Lustre-ware Ceramics

High art and high tech from the medieval Middle East

Lustre-wares represent the highest expressions of ceramic art and technology in the lands of the Middle East from about AD 800-1300. Lustre pigment is a compound of silver and copper in a refractory earth medium, applied to the glazed surface of a previously fired vessel. The painted object is then refired to a red heat in a reducing atmosphere in a small specially constructed kiln used only for this purpose. In the second "firing" the metals are bonded to the glaze as a thin layer with a strongly metallic lustre, the refractory earths can then be brushed off. This is considered to be a complex and specialized process, which was probably also kept secret.

Research on these wares at the ROM has taken three approaches. Firstly, they have been subjected to petrographic analysis in order to determine the place of manufacture. Secondly, a chronological sequence for the ceramics was developed using traditional archaeological approaches, such as using pottery drawings, but applied to all the available material from whatever source. Thirdly, the methods of manufacture were determined using a scanning electron microscope with attached analytical facilities.

Lustre-painted ceramics were first produced in Basra, Iraq in about AD 800. Basra was one of the foremost production centres in the world at this time, exporting its wares to the furthest extent of the Old World. Many technological advances were undertaken at Basra, including not only lustre-painting itself but also painting in cobalt-blue and adding tin to the glaze to make it opaque. In about AD 975 the potters appear to have left Basra, and started production at Fustat, or Old Cairo, in Egypt. The lustre potters also developed new technologies here, in particular they invented stonepaste, a new type of ceramic body made up of about 8-10 parts of crushed quartz, one part of clay and one part of glass. There were several advantages to making this body. One is that it is always predictable, even if a potter moved into a new area, the properties during firing of stonepaste would probably be pretty much the same, whereas clay-bodies may change radically. This is especially important for these potters as their glazes and decoration needed very specific firing conditions.

Although lustre-wares would continue to be made in Egypt until about AD 1175, in about AD 1075 many appear to have left to make pottery in Syria and Spain. A number of production centres eventually developed in Syria, the earliest is at an unknown location, but later lustre-wares were made at sites like Raqqa in eastern Syria and at Damascus. Apart from making lustre-wares, these potters also developed a new ceramic technology, which we call underglaze-painting. In this an oxide pigment, such as chromium for black, cobalt for blue, and iron for red, is applied to the surface of the vessel, which is then covered with a glaze that has an alkali flux.

About AD 1100 something happened to the site of the first lustre-ware production centre in Syria, where they were making a style of lustre-ware often known as "Tell Minis" ware. As a result, the lustre-potters moved to other sites in Syria, and also to Kashan, in Iran. From about 1100 to about 1340 we see the ceramics at Kashan assuming a position as equal to any other art in this or any other part of the world.

This research has been funded in part by grants from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and the Royal Ontario Museum .

Location of lustre-ware production sites in Egypt, Syria, Iraq and Iran

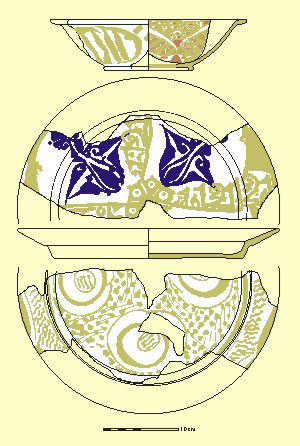

Lustre-painted pottery from Basra, Iraq. Upper of 9th century

AD with polychrome lustre, lower of 10th century AD with

monochrome lustre and cobalt-blue paint

Bowl, lustre-ware, "Tell Minis" style, Syria, about AD 1075-1100. Diameter: 19.8 cm. ROM 960.219.2 (photo courtesy W. Pratt)

Bowl, lustre-ware, Kashan, Iran, about AD 1260-1280. Diameter: 19.1 cm. ROM 972.339 (photo courtesy W. Pratt)

|