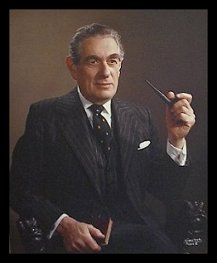

The musicologist Harvey Olnick died in Toronto on October 30th, 2003 at age 85. He was educated in his native New York at The City University of New York and Columbia University, completing the MA degree at the latter institution in 1948. Olnick moved to Toronto in 1954 and remained there until his death. He taught from 1954 to 1983 at the Faculty of Music in the University of Toronto, and kept up a lively interest in the faculty thereafter. His areas of specialty were Italian baroque music and Beethoven, but his interests ranged widely over the entire history of European art music. When the Graduate Department of Music at the University of Toronto was founded in 1954, Olnick served as founding secretary until 1971 (the position was renamed chairman in 1968). He was instrumental in setting up the university’s electronic music studio (an interest he did not keep up after the 1960s), and was on the planning committee for the construction of the Edward Johnson Building. He became a senior fellow at Trinity College, University of Toronto in 1963, won the Ontario Confederation of University Faculty Associations teaching award for 1981, and was made a professor emeritus upon his retirement.

Olnick is often regarded as the founder of serious musicological study in Canada. He concentrated on teaching, building up the profile of music and musicology, and creating a significant music research library at the University of Toronto, at the expense of his own scholarly publishing. Of his published work, the finest item is an article on Harry Somers, written for the Canadian Music Journal (vol. 3, no. 4 [Summer 1959]: 3-23). When I praised this article to him once, Olnick modestly and characteristically dismissed it out of hand: ‘That was just some propaganda I wrote as a favour to Harry’ was how he put it. It is, of course, very much more than that: it is a thoughtful and literate critique, combining a probing character portrait of the 33-year-old Somers with a dispassionate and informed analysis of his most important compositions, including a fine discussion of the Third String Quartet, which had been completed just a month or so before the article was written.

Although resident for so long in Toronto, Olnick in many ways remained American in outlook until the end. Indeed, one of the main attractions to the position in Toronto for Olnick was the easy proximity to New York City. He was a faithful reader of the New York Times up until his death, and one of his proudest accomplishments was to get the American Musicological Society and the College Music Society to hold their joint annual meeting in Toronto in 1970 (the first time this meeting was held outside of the United States). He was involved with the Marlboro Music Festival in Vermont (a reflection of his love for the chamber music repertoire), as director and leader of the collegium musicum from 1956 to 1958, and as a board member thereafter.1

Olnick was born in New York City on 18 December 1917, and he grew up in Oyster Bay on Long Island. His parents were musical and often took him to concerts – he heard Rachmaninoff and Paderewski at Carnegie Hall and attended concerts and rehearsals of the New York Philharmonic under Toscanini. At the age of six and a half he enrolled in the Institute of Musical Art (later the Juilliard School) for lessons in piano, music theory, singing, and Dalcroze eurythmics. He commuted to New York three times a week (on his own from the age of nine), while at the same time attending regular school.

His studies at CUNY were in physics and mathematics. Olnick acquired the BSc degree in 1940, and later put this learning to use in the University of Toronto’s Electronic Music Studio. He began graduate studies at Columbia University in 1941, but war service soon intervened. During the Second World War Olnick trained for the United States Air Force and acquired a commercial pilot’s license, but due to his red/green colour blindness he could not fly during the war and so instead completed his war service as a meteorologist.

Olnick’s initial musical interests centred on performance and composition. As a student he explored the piano four-hand repertoire with his brother (who was six years younger) and he also composed in the style of Brahms. He destroyed all his compositions when his interest turned to musicology. As a graduate student at Columbia University he studied with Paul Henry Lang and Erich Hertzmann, and also briefly with Manfred Bukofzer, for whose book Music in the Baroque Era (New York: Norton, 1947) Olnick had an abiding admiration. Other musicologists whose lectures and presentations Olnick was able to attend included Gustave Reese, Curt Sachs, and Oliver Strunk. His graduate work at Columbia centred on early 18th century instrumental music in Paris; he completed the course work and exams towards a doctoral degree, but did not write his dissertation.

