[H]e eats cake out of pastry windows and is hungrier and more potent and more powerful and more omni-verous than the paper-mâché lion run by two guys and he is the great earthworm of lucky life filled with flowing Chinese semen and he considers his own and our existence in its most profound sense.1

The huge dragon puppet that wends its way through Vancouver’s Chinatown at Chinese New Year is not only a visual spectacle and an exotic messenger of good fortune and vitality, but also a player in an exciting musical drama. Alexina Louie, who was born in Vancouver in 1949, once followed the dragon past the shops of Chinatown, where she had lived as a child. Microphone and tape recorder in hand, she recorded the loud drum rolls and the clanging of cymbals that accompanied the brightly coloured dragon. Her father thought she was ‘off her rocker,’ Louie said, but ‘I knew that I’d use the dance some day in my music.’2

She was right. The sound of the dragon can be heard in her orchestral work The Eternal Earth (1986), and it also features in her chamber composition Demon Gate (1987) and in Music for Heaven and Earth (1992), an orchestral work that calls for four percussionists. The dragon parade is the kind of sound that is one of the distinguishing features of Louie’s music, which frequently includes distinctively Asian references. But it was not until Louie was an adult with a degree in piano performance, a B.Mus. from the University of British Columbia and an MA from the University of California at San Diego that she began to study her Chinese musical heritage.

In California, her composition teachers Robert Erickson and Pauline Oliveros had challenged the shy, conservative Canadian with the newest ideas about chance and indeterminate music. After graduation, she was so in need of time to assimilate all she had learned and experienced that she stopped composing for years:

From 1973 to ‘78 I read a lot, all the things that inspire me now – oriental literature and philosophy, I studied the Chinese zither, the ch’in, and tried to fashion my own voice with a very specific oriental flavour. Oriental music touched me deeply, even though I’m a third-generation Canadian and grew up practising Bach and Beethoven.3

The ‘oriental flavour’ that Louie desired sounds foreign to Western ears not only because of its melodies, but also because of its rhythms, the aspect of her music this essay will explore. Diane Bégay wrote

[Louie] revels in complex rhythmic structures. Dizzying changes of meter and swirling kaleidoscopes of rhythmic patterns are aspects of her music that she thoroughly enjoys.4

When the pianist Jon Kimura Parker heard one of her chamber works, Music for a Thousand Autumns (1983, revised 1985) for the first time, he was impressed by her use of ‘exotic percussion instruments and piano to achieve unusual timbres and effects.’5 It may have been Louie’s rhythmic sophistication that prompted Mavor Moore to write, after hearing one of her compositions on CBC radio, ‘I wondered whether anyone missing the opening credits could have guessed whether the composer was male or female.’6 As Louie’s music is often both introspective and strongly percussive, it may be significant that her surname can be translated as ‘thunder,’ since it corresponds to the Chinese character that represents ‘Louie,’ meaning ‘rain on the field.’7

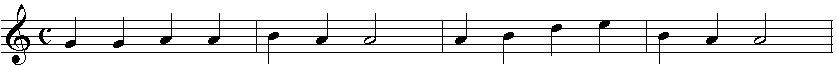

Asian rhythms are not necessarily complex. One of the rhythmic patterns common in Chinese music is that of continuous quarter and half notes. This simplicity can be seen in a passage from Louie’s Music for a Thousand Autumns,8 in which she states the first melody she learned on the ch’in – ‘Yearning on the River Shiang’ (Example 1).

Example 1: Music for a Thousand Autumns, 2nd mvt.

Such apparent simplicity, according to Marnix St. J. Wells, led to the misconception that rhythm was less important in Chinese music than melody, and that all Chinese music is in duple rhythm. It didn’t help that ancient Chinese writings ‘contain minute discussions of the mathematics of tuning, but scarcely a word about rhythm.’9 Subtleties of rhythm were not written down, but rather were transmitted from teacher to student. The first scores that do indicate rhythm, from the end of the sixteenth century, are ‘most often in free time with a beat coming only after the end of each verse-line, or with unequal numbers of beats per line.’10 So while some pieces (such as Louie’s solo ch’in melody) do have a straightforward duple beat, other pieces, especially those for ensemble, may have rhythms that seem irregular and complex by Western standards.

