Kevin Bazzana. Wondrous Strange: The Life and Art of Glenn Gould. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2003. 528 pp., ill. ISBN 0-7710-1101-6. $39.99 (cloth). Reviewed by Colin Eatock.

This latest addition to the ever-growing literature on Canada’s most celebrated musician, Wondrous Strange: the Life and Art of Glenn Gould by Kevin Bazzana, is lively and thoroughly readable. This ambitious book – its text is 490 pages in length – offers a painstakingly researched and highly detailed account of Gould’s life, from his birth in Toronto in 1932 to his death in the same city half a century later.

There are several previously published biographies of Gould: Otto Friedrich’s Glenn Gould: A Life and Variations (Toronto: Lester & Orpen Dennys, 1989) for instance, or Peter F. Ostwald’s Glenn Gould: The Ecstasy and Tragedy of Genius (New York: W.W. Norton, 1997). Bazzana, well aware he was walking a well-trodden path, chose a different approach. In his introductory comments he distances himself from those biographers who ‘saw Gould as an unclassifiable entity who came out of nowhere in 1955’ (p. 13), announcing his own intention to affirm Gould’s Canadian roots and identity. This decision, says Bazzana – a Canadian musicologist living on Vancouver Island – was motivated not by patriotism, but by a desire for ‘accuracy’ and ‘comprehensiveness.’ Bazzana has been true to his intentions, creating a biography that underscores his subject’s connections to his native country at every possible opportunity. Indeed, Wondrous Strange is perhaps more Canadian than its author consciously realizes – and this may account for both the strengths and weaknesses of the book.

The first two chapters are devoted to Gould’s formative years in and around Toronto. Bazzana also has much to say about Toronto itself, painting a portrait of a provincial city that was still loyal to King and Empire; where ‘Anglo-Protestant values were reflected in both public and private life’ (p. 17). Gould, we learn, grew up in a particularly British part of town – known simply as the Beach – where ‘Others’ were not welcome. As well, Bazzana provides some interesting information about the Gould (originally Gold) family’s roots in rural Ontario. Concerning the young Glenn’s parents, we are introduced to a respectable if somewhat remote father, and a doting mother with strong musical inclinations. Their frail ‘only child’ loved animals and the outdoors, disliked school, and took to the piano like a fish to water.

This is good writing: for Torontonians, Bazzana’s descriptions of civic life from the 1930s to the 1950s will ring true, and for those unfamiliar with the city, his account of the place is clear and informative. Moreover, he convincingly attributes Gould’s development to the values of his middle-class family, and also to a city whose musical culture was becoming increasingly sophisticated. There were many fine choirs and also a professional orchestra, and Toronto’s Massey Hall attracted such renowned pianists as Joseph Hofmann, Claudio Arrau, Robert Casadesus, Rudolf Serkin and Vladimir Horowitz. As well, there was the Toronto Conservatory of Music, where Gould studied under an excellent teacher, the Chilean pianist Alberto Guerrero, and there was the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, where the increasingly renowned Gould gave almost thirty radio recitals between 1950 and 1955. Bazzana makes his point well: Gould did not spring from a void.

In chronicling Gould’s years on the international concert circuit, from 1955 to 1964, Bazzana, of necessity, says much that has already been said elsewhere: most Gould enthusiasts already know about his performance of Brahms’s Piano Concerto in D minor with the New York Philharmonic, for instance, and Leonard Bernstein’s remarks that preceded it. Fortunately, Wondrous Strange brings some fresh insight to Gould’s decade on the road, including details of his 1957 tour to the Soviet Union, where he thrilled audiences with his performances – and shocked them with a lecture on twelve-tone music, which was then frowned upon in the USSR. Bazzana sheds a favourable light on the pianist’s decision, in 1964, to abandon the concert stage, presenting it as a beginning, rather than an ending. ‘Gould’s new life liberated him, and he began exploring new repertoire with relish,’ states our author (p. 244). He goes on to explain that Gould remained a very busy and productive artist, releasing 32 recordings in the first decade of his ‘retirement.’

This major shift in Gould’s career placed him squarely back in Toronto, and his post-concert career in his hometown occupies the second half of this book. We read of Gould’s copious writings on musical and philosophical subjects, his unique radio documentaries, his work in film and television, and his growing interest in conducting. Bazzana even hints that Gould might eventually have given up playing the piano altogether to pursue his other activities, had he lived much beyond 50. Again, this is all good stuff – but when Bazzana turns his attention to Gould as a man, Wondrous Strange becomes just plain strange. Addressing the controversial issues of Gould’s personality and personal life, Bazzana appears to present several contradictory arguments at the same time. This Canadian tendency to give equal weight to all sides of an argument can be a virtue – it has made Canadian soldiers the finest peacekeepers in the world – but here it clouds, rather than clarifies, our understanding of Gould.

