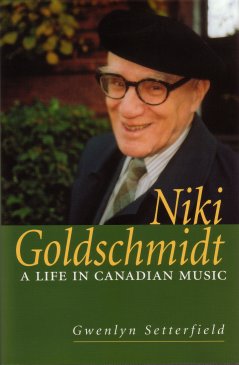

Gwenlyn Setterfield. Niki Goldschmidt: A Life in Canadian Music. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2003. xv + 222 pp., ill. ISBN 0-8020-4807-2. $50.00 (cloth).

Though he has been professionally active as a pianist, conductor, singer, artistic director, and even (on rare occasion) composer, Nicholas Goldschmidt’s main occupation in the course of nearly 60 years of residence in Canada is best summarized by the French word animateur. No English word or phrase gets the point across quite so elegantly and precisely. The exact translation – animator – is coloured by its association with those who create cartoon films. Other English terms one might use – ideas man, go-getter, catalyst, man of action – are too pedestrian or crude. Perhaps that is a reflection of the fact that so few native English speakers have excelled in Goldschmidt’s chosen arena. He has been one of the great enliveners of Canada’s cultural life, and especially of musical activity, since arriving here in 1946. He is, in short, someone who makes things happen.

A consideration of Goldschmidt’s talents might begin with the fact that his father was born in Berlin, and his mother was ‘from a distinguished Viennese family’ (p. 8). Goldschmidt seems to combine the stereotypical traits of the inhabitants of these two cities, which are in many ways diametrically opposed: he has the Berliner’s hard-nosed, eminently practical, and distinctly realistic approach to life, but tempered by the Viennese flare for charm, graciousness, and elegance. The Berlin side of his character enables him to sketch out with uncanny accuracy, in his head and on the backs of envelopes, a festival budget that runs to over $3 million (p. 167), at the same time as the Viennese side plans out the elements that will make the festival an artistic success.

Goldschmidt was born in 1908 on his family’s 30,000-hectare estate in Moravia, not far from Brno (or Brünn as his family would have called it). It was the twilight years of the Hapsburg empire, and indeed of an entire way of life. Goldschmidt and his five brothers were educated at home by private tutors, becoming fluent in German, French, and English, but were left to their own devices to pick up Czech, the language that surrounded their diasporic idyll. Twice a year the boys sat their academic examinations in Vienna, 120 km to the south, and it was to Vienna that Nicholas returned in 1927 for advanced studies at the music academy. His instructors there included Corneil de Kuyper for voice and Joseph Marx for composition; Herbert von Karajan was a fellow student. The six year course of study was completed in 1933, after which he began working his way up the ranks in a variety of small municipal opera houses. One of these positions took him to Troppau (Opava in Czech), a small town in northern Bohemia; there he crossed paths with Irene Jessner and Herman Geiger-Torel, both of whom he would later work with in Toronto.

On the sage advice of a politically astute uncle, Goldschmidt emigrated to the U.S.A. in 1937. He refuses to regard himself as an émigré, though, and indeed his departure was not necessitated by either artistic reasons (he was in no way prone to avant-garde tendencies, as were such émigrés as Hindemith and Krenek) or religious persectution (for his mother was Catholic, not Jewish). The migration to America was an astute career move rather than an ‘exile to paradise.’ He worked at various musical jobs in New York and San Francisco, and then produced foreign language news broadcasts for the Office of War Information for a year. On the invitation of Arnold Walter, he moved to Toronto in September 1946 to become music director of the Opera School of the Toronto Conservatory of Music. Two years later he married Shelagh Fraser, the daughter of a well-to-do Scottish immigrant (her father was the first provincial archivist and later served as aide-de-camp to the lieutenant-governor). Toronto has remained home base for the Goldschmidts ever since.

Goldschmidt’s energetic work for the Opera School is captured in the dated but still very enjoyable NFB film Opera School (1952), in which he appears alongside Walter and Geiger-Torel. After quitting the Opera School in 1957, Goldschmidt went on to found the Vancouver International Festival (1958-62), serve as chief of Performing Arts for Canada’s Centennial Commission (1964-67), direct musical activities at the University of Guelph and the Guelph Spring Festival (1967-87), run the Algoma Fall Festival in Sault Ste Marie (1973 on), organize the International Bach Piano Competition (1985), three ‘Joy of Singing’ choral festivals (1989, 1993, 2002) and ‘The Glory of Mozart’ festival and competitions (1991), and set up Music Canada Musique 2000, which helped to finance some 60 music commissions for the Canadian millennium celebrations. It all sounds like, and no doubt was, enough to keep a dozen men busy, but thanks to his boundless energy, his great sense of timing, and the unflagging support over the past 55 years of his wife, it was accomplished by Goldschmidt alone.

