The eight string quartets of R. Murray Schafer are unquestionably the most important contribution to the medium by a Canadian composer, and bear comparison with other major quartet cycles of the post-Bartók era.1 In November 2003 the Molinari Quartet of Montreal presented integral performances of the Schafer quartets in two concerts on one day (Nos. 1-4 in the afternoon concert, Nos. 5-8 in the evening) in five cities across Canada. The marathons began in Edmonton (Nov. 16), continued in Banff (Nov. 18), Montreal (Nov. 23), and Kitchener-Waterloo (Nov. 26), and ended in Toronto (New Music Concerts, Glenn Gould Studio, Nov. 30, with a large audience and the composer present).

Formed in 1997, the quartet is named after and takes inspiration from the Montreal painter Guido Molinari, and also rehearses in his studio. Molinari, as it happens, is Schafer’s exact contemporary (the two were born within three months of each other in 1933). The painter’s use of colour is reflected in the staging and apparel of the quartet. Four triangular shapes, each about 1.5 metres high and painted a different colour (green, yellow, blue, and red) were onstage behind the performers, and each musician wore black pants and a top that corresponded to one of these colours: red for the first violinist (fire), blue for the second violinist (water), yellow for the violist (air/light), and green for the cellist (earth/forest). This colour symbolism is explored in Schafer’s String Quartet No. 7.

Olga Ranzenhofer, the quartet’s first violinist, has been with the ensemble since its inception. She was previously the second violinist of the Morency Quartet, which also worked closely with Schafer. The excellent second violinist, Johannes Jansonius, joined the group in 1998, the cellist Julie Trudeau arrived in 2000, and the violist Jasmine Schnarr joined in 2002. The quartet specializes in the contemporary repertoire, and does not play anything written before 1900. It is difficult to make a full-time career out of quartet playing, and nearly impossible to do so by playing only the modern repertoire; the Kronos and Arditti quartets are notable exceptions to this rule. No doubt the Molinari would like to play quartets full-time, but for the moment, other individual commitments help to make ends meet and the group rehearses together for eight or nine hours each week and more intensively before a concert.2

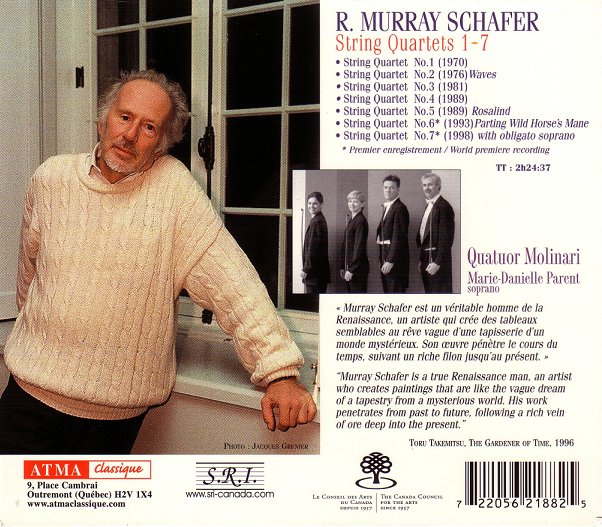

From the start, the Molinari Quartet has made a point of specializing in the works of Schafer. The group learned the first six string quartets in just two years and played them all in Montreal on 11 December 1999; on that same day it premiered the ‘stage version’ of the seventh quartet, which was written for it (it premiered the concert version of the seventh quartet in Ottawa on 4 May 1999). The eighth quartet (composed in 2000, revised in 2001) was also written for the ensemble. Between December 1999 and June 2002 the Molinari Quartet recorded all eight string quartets and also Schafer’s Theseus for string quartet and harp and his Beauty and the Beast for singer and string quartet.3

The Molinari Quartet follows in a distinguished line of Canadian ensembles that have performed the Schafer quartets. The first five quartets were written for the Purcell String Quartet of Vancouver (Nos. 1 [1970], 2 [1976], 4 [1989]) and the Orford String Quartet of Toronto (Nos. 3 [1981] and 5 [1989]) and both groups played the works regularly (the Orford played the first quartet over 100 times). Both groups made recordings of individual Schafer quartets, and the Orford Quartet recorded the first five works as a set in 1990.4 The violinist Andrew Dawes, first violinist of the Orford Quartet, also wrote about Schafer’s quartets (as has Ranzenhofer).5 With the disbanding of the Purcell and Orford quartets in 1991, the flame passed on to a new generation: the St. Lawrence, Penderecki, and Molinari quartets. These three groups collaborated on 2 August 2000 to present all the Schafer quartets in a concert for Festival Vancouver. Other Canadian quartets to feature Schafer in their repertoire include the Quatuor Arthur-LeBlanc (No. 4), the Borealis String Quartet (protégés of Andrew Dawes), the Diabelli String Quartet (No. 3, at the 2001 Banff string quartet competition), and the Lafayette Quartet.6 The St. Lawrence plays Nos. 3 and 6, the Penderecki performs Nos. 1, 4, and 5, but only the Molinari has the entire set of eight in its repertoire.