Bazzana admits that Gould was ‘a queer duck’ – but he also asserts that he was in some respects ‘downright normal,’ dismissing as sensationalistic the idea that Gould was ‘a misanthropic, paranoid hermit, perhaps autistic or mentally ill’ (p. 316). Nevertheless, Bazzana goes on to discuss a number of traits that make Gould sound maladjusted, phobic and alarmingly withdrawn. His apartment was ‘heated to 80 degrees F, and his windows were permanently sealed against fresh air’ (p. 322). ‘His shirts and socks might be full of holes, pants split up the seat, shoes held intact by a rubber band’ (p. 324). ‘He would cancel a concert or an airplane flight if he believed it would turn out to be “unlucky”’ (p. 333). And ‘sometimes close friends of long standing found themselves suddenly shut out of Gould’s life, for reasons he would not share’ (p. 376).

Eccentricities? Perhaps, but it is harder to explain away Gould’s hypochondria. Reports Bazzana: ‘When an unavoidable emotional confrontation with another person loomed, he needed more than spinal resilience to deal with it; he needed Valium’ (p. 330). Gould also took prescription drugs such as Librax, Placidyl, Dalmane, Nembutal, Luminal, Aldomet, Indoral – the list goes on – and in 1976 was prescribed the anti-psychotic drug Stelazine. In fact, Gould seems to have had a mild psychotic episode in 1959: he imagined he was being spied upon and that people were communicating with him in code; and he rearranged his rooms because he did not like the way a piece of furniture was staring at him (p. 368-69). He had a small army of medical practitioners attending to his ailments, both imaginary and real, and he measured his own blood pressure several times a day. All of this surely exceeds any definition of eccentricity – there were, unfortunately, things wrong with Gould. Even Bazzana seems to grow unsure of his subject’s normalcy, noting that he ‘manifested a variety of obsessional, schizoid and narcissistic traits’ (p. 370).

Bazzana pointedly intertwines his discussion of Gould’s personal problems with accounts of his more admirable qualities. ‘He loved children all his life’ (p. 347) and ‘with the right people, he enjoyed nothing more than hanging around and shooting the breeze’ (p. 380) He also argues that, for a recluse, Gould knew a great many of people. Fair enough – but is Bazzana trying to say that Gould’s endearing characteristics somehow mitigated his more disturbing traits? Is not a hypochondriac who loves children still a hypochon-driac? In his efforts to be supremely even-handed, Bazzana’s message becomes confused.

There is one more disappointment that should not pass without mention. For reasons not entirely made clear, Bazzana declines to name names when writing about Gould’s love life – although he implies that he could if he wanted to. Other Gould biographers have taken a similar approach (one might almost call it a tradition), but it is hard to see what good purpose is served by such discretion twenty-one years after Gould’s death. It would have been far more useful for Bazzana to clear the matter up once and for all, so that Gould fans could at last move on to weightier issues.

Bazzana did not know Gould personally, as did others who have written about him, such as Geoffrey Payzant and John Roberts. And it is possibly for this reason that he felt the need to hedge his bets when describing his subject’s personality, quoting from many sources and balancing all assertions with counter-assertions. As an account of Glenn Gould’s origins, art and career, Wondrous Strange is a unified and purposeful contribution to the Gould literature. But as an account of Glenn Gould the man, it is a patchwork quilt of conflicting evidence, testimonials and opinions – interesting, but hardly a definitive statement on this brilliant, enigmatic artist.

Colin Eatock is a composer, writer (for Globe and Mail, Queen’s Quarterly, BBC Music, Opera), and a doctoral candidate in musicology at the University of Toronto.

Hommage à Marius Barbeau. Danielle Martineau, voix et direction artistique / voice and artistic direction; Lisan Hubert, André Marchand, Éric Beaudry, voix / voice; Lisa Ornstein, violon /violin; Daniel Roy, percussion, flûtes / flutes, guimbarde / jew’s harp, shruti, harmonica, dulcimer, voix / voice. Société Radio-Canada / Canadian Broadcasting Corporation TRCS 3004. Released in March 2003. $17.98. Reviewed by Gordon E. Smith.

