noch jung," from "Death and the Maiden":

Example Eight: Brian Cherney Shekhinah, bars 121-25

As a topos, "Death and the Maiden" depicts one of the first artistic connections between death and sexuality, a connection collectively referred to as a danse macabre. The earliest known reference to "Death and the Maiden" is in the 1517 painting by the Swiss Reformation painter Niklaus Manuel Deutsch (1484-1530).15

The musical material of "Death and the Maiden" is intervallically linked to the fragment of the partisan song, allowing the listener to join the two aurally, suggesting defiance in the maiden’s statement "ich bin noch jung" (I am still young). The fragment of the partisan song is stated using harmonics, giving it an otherworldly quality. It is also played in dotted and cut rhythms, suggesting a children’s mocking chant. Nevertheless, after it is treated in bars 121-35, it is never referred to again, while "Death and the Maiden" is fragmented, transposed, and finally distorted until it is utterly unrecognizable.

What is remarkable about the construction of Shekhinah is the dialectic between recognizable elements – the lullaby and the two songs – and the atonal elements. As a memorial to the unknown woman in the photograph, the work takes elements of her perceived character – mother, bride, and daughter – as well as elements from the world in which she lived. The partisan song corrupts the statement of "ich bin noch jung," suggesting the futility of defiance as well as a morbid irony in the face of certain death. The lullaby suggests her only apparent means by which to defeat death, in the form of the immortality afforded by motherhood.16

The song "Death and the Maiden" is in German, the language of the unknown woman’s oppressor. But perhaps even more significant to the intended audience is the fact that it was quoted by George Crumb in his 1970 electric string quartet Black Angels, which was inspired by the Vietnam War.17

Cherney’s inspiration, in addition to the commission from violist Rifka Golani, was the anonymous woman pictured in the photograph. The soul of the woman, who almost certainly died shortly after this photograph was taken, is offered transcendence in the music. The significance of the fact that Rifka Golani, who resembles this anonymous woman, was playing the work at its premiere, would have added poignancy to the premiere.

Not only did Cherney give immortality to this unknown woman in Shekhinah, but also he revived her memory in his 1990 orchestral work, Transfiguration.18 This work is dedicated to Raoul Wallenberg, the Swedish diplomat who, as a member of the Swedish legation in Budapest during the last month of World War II, saved thousands of Jews who would otherwise have been sent to death-camps. He was arrested by the Red Army following the war, and has not been seen since.19 Early on in the work, (bars 2-10, 38-48) three solo violas begin playing the opening nefesh (daughter) section of Shekhinah, and later, about two-thirds of the way through Transfiguration (bars 233-62), Cherney quotes extensively from the same nefesh (daughter) section, beginning with a solo viola, and gradually dividing the figure between seven violas. This quotation has metaphorical significance in Transfiguration. The single woman that was memorialized in Shekhinah is duplicated to represent the many people who were saved by Wallenberg. In semiotic terms, the trace of the lost woman can be seen in the memory of the lost Wallenberg, as represented in the orchestral piece.

"Death and the Maiden" is quoted in bars 117-20 of Transfiguration by the bassoons, trombone, tuba, violas and contrabasses, in intervallic augmentation, including a temporal augmentation of the "ich bin noch jung" melody, bars 120-24 on the solo viola, and in at bars 204-5 in all the strings.

The symbolic importance – in context – of these melodies is great: although the initial, static melody of "Death and the Maiden" is bolstered by enhanced orchestration in Transfiguration, it has also been altered, giving it only a faintly recognizable character. Only the macabre "ich bin noch jung" quotation is quoted verbatim, and in fact, it is given strength by increased dynamic markings, and by the fact that it is played in the midst of an otherwise quiet, yet large orchestra.

The word transfiguration, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, means "a change in form or appearance, especially so as to idealise or elevate." Raoul Wallenberg’s actions during the dying days of World War II are those of a saviour from the perspective of a Hungarian Jew. If one were to create a narrative based on the signifiers in the work, it would not be difficult to see the indomitable spirit of the Shekhinah, the transformation of death, and the strengthening of the desire to remain young by the augmentation of the melody associated with "ich bin noch jung." As a mimesis, the composition contains all the elements of the memory of Raoul Wallenberg.

An analysis based on the perceptible, rather than the intended meaning, [this is referred to as an esthesic analysis] relies on various levels of intelligibility in its signifiers. To achieve this, Cherney has chosen to quote or refer to material either with known significance or recognizable attributes to its intended audience. By choosing the melodies he did, from Mahler’s Rückert Songs, Schubert’s "Death and the Maiden," the untitled, wordless partisan song, and the composed tonal lullaby, Cherney has provided a set of recognizable signifiers, producing a series of evocative, but not entirely understood images, that appear and disappear – like ghosts from an enchanter fleeing – within and through the musical fabric. The cumulative effect of this game of musical hide-and-seek is impressionistic in its aesthetic, yet, in the end, remains entirely consistent with his musical language.