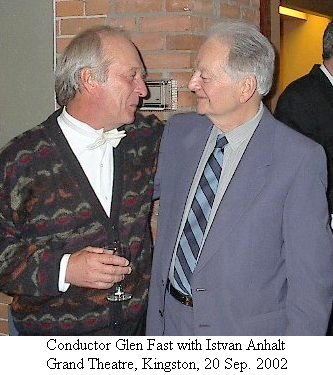

At 83 years of age, composer Istvan Anhalt shows no signs of slowing down. Indeed, the years since his retirement in 1984 have been the most productive of his career, with major works for orchestra, voice, and string quartet, plus two large-scale operatic works, Traces (Tikkun) and Millennial Mall. The latest installment in his impressive post-retirement output, the orchestral work Twilight~Fire (Baucis’ and Philemon’s Feast), was premiered September 29th, 2002 by the Kingston Symphony at its regular concert venue, the Grand Theatre. It was a significant occasion, marking as it did the first time that an Anhalt work has been premiered in the city he has called home for the past three decades. Local composers turned out in force for the premiere, including Kristi Allik, John Burge (whose new Trumpet Concerto is to be premiered by Stuart Laughton with the Kingston Symphony on January 12th, 2003), F.R.C. Clarke, Alfred Fisher and Marjan Mozetich. Glen Fast, who is currently in his twelfth season as Music Director of the Kingston Symphony, led a polished and well rehearsed performance of this intricate and involving new work.

Twilight~Fire was written to celebrate the golden wedding anniversary of Istvan and Beate Anhalt (who were married on January 6th, 1952). The subtitle alludes to the story in Ovid’s Metamorphoses about an elderly couple who offer shelter and a humble meal to two strangers, who turn out to be Jupiter and his son Mercury. As repayment of their kindness, Jupiter grants their wish to die together and turns the couple into two trees. As Anhalt wrote in his programme note for the work, "Without ever entertaining the idea of a piece in the manner of ‘program music’, which had no appeal for me, I hoped that the sounds of the new piece would somehow evoke the spirit of this antique Greek story."

Intricately scored for a classical orchestra of double winds and strings with added percussion, keyboard and harp, the work opens and closes with both conductor and players immobile and silent for about 20 seconds. Two solo violins lead off the work with an expressive melody to which other instruments are gradually added. The tempo is prevailingly slow and the gestures appropriately delicate and intimate in the first half of the piece. A striking feature of the second half is a series of improvisatory cadenzas, for harp, clarinet, flute, and celesta over a sustained chord in the strings. The work ends in a mood similar to the beginning; Anhalt notes that the music of the concluding bars, scored for solo viola and cello, resembles "two trees standing close to each other with their branches intertwining, suggesting a couple in an ageless embrace." The work, which was tailor made for the Kingston Symphony, is a fine addition to the repertoire. Report by Robin Elliott

The premiere of Brian Cherney’s double concerto La Princesse lointaine (by the Toronto Symphony on Wednesday, November 27th, 2002 at 8:00 pm in Roy Thomson Hall, with two subsequent performances on the 28th and 30th) demonstrated the musicians’ love of contemporary music. The orchestra, under the direction of Christopher Seaman, the music director of the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra, began the concert with Elgar’s Cockaigne Overture, turning in a rather ragged and lack-lustre performance, but something happened between the end of the Elgar and the beginning of the Cherney piece. Maybe the orchestra likes to play quietly – I don’t know – but whatever it was, was heartening for Canadian music.

The work was commissioned by the CBC for the harpist Judy Loman, the english hornist Cary Ebli, and the Toronto Symphony, all of whom played beautifully. Cherney has a knack for writing music that is shy and yet extroverted, idiomatic and impressive to the ear. Like George Crumb’s early music, his work is highly attuned to the nuances of beauty. Cherney named the composition La Princesse lointaine because he saw in the double concerto a sort of relationship as though between two people, and this attraction - separation idea reminded him of the long and convoluted bond between Irish nationalist Maud Gonne and the Irish poet W.B. Yeats.

The texture of the work is fine and carefully wrought, with microscopic changes in texture and colour. The strings could frequently be heard fingering notes without bowing them, and the clicking of the woodwind instruments lent an ethereal quality – as though we were in the presence of hordes of busy insects. As Cherney writes in his programme note, "the orchestra provides connective tissue, colour, amplification, commentary, and even disruption." And so it does, but it also contributes much more. The shape of the piece was carried along by the melodic qualities in the orchestra’s music more than that of the soloists, and the result was a highly structured and delicately wrought piece, the best I have heard to date by Cherney. He has a real affinity for double reeds and harps; it is hard to say just how it happens, but the combination of these two sounds gives the music a distinctly Cherney-esque quality. The language is a sophisticated non-tonal idiom, distinct and divorced from any "ism"; it is a personal style based, it seems, on the whims of his ear. And Cherney’s ear is one that is remarkably adept at choosing chords and timbres which are neither jarring, nor overly delicate. His music is quietly robust and moving, in a cerebral way. While the work is not programmatic, the musical logic was well-conceived, extending its arc over the full 18 minutes, and leading logically to a satisfying conclusion. Report by Sandy Thorburn