To hear the eight Schafer quartets performed in chronological order in a single day highlights the many connections between the individual works in the cycle. The first three works are strongly etched individual portraits; each explodes the string quartet medium and creates something new and striking from the shards. Nos. 4 to 6 and No. 8 do less violence to the medium (though they do stretch it in different ways), while No. 7 does more (indeed, it is hardly a string quartet at all).

One of the most memorable moments in the entire cycle is the opening of the first quartet. As one audience member remarked, it sounds ‘like the Indy 500.’ For four minutes the players snarl and writhe in dense tone clusters, as if enacting the violent death throws of the string quartet medium. The Molinari Quartet attacked this opening with flare and gusto, getting their cycle off to a memorable start. At the end of the first quartet there is a series of reminiscences of music that was heard earlier in the work, a gesture that foreshadows the organicism that later evolved between separate works in the cycle. In the first quartet (and indeed in all the quartets except the eighth) the players read from the full score rather than separate parts. It was mildly troubling to see that the members of the Molinari Quartet each seemed to be playing from a different taped together photocopied version. Evidently Schafer did not quite account for page turning needs in the final published version of the scores.

The second quartet, subtitled ‘Waves,’ forms the maximum possible contrast with the first. Anger gives way to meditation, artifice to nature. The two scores look similar at first glance, in that each uses a combination of traditional rhythmic values for short durations and proportional notation for anything longer than a quarter note. The phrase lengths and large-scale proportions of the second quartet, though, were guided by Schafer’s study of the ebb and flow of waves. The conclusion of the second quartet has to be experienced ‘live’ for the full effect, as the upper three players in turn get up and leave the stage, taking the music into the distance with them. The effect in the Glenn Gould Studio was enchanting, as the sound was stretched out to fill the studio from front to back by the departing performers. In the final moments of the quartet, the cellist is instructed to take up a spyglass and stare after the other players. In a note to the performers in the published score, Schafer writes ‘I am not absolutely convinced that the spyglass effect on the last page is vital to the composition’s effectiveness; and unless it is handled with great care it may even be inimical to it.’7 The Molinari’s cellist, Julie Trudeau, handled the effect with a quiet dignity and seriousness that had exactly the intended effect.

The third quartet begins with the cellist alone onstage, as at the end of the second quartet. The work opens with a very demanding solo which certainly taxed Trudeau’s abilities to the maximum. The spatial qualities of the third quartet in live performance are vital features of the opening and close of the work. In the first movement, the three absent players gradually converge on stage to join the cellist, and the work ends when all four are together. The Molinari performance of the third quartet was particularly riveting, as the maximum possible contrast was made between the second and third movements. The enthusiastic chanting of the vocables in the second movement underscored the vigorous physical energy of the performance. The end of the quartet was played with transcendent beauty, as Ranzenhofer slowly got up and left the stage, taking the simple but haunting music into the distance. Part of the charm of the conclusion of the work is that it is not entirely clear when it ends. The players hum and play simple melodic patterns over and over, the music gets softer and softer, and finally the audibility threshold is passed – the last notes are imagined rather than heard.

The fourth quartet begins as the third ended, with the first violinist offstage. The first three quartets seriously challenge received notions about the string quartet as a medium, but the fourth relies on purely musical argument. Ranzenhofer feels that Schafer achieved maturity as a string quartet composer with this work.8 It certainly bears the closest relationship of any of the eight works to the historical string quartet repertoire. In the final pages an offstage third violin and voice are added (presumably pre-recorded in the Molinari live performances). The third quartet certainly left hanging the question of how Schafer could further challenge the limitations of the medium, and the fourth quartet represents a decision to follow a different path from the one travelled in the first three works. String quartets with added voice have not been common, but there have been a fair number of examples ever since Schoenberg’s second quartet of 1907-08.9 The fact that Schafer uses only the syllable ‘ah’ for the voice part in his fourth quartet minimizes the disruption to the string quartet medium. Two features of the fourth quartet – the added voice and the use of pre-recorded music – are explored further in the seventh and eighth quartets. The fourth quartet brought the afternoon concert to an end and resulted in a well deserved standing ovation for both the quartet players and the composer.