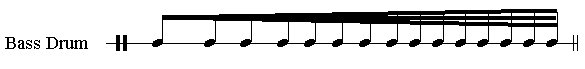

Garfias notes that in Asian music ‘changes in tempo are less often defined by change of pulse as by change in the number of beats to each accent.’11 This means that despite an unchanging pulse, the music may seem to speed up or slow down by the gradual addition or subtraction of notes. The same effect can be seen in Music for Heaven and Earth, at the point where Louie heralds the arrival of the Thunder Dragon (Ex. 2a, 2b):

Example 2a: Music for Heaven and Earth, 1st mvt., last bar of rehearsal no. 9: decelerando

This rhythmic complexity may also appear as sections that are senza misura. In gagaku, Japanese court music, ‘Tempo and rhythm are far from strict. Every piece begins waveringly, senza tempo, yet ends rather fast.’12 ‘At the last strong taiko (large drum) stroke the strict rhythm breaks and the solo instruments play in free tempo ... This is the standard performance format for all the Gagaku compositions.’13 Some of Louie’s compositions, such ‘Distant Memories’ the third of four pieces that make up the suite Music for Piano (1993),14 include sections that lack barlines, and Music for Heaven and Earth also includes passages in which some instruments perform senza misura but are accompanied by others that are barred.

Not only pulse but also percussion instruments lend a distinctive sound to most Asian ensemble music. Eta Harich-Schneider writes that the instrumental form of gagaku called togaku has three instrumental groups: 1) three high-pitched woodwinds; 2) three percussion instruments of contrasting pitch (side-drum, metal gong and big drum); 3) two low-pitched string instruments.15 The traditional orchestra for the Beijing Opera (an inspiration for Music for Heaven and Earth), consists of two main sections, percussion / non-percussion, the latter consisting of strings and winds. The percussion section includes clappers, a small, single-headed drum, a small gong, a large gong, and a pair of cymbals.16

While clappers produce a sound that resembles wood blocks, the predominance of bent pitches from gongs and cymbals would be less familiar to Western ears. As Louie writes in the forward to the score of Music for Heaven and Earth, ‘The listener might detect the use of some exotic instruments in the percussion section among which are to be found Chinese opera gongs (“bender gongs,”) and hand cymbals, Japanese temple bowls, a waterphone, a lion’s roar.’ This work also uses ‘kabuki blocks’ (clappers), a Chinese gong ‘about ten inches in diameter, not a bender gong,’ two water gongs, and an elephant bell, which is a metal bell suspended from a wooden frame meant to hang from a collar around the animal’s neck. All these instruments produce a sound that alters slightly or bends as much as a tone or more after the initial strike. (String and wind instruments are also required to produce glissandi.) Subtlety of inflection, then, is as important to Chinese music as it is to Chinese language.

The ‘lion’s roar,’ or string drum, one of the more dramatic bending instruments in Music for Heaven and Earth, is a drum with one end open and the other closed. The closed, upper surface has a central hole through which passes a length of cord or resined gut string, which is pulled up through the instrument to make a roaring sound. In Louie’s work it is played in the second movement as soon as the stage has been set for the arrival of the Thunder Dragon.