Not everything that Goldschmidt undertook was an unqualified success; some of his projects turned sour before they were even hatched, and others began well but lost momentum or lost money (or both) as they went along. But his track record was better than most, and the number of artists whose career he has launched or furthered, and of organizations he has founded or enriched, is legion. He continues to be very active, setting a pace of work at age 95 that would be the envy of many people half his age. A University of Toronto graduate student who wanted to interview him last year contacted his office to set up a meeting, only to find that at the scheduled time she had to speak with him on the subway as he raced from one appointment to the next. He is indeed busy, but he is also guarded, and still seems to be too preoccupied with the present and the future to dwell much upon his past.

The present biography gives some measure of Goldschmidt’s many accomplishments, but the man behind these various missions remains something of an enigma. Indeed, the reader learns almost as much about Goldschmidt the man from Teresa Stratas’s engaging foreword as from the rest of the book. The author had full access to Goldschmidt’s papers at the Library and Archives of Canada, as well as other archival sources, and also a series of taped interviews with Goldschmidt that Susan Hayes and Maria Muszynska made between 1998 and 1999. She interviewed Goldschmidt and his wife on several occasions (presumably in their home rather than on the subway) and hunted up many people who have been associated with him over the years. But despite the meticulous research, the book flags often, and at times it even goes off the rails altogether for a paragraph or two (one really begins to wonder about the quality of copy editing at UTP these days). At its best this is a competent and even engaging recital of facts, but it never probes very deeply. The excitement that Goldschmidt knows how to create in the theatre or the concert hall is lacking in this simple narrative account of his life.

Ashley MacIsaac, with Francis Condron. Fiddling with Disaster: Clearing the Past. Toronto: Warwick Publishing, 2003. 279 pp., ill. ISBN 1-894622-33-2. $18.95 (paper).

Sex and drugs and … Cape Breton fiddling. That pretty well sums up the contents of this tell-all autobiography. Though only 28 years old, Ashley MacIsaac has been living in the public eye for a long time. He appeared at first in Cape Breton as a step dancer while still a child, then toured around Atlantic Canada as a fiddler in his teens, and finally performed across Canada and inter-nationally in the wake of the huge success of his CD hi™ how are you today?, released in 1995.

MacIsaac came to the attention of the wider world at the age of 17 when he was invited by JoAnne Akalaitis to perform in a New York City production of Woyzeck with music by Philip Glass. She had heard MacIsaac play while holidaying in Cape Breton. The gig lasted for only three months, but it was to change MacIsaac’s life forever. For one thing, it brought home to him the fact that his brand of Cape Breton fiddle music, blending Scottish and Acadian roots with other more modern influences, could tap into the insatiable worldwide demand for Celtic music in the mid-1990s. For another, living in New York City allowed him to come to terms with his gay sexuality, something that was just not possible for him in Cape Breton.

The revelations in chapter six, ‘Drugs,’ come fast and furious. MacIsaac began with soft drugs but then discovered crack cocaine. Pot made him mellow and acid enhanced his creativity, but crack ended up destroying him: ‘I got really screwed up physically in my lungs, and lost all my money, and almost lost my career and all my friends and family. It took all that shit happening to get me off it; I had to get almost to the very bottom before smoking crack was no longer enjoyable to me’ (p. 131). What remains is an abiding love for smoking marijuana, which in MacIsaac’s view is not only harmless but positively beneficial, as it prevents him from returning to harder drugs.

There is much vitriolic comment in the latter part of the book on the Maclean’s profile which threw MacIsaac’s life into a tailspin from which he is still recovering.1 It is MacIsaac’s contention that the press turned on him because he was not only gay but also openly sexually active. His view has some merit, but it minimizes the effects of his drug habit and increasingly erratic onstage personality in creating a bad press. That hard drugs, onstage profanity, and personal destruction go hand in glove will be familiar to anyone who has seen Dustin Hoffman’s portrayal of stand-up comedian Lenny Bruce in Bob Fosse’s film Lenny (1974). At one point MacIsaac was so desperate that he tried to pawn his violin for $25 to get his next hit of crack. The wonder of it is that he did not die of a drug overdose, as Lenny Bruce did, but rather quit using hard drugs cold turkey. In the meantime, though, he managed to run through an estimated $10 million in five years; his explanation of where all the money went should be required reading for any aspiring pop music performer.

This book, deftly ghosted by Francis Condron, is breezy and colloquial in tone, well paced, and hard to put down. None of the extensive secondary literature on MacIsaac (both popular and scholarly) is cited, but the book includes a useful index, a discography, and eight pages of black and white photos.