After teaching at Vassar College for a year Olnick was awarded a Fulbright scholarship to travel to Italy and study the early sources of the baroque concerto. In the spring of 1954 he was invited by Arnold Walter to the University of Toronto to assume the first position in musicology to be created at a Canadian university. Olnick found that Walter wanted a musicologist on staff for academic respectability, but that his real interests lay in performance. Disillusionment would have set in quickly for Olnick but for the comradeship and mutual support of two fellow staff members: John Beckwith and Godfrey Ridout. With the latter in particular Olnick developed an extremely close friendship. ‘He was a fixture at our Sunday evening family dinners,’ remembers Ridout’s daughter Naomi, ‘and was godfather to my brother Michael. After my father’s death in 1984 he remained in very close contact with my mother and the rest of the family.’ Olnick contributed a fine article on Ridout to the Encyclopedia of Music in Canada. Jonathan Freeman-Attwood (who is Vice-Principal and Director of Studies at the Royal Academy of Music in London and a former pupil) recalls that Olnick was a considerate and caring companion to friends in need: he nursed Freeman-Attwood’s aunt through her last twelve years, for instance. ‘His modesty and sense of privacy meant that these gentler aspects of his character were not always recognised,’ Freeman-Attwood notes.

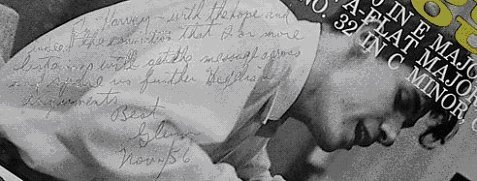

Olnick also had a close but on occasion adversarial association with the pianist Glenn Gould in the 1950s. Gould sent Olnick a copy of his recording of late Beethoven piano sonatas, and on the cover [pictured left] inscribed it as follows: ‘To Harvey – with the hope and indeed the conviction that 2 or more listenings will get the message across and spare us further Hegelian arguments. Best, Glenn, Nov/56’.

Throughout the 1960s Olnick worked hard at developing the music curriculum at the University of Toronto, pioneering not only the graduate programme in musicology, but also undergraduate offerings in the Faculty of Arts and Science. His commonsense view was that it is equally or perhaps even more important for the university to develop educated listeners as well as professionally trained musicians. For many years Olnick taught the introductory music course for the Faculty of Arts and Science himself. At the same time, he built up a specialist undergraduate programme in musicology at the Faculty of Music. Survey courses meeting for one hour a week had been the norm previously; Olnick introduced specialized courses that met for three hours a week, and the scope of the music history curriculum was broadened to encompass everything from medieval to modern music.

Faculty development was another priority for Olnick beginning in the 1960s. His former student Rika Maniates was the first musicology appointment that Olnick made, in 1965, followed by Robert Falck in 1967. Christoph Wolff from Germany was appointed in 1968 but left in 1970 and was replaced by Carl Morey (another former pupil).2 Other appointments made while Olnick was chairman of the music history division included Andrew Hughes in 1969, Gaynor Jones in 1972, and Timothy McGee in 1973. With the exception of Wolff, all of these appointees were still on staff when Olnick retired.

Olnick could be an intimidating presence, both inside and outside of the classroom. He did not suffer fools gladly, had neither the time nor the inclination for small talk or trivialities, and was impatient with students if he felt that they did not give of their best and have something worthwhile to contribute. He liked to point out that those who were not serious about their studies were not just wasting his time and their own, they were also wasting taxpayers’ money. Students were expected to come to class fully prepared to discuss the music in detail, with well studied scores in hand. Those who did not measure up to his standards could receive stern treatment and not a few were expelled from his classes over the years. But for those who weathered the storms and found favour in his books, he was an inspiring and extraordinarily helpful mentor. His pupils went on to occupy leading positions in the academic world of music across Canada and abroad. He was singularly proud of their accomplishments and always liked to hear of their activities, preferably at first hand.

Olnick was an inveterate pipe smoker for many years, enjoyed good food and a fine glass of wine, dressed well, and lived on his own in an immaculate and beautifully furnished apartment in Sutton Place on Bay Street, just a seven minute walk from the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Music. He was, in fact, a wine connoisseur: he belonged to several wine clubs and was able to discuss details of oenology with the professionals. He was also knowledgeable about art and had catholic taste in that area, ranging from classical antiquity to modern Canadiana. A particularly fine canvas by Ken Danby, acquired before the artist became famous, was the pride of his own small but handsome private collection. Olnick was also a talented amateur photographer in his youth. In his last years he was forced to use a cane and then a wheelchair, and he had to cope with various health problems, including macular degeneration, a progressive loss of hearing, and an embolism. He died peacefully, sitting in his wheelchair in his apartment. A well-attended memorial gathering was held at Trinity College, University of Toronto on 22 November 2003.