Throughout his long career at the National Museum in Ottawa, his extensive fieldwork, and tireless efforts at promoting folk culture as a means of building a national Canadian consciousness through artistic production, Marius Barbeau (1883-1969) built a lasting reputation as a prodigious collector, commentator, and scholar on First Peoples’and Québécois culture. Within broad frames of social history and politics, Barbeau’s work may also be considered significant in shaping ideas associated with paradigms of nationalism and identity in twentieth-century Canadian contexts.

Hommage à Marius Barbeau is a compact disc recording of 28 songs originally recorded on Edison wax cylinders by Barbeau in the early years of his career (1915-20). Funded by the CBC and produced in 2003 in cooperation with the Barbeau Fonds at the Canadian Museum of Civilisation, the project was directed by the Quebec singer and folklorist, Danielle Martineau, and also includes vocal performances by Daniel Roy, Éric Beaudry, André Marchand, and varied instrumental accompaniments on violin (played by Lisa Ornstein), and whistles, shruti (drone), bombard, dulcimer, harmonica, tambourine, and rattle (played by Daniel Roy). Within a historical framework, Hommage à Marius Barbeau might be considered as a legacy in sound of Barbeau’s ethnographic work in his home province of Quebec.

In the liner notes to the recording, Martineau explains how she and each of the other performers were drawn to the study and performance of Quebec folk music. In addition, we are told about Barbeau’s extensive, indeed pioneering role, in recording, docu-menting, and thereby preserving traditional French-language songs in North America, the result of which is ‘a cultural treasure of great value.’ The performances on the compact disc have been reconstructed from listening to the wax cylinders, as well as studying available ‘scores.’ This process also involved finding out about the original informants from Barbeau’s documentation, and then attempting to balance the characters of the informants with those of the performers. Clearly, as indicated in the liner notes, and in the detail and care in the musical performances of the songs, Hommage à Marius Barbeau is a project of dedication and passion on the part of the participants.

In addition to the information about the performers, it would be interesting to know more about the reconstruction process in this recording project, including answers to questions, such as how valuable listening to the wax cylinders (with their known problematic sound quality) actually is, and what the criteria were for selecting the songs for the compact disc. For example, were some cylinders in better shape than others? Or, were there other reasons (i.e., thematic/ musical variety) behind the choice of the songs? And which collections were consulted? Certain sections in the notes suggest that Lawrence Nowry’s Man of Mana, Marius Barbeau: A Biography (Toronto: NC Press, 1995) served as a source (cf. Nowry’s account of Barbeau’s summer fieldtrip to Tadoussac in 1916, and his ‘discovery’ of Louis Simard ‘dit L'Aveugle’; pp. 150-52). In a perusal of Barbeau’s collections, I located a number of concordances between songs on the compact disc [indicated in square brackets] and transcriptions in Romancero du Canada (1936) [song 20], Le Rossignol y chante (1979) [15 and 22], En Roulant ma boule (1982) [6, 12, 26, 27], and Le Roi boit [19 and 23].

It would be helpful to have a listing of these concordances, as well as a more systematic way to track the titre critique of each song in Conrad Laforte’s Catalogue de la chanson française. From my own tracking of the songs to Laforte’s catalogue, at least ten on Hommage à Marius Barbeau are categorized as ‘chansons strophiques,’ four are ‘chansons en laisse,’ three are ‘chansons énumératives,’ and two are ‘chansons sur les timbres.’ The Laforte catalogue is a valuable research tool for searching song variants, as well as for explaining poetic distinctions in the song texts. Indeed, this kind of information can prove invaluable in reconstructing performances of the music. Along with providing the titres critiques for each song as Martineau has done here, I think it would be helpful if the scope and importance of Laforte’s catalogue were explained.

It would also be interesting to know about the musicians’ decisions related to performances of the songs. For example, how did the performers come to ‘select’ certain songs for their performance? Were voice quality and language pronunciation deliberately ‘matched’ to certain songs? Nonetheless, the overall result is a pleasing one, with the voices and instruments being combined to recreate ‘traditional’ performance contexts, combinations which are particularly effective in songs where there is a solo and a group [song 26], solo and instruments [many of the songs], and sung and spoken text [song 13]. The contrasting colour of the singers’ voices is also used effectively to portray the varied messages in the song texts (e.g., compare Lisan Hubert’s performance of ‘En revenant de l'Esse’ [song 11] and Danielle Martineau’s performance of ‘Quand le bonhomme revient du champ’ [song 19]; and Éric Beaudry’s performance of ‘J'ai la plus jolie maîtresse’ [song 5] and André Marchand’s performance of ‘Nous voilà tous à table’ [song 7].

