Walter Pitman. Louis Applebaum: A Passion for Culture. Toronto: The Dundurn Group, 2002. 512 pp., illus. ISBN 1-55002-398-5. $39.99 (cloth). Reviewed by John Beckwith.

The acronyms NFB, CBC, CLC, OAC, FCPRC and SOCAN partly summarize the centres of influence of the composer Louis Applebaum (1918-2000) to which SSF could be added, if the Stratford Shakespearean Festival ever used a short form. He was an inspired idea man, a constant champion of artistic creativity whose trademark attitude in meetings was ‘let’s get on with it’.

The new biography by Walter Pitman, a fellow arts mandarin, benefits from interviews with Applebaum during his last years, and with numerous other associates. It covers in careful detail the cultural ventures and struggles in which Applebaum played an often-central role - the National Film Board, CBC Television, and the Canadian League of Composers in the 1950s, the Stratford music programs in the 1960s, the Ontario Arts Council in the 1970s, the Federal Cultural Policy Review Committee in the 1980s, the merging of ProCan and CAPAC as SOCAN in the 1990s. In tracing the ups and downs of these involvements, Pitman is sometimes over-careful and over-detailed, making his work longer and denser than would seem appropriate, more like a series of minutes than a readable biography: one imagines Applebaum calling out, ‘let s get on with it.’

Chapter 18 is headed by a quote from Applebaum: ‘I want to be remembered as a composer.’ However, this chapter, with its 25 pages, measured against 45 for the two-chapter account of the FCPRC, falls short of fulfilling his wish. Aside from general notes of approval (‘two fine compositions,’ ‘another fine piece’), the chapter consists of a résumé of works’ titles and circumstances of their writing, with brief quotations from newspaper criticisms. There are no musical examples. Surprisingly, the volume contains no works-list and no discography by which readers could be led to explore Applebaum’s music.

Thus inspirations such as the sound of the shofar in his King Lear music, the setting of ‘Hark, hark, the lark’ in the style of Cole Porter, the passacaglia in The Harper of the Stones, go unmentioned. Applebaum’s compositional skill and facility were enviable. He once told me it usually took him twenty minutes to complete a page of orchestral scoring. When I asked how he did that, he replied, ‘I just never change my mind.’ Pitman recounts (p. 367) that Applebaum was once asked how long it took him to write a Stratford background score. He said with a wink, ‘it takes a few hours ... but say a couple of weeks’ – i.e. for publication, the latter, exaggerated, answer would be more impressive. In music, too, he liked to ‘get on with it.’

A list of small errors, including misspelt names, wrong identifications of individuals in the text (and several times in the photo captions), and incorrect locations and dates, comes to over two dozen items - surely a sign of inadequate copy-editing and proofing. The extended opening paragraph of Chapter 1 sets the scene of Applebaum’s birth-year, the final year of ‘that horrendous struggle,’ World War I. Similar social or historical backgrounds occupy inordinate space in later chapters, often with similar clichés (Chapter 16: ‘the vitriolic fury of Canadians at the Liberal Government’s lack of action in the face of economic turmoil...’). The notes and index make up twenty per cent of the book, the latter in almost unreadable small type. The notes were evidently motivated partly by the need to acknowledge sources and partly by the questionable need for even more backgound (e.g., note 5 on page 485 takes up two-thirds of a page).

Louis Applebaum , gifted creator, compelling personality, and one of the great musical movers and shakers of Canadian life in recent times, deserved better. John Beckwith

Michael Barclay, Ian A.D. Jack, and Jason Schneider. Have Not Been the Same: The CanRock Renaissance, 1985-1995. Toronto: ECW Press, 2001. xii, 757 pp., ill. ISBN 1-55022-475-1. $29.95 (paper). Reviewed by Andrew M. Zinck.

Amid the vast desert of literature on Canadian music (both classical and popular), an oasis, large or small, is a welcome sight. The appearance of an in-depth examination (over 700 pages) of a mere decade of the alternative/punk music scene in Canada promises to quench the thirst of many a reader of Canadian cultural history. In Have Not Been the Same, Michael Barclay, Ian Jack, and Jason Schneider collaborate to explore the explosive growth of Canadian rock music that occurred between 1985 and 1995, ten eventful years that witnessed a major transformation in the way that Canadian musicians felt about themselves, their national identity and their ability to create music with a distinctive voice. The three authors (music journalists and musicians themselves) piece together a rich mosaic of engaging stories drawn primarily from interviews with Canadian musicians, producers, and club owners.