The temple bowls are reserved for the quiet third movement, titled ‘The Void.’ These are metal bowls whose inner rim is stroked in a circular pattern to create a continuous but subtly bending musical sound. Louie writes about the bowls in the score, ‘One must be large enough to have inside rim rubbed with a leather mallet. If unavailable, contact composer.’ The percussionist Gary Nagata, who studied with a master drummer in Japan, says of the temple bowls that

they don’t have a single pure tone. They have several overtones, so depending on how you’re listening you can hear a number of different sounds. They’re symbolic, too. They represent the fact that within one thing there are complexities.17Louie strove for even more dramatic pitch bending from additional instruments. The watergong is a tubular bell that is struck, then lowered into a tub of water to bend the pitch downward ‘to create a kind of Doppler effect.’18 If it is struck while in the water and then raised, the pitch bends upward.

The waterphone is a 20th-century instrument invented in the United States. It consists of a metal bowl containing water, with a domed lid that opens into a cylindrical tube. Around the edge of the dome are 25 to 35 nearly vertical tuned rods, which are to be played with mallets, sticks or a bow. ‘The use of water in the bowl produces timbre changes and glissandi.’19

Bent pitches were also a feature of Louie’s Distant Thunder (1992) for oboe and percussionist, a composition which calls for lowering a tubular bell into a basin of water and playing a cymbal laid on the head of a kettle drum while the percussionist shapes the pitch with the foot pedal to create a particularly eerie sound. Meanwhile, the oboist performs ‘a kind of sonic sorcery, her oboe transformed into a reed pipe, full of bent pitches and exotic flavours.’20

Jon Kimura Parker cites another example of an unusual combination of instruments that Louie uses to achieve bent tones. In Music for a Thousand Autumns, the initial attack on each beat is given by a vibraphone, and as this note dies away, a pizzicato-glissando on the contrabass is heard. ‘This combination of sonorities and “bent” pitches calls to mind oriental instrumental combinations and performance practise on them.’21

From the first bar of Music for Heaven and Earth, ‘Procession of Celestial Deities,’ the Asian rhythmic influence is obvious. The stroke of a bass drum is followed by kabuki blocks and elephant bell, and then later, after a passage in which the strings play bent tones senza misura, a fairly conventional Western-sounding brass fanfare leads to a rapid accelerando over one bar on the bass drum (see Example 2b), an exciting sound that is reminiscent of the Chinese New Year dragon parade and a more pronounced effect than the decelerando in Example 2a. This is followed by an accelerando passage which alternates the sound of a bender gong that bends upward and one that bends downward, soon accompanied by the jingle of Chinese hand cymbals. The movement concludes with the Chinese gong. The second movement, ‘Thunder Dragon,’ opens with the sound of kabuki blocks that accompany bending pitches in the flutes and oboes. The second measure brings a rapid accelerando to a ‘jet whistle blast’ accompanied by an upward bend from the bender gong.

Music for Heaven and Earth was commissioned by the Toronto Symphony. In the score, Louie writes ‘It offered me the opportunity to continue to explore the elements of my musical language (an integration of oriental musical concepts and Western art music) in a large orchestra context. Echoes of Gagaku music (Imperial court music of Japan) are heard in “Procession of Celestial Deities” [first movement] and elements of Peking opera summon the “Thunder Dragon”.’

Louie works hard to understand the possibilities of every instrument she encouters, talking to performers, asking them to produce certain effects, trying instruments herself and fine tuning her effects in rehearsal. She has said that when she was a student in Calfornia, Pauline Oliveros made her account for every note she wrote. It is in part it is this attention to detail, as well as a blending of eastern and western influences, that makes Louie’s compositions so richly rewarding, revealing greater depth with each exposure.

Kenneth DeWoskin writes that in early China, sages were often depicted with large ears. ‘Acute aural perception was of paramount importance in man’s perception of the world around him. The ability to distinguish and analyze sound was tantamount to the ability to distinguish and analyze all that was recurrent and intelligible in nature.’22

There may be a little of the Chinese sage in Louie, a perceptive listener whose music is not just something to listen to, but a journey into herself. ‘My music reflects who I am as a human being on this earth, and I am a strange mixture of East and West. When you mix East and West I think you come up with something very rich, and I’m very happy that I feel comfortable with that mix in my music.’23