The second concert in the Molinari marathon featured Schafer’s fifth through eighth quartets. In the fourth quartet the use of thematic material from the Patria series is subtle and was almost subconsciously arrived at, as the composer explains in his note in the published edition of the score.10 The fourth quartet is dedicated to the memory of bp Nichol, and makes use of a theme from Nichol’s role as the Presenter in the Prologue to the Patria series. Much of the fifth quartet is dominated by the Wolf motive from the Patria series, with its characteristic descending glissando. Another tie linking the fourth and fifth quartets is that the fifth quartet begins with the very theme for first violin that concludes the fourth. The Molinari performance of the fifth quartet was spellbinding, especially the conclusion with the use of struck and bowed crotales (played in turn by the violist and cellist), whose timbre blends perfectly with the artificial harmonics of the quartet. Crotales (small cymbals, tuned here to the pitches C and G) were used in ancient Egypt and Greece, and so it is fitting that in the fifth quartet they are used to accompany Ariadne’s theme from the Patria series.

The Sixth Quartet is the only one of the eight written for performers with whom Schafer did not enjoy a close working relationship. The premiere performance was given at the Scotia Festival in Halifax by the Gould Quartet.11 The work is subtitled ‘Parting Wild Horse’s Mane,’ which is the name of a Tai Chi exercise. The quartet takes its inspiration from this form of Chinese martial art, and is divided into 108 sections that correspond to the 108 movements that constitute a complete sequence of Tai Chi exercises. Of the eight quartets, the first and sixth are the only two which do not require additional musical forces or ask the players to leave the stage. The sixth quartet does allow, though, for the participation of a Tai Chi master, who performs the 108 exercises as the music is being played. This is an optional feature, and the Molinari decided not to include it in their concert.12 The music of this quartet is almost entirely derived from the first five quartets; the only new theme, labelled Tapio after the Forest Spirit of the Finnish Kalevala legends, is developed at greater length in the seventh quartet. The sixth quartet has a rather valedictory quality to it, as though Schafer wanted to revisit earlier ideas for one last time before finally abandoning the medium. To this listener, the musical results are not as compelling as in the earlier quartets; the quotations from the first quartet in particular seem overly intrusive in their new context.

The enthusiasm of the Molinari Quartet for his quartets rekindled Schafer’s interest in the medium and led to the creation of the two most recent works. The seventh quartet exists in concert and stage versions, and it is the latter that was presented by the Molinari. The stage version is more chamber opera than chamber music, with a prominent role for soprano, the use of costumes and lighting effects, and much perambulating by the musicians. A special sling was constructed for the cellist to allow her to walk and play at the same time (shades of Woody Allen’s film Take the Money and Run, in which he plays cello in a marching band). Trudeau’s rather cumbersome looking costume made her look like a moss-covered tree, complete with a cone-shaped hat that could be opened at the back to reveal a face (Tapio). The soprano (Marie-Danielle Parent, in fine voice), sang a series of four arias to texts collected in a psychiatric clinic from a schizophrenic woman.13 Parent wore a white straight-jacketed dress, emphasizing the relationship of this role to the Party Girl in Patria 2 (Schafer notes that in ancient China white symbolized death and funerals14). She engaged in histrionic altercations with the quartet, which led one reviewer to find the quartet ‘reminiscent of a goofy school play.’15 I certainly prefer the concert version of the work, but it was very courageous of the Molinari to tackle the theatrical version. I cannot imagine that there are many professional quartets who are willing to do it.

The eighth quartet, premiered by the Molinari Quartet on 1 March 2002 in Redpath Hall, Montreal, is in two movements (all the rest except No. 3 are in one). The first movement is related to Patria 8, which was written at the same time, and is based on a Chinese motive from that work. The second movement includes subtle use of a pre-recorded string quartet and makes use of the BACH motive. It is one of the highpoints of the entire cycle – solemn, complex, intense, and very moving, but never striving for effect. The Molinari performance was utterly gripping and resulted in the second standing ovation of the day. Their commitment to this music is unquestionable and their musicianship is compelling. What the Molinari Quartet now needs, and deserves, is a permanent residency at a leading music institution to allow them to devote their efforts to string quartet playing on a full-time basis.