A final comment concerns the repertory represented on this compact disc recording within the context of Barbeau’s work as a folklorist. Barbeau had strong beliefs about what constituted authentic folklore. As a ‘salvage ethnographer,’ there was an urgency about his work. Barbeau believed that the cultural essence of Canada could still be found on what he took to be the margins of modern life, in the case of his work in Quebec – elderly descendants of European settlers living in isolated rural communities. To this end, he was delighted to find informants such as Mme Jean ‘Français’ Bouchard, Louis Simard ‘L'Aveugle,’ and Édouard Hovington, each of whom is represented in songs on Hommage à Marius Barbeau. These prolific informants sang songs with qualities that confirmed to Barbeau their authenticity as folk songs: textual complexities and variety, and rhythmic, modal, and melodic qualities, all of which suggested a kind of artistic sophistication. A good example on Hommage à Marius Barbeau is Éric Beaudry’s moving performance of ‘La complainte du coureur du bois.’

Hommage à Marius Barbeau is a rare example of the revival of a folk music repertory through musical performances. It is to be hoped that it will serve as a starting point for further such projects. In many interesting ways, Hommage à Marius Barbeau reflects ideas and ideals of Marius Barbeau. Undoubtedly, he would be pleased. Gordon E. Smith

Gordon E. Smith is the director of the School of Music at Queen’s University. He is a co-editor (with Lynda Jessup and Andrew Nurse) of a forthcoming book titled Around and About Marius Barbeau: Writings on the Politics of Twentieth-Century Canadian Culture.

Beautiful: A Tribute to Gordon Lightfoot. Various artists. Borealis Recording Co. / NorthernBlues Music Inc. BCDNBM 500. Released September 2003. $24.25. Reviewed by Robin Elliott

Hard to believe, but this is the first tribute album for this great Canadian songwriter. Plans for the recording were already underway when Lightfoot experienced the serious illness in August 2002 that lent an extra urgency to the project. (Lightfoot is still recovering, but plans to release a new recording in 2004 and resume public appearances in 2005.) Most of the artists on this CD are Canadian, including Blue Rodeo, Bruce Cockburn, the Cowboy Junkies, James Keelaghan, and Murray McLauchlan. Fourteen songs by Lightfoot are covered, with one original song, ‘Lightfoot’ by Aengus Finnan. The liner booklet includes written tributes from the artists, but no lyrics. A standout performance is The Tragically Hip’s angry and raucous version of ‘Black Day in July,’ (they give the music a political edge that Lightfoot himself has always been rather reluctant to express), but all of the versions have something distinctive and attractive to say about the music.

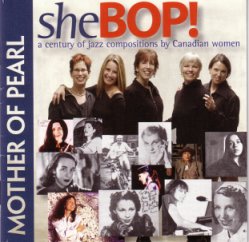

SheBOP: A Century of Jazz Compositions by Canadian Women. Mother of Pearl. Mopster Records MOP 02. Released March 2003. Internet: www.motherofpearljazz.com. $22.99. Reviewed by Robin Elliott

Mother of Pearl, an all-female jazz and blues quintet from Vancouver, began researching this project in 2000 and first presented it as a multi-media event (with over 100 slides) at Vancouver’s East Cultural Centre on 28 September 2001. The CD version of the project includes 12 songs by 12 different women, and ranges through ragtime, swing, Latin, bebop, fusion, and blues, taking in along the way a few songs that are not actually jazz in origin, such as ‘Les Policemen’ by the Quebec chansonnière La Bolduc, the Hockey Night in Canada theme song by Dolores Claman, and a couple of pop songs. The earliest song recorded here is ‘If You Only Knew’ (1921) by Montreal ragtime pianist Vera Guilaroff, and the most recent is ‘Look Ma, No Hands’ (1997) by Karen Young. Among the better known tracks are ‘I'll Never Smile Again’ by Ruth Lowe (a big hit for Frank Sinatra, and wonderfully sung here by the 83-year-old Canadian jazz veteran Eleanor Collins), ‘Blue Motel Room’ by Joni Mitchell (a torch song from her 1976 album Hejira), and ‘Bluebird on Your Windowsill’ by the Vancouver nurse Elizabeth Clarke (recorded by Bing Crosby and Doris Day, and familiar in more recent times from its use in the 1986 film My American Cousin). A handsomely produced 20-page booklet tells the story of each song, some of which have never been recorded before.

Contact information:

Institute for Canadian Music | Faculty of Music | University of Toronto | Edward Johnson Building

80 Queen's Park | Toronto, ON M5S 2C5 | Canada | Tel. (416) 946 8622 | Fax (416) 946 3353

Email: ChalmersChair@yahoo.ca | Web: www.utoronto.ca/icm