Barclay, Jack, and Schneider highlight a number of factors that contributed to the so-called 'CanRock Renaissance.' They cite the blandness of mainstream music in the 1980s as a catalyst that led many to explore more engaging musical experiences. This, combined with the strong 'do-it-yourself' attitude common in the alternative music scene, fostered a subculture defined by bands determined to perform and record their own distinctive brand of music, bypassing established venues that were provided (and restricted) by the corporate music world. These musicians found regional outlets for their creative expression through the campus radio stations that began to appear across the country, and many eventually achieved national exposure on two CBC late-night shows, Brave New Waves and Nightlines. The counter-cultural energy of MuchMusic in its early years, combined with the force of the CRTC’s Canadian content regulations, provided additional exposure for many young artists through the broadcasting of their music videos.

The authors describe with fine detail the uneasy tension that has existed between mainstream rock/pop and the alternative/punk scene in this country. Every chapter exudes sympathy for the struggles of the young artists, enthusiastically charting their successes and disappointments as they toiled in relative obscurity on the fringes of the music industry. The result is a vivid portrait of a subculture that has received little attention (critical or otherwise) in this country.

The opening two chapters provide the strongest moments in the book, painting a stark picture of the cultural climate that gave birth to the 'CanRock Renaissance.' The remaining fifteen chapters present thematic collections of narratives (illustrated with numerous photographs) that focus on such bands as The Rheostatics, Skinny Puppy, Spirit of the West, Sloan, The Tragically Hip, and Blue Rodeo; regional music scenes in Montreal, Vancouver, and Halifax; and the emergence of a number of independent record labels. Occasionally, developments are presented in the context of events in the United States at the time, contrasting the cultural and economic climates of the two countries and demonstrating how a number of Canadian alternative bands actually anticipated similar developments in the United States. Although the authors tend to avoid mainstream and established artists, they do describe the influential roles some of them played in fostering the development of distinctive Canadian musical voices among the younger crowd. The authors also highlight the challenges of the 'cultural baggage' that many Canadian rock musicians had to address; for a number of bands in the late 1980s, success involved coming to terms with cultural identity issues raised by the successes of their musical predecessors of the 1960s and 1970s.

Early in the book, the authors reveal their scorn for mainstream rock and pop music in North America, condemning it as a vacuous artistic movement and as a negative, hegemonic cultural and economic force. While the sympathy expressed toward the alternative subculture(s) helps them to present a compelling case for understanding the importance of the alternative/punk movement in this country, it leads to the frequent dismissal of positive contributions from the mainstream music industry. In terms of corporate elements, the authors tend to consider valuable and positive only those activities that are themselves subversive and anti-establishment-oriented, taking place in obscure, darkened corners of various corporate empires.

One of the challenges of presenting any subject as painstakingly as the authors do here is to maintain a sense of direction and unity. After the initial two chapters, the narrative leads the reader through myriad winding paths and alleys that often cross many times, with no clear road map. At times, amidst the many shining gems of personal accounts of artistic struggle and success, the overall point the authors are trying to make is forgotten. For readers interested primarily in the many first-hand accounts of particular events, this might not be a problem, but the overall focus is clearly weakened by the approach.

The accompanying annotated bibliography is extensive and is organized according to chapter, with over 900 recordings listed. Unfortunately, the annotations are uneven in quality; while many entries include detailed comments that explain the content and significance of the recordings, others are terse and cryptic, requiring a degree of familiarity with the materials that many readers will likely not possess. Since the authors make a point of explaining how so many Canadian alternative bands have toiled in obscurity, the bibliography represents a lost opportunity to share valuable insights about these recordings with a readership that would likely be interested in exploring the actual music that is discussed within the pages of the book.

Despite its shortcomings, this book is still a valuable contribution to Canadian popular music literature. While it does reveal clear biases in terms of the artists who receive coverage, the authors are upfront about the reasons for their choices, and the issue of bias fades to the background when the larger message of the book is considered. Collectively, the stories of these musicians demonstrate how a new generation of confident, talented artists succeeded in energizing the music scene in Canada for over a decade through their determination and inspired leadership. Andrew M. Zinck

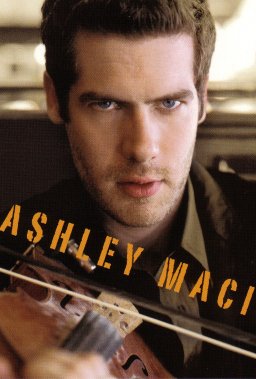

Ashley MacIsaac. Decca Records CD 4400189212, recorded in 2002 and released in March 2003. $12.99. Web: http://www.ashley-macisaac.com.

In many different cultures stories exist, in literature and legend, about the devil, death, and the violin. Tartini's Devil's Trill sonata, Paganini's pact with satan, C.F. Ramuz and Stravinsky's L'Histoire du soldat, the Quebec folk tale of the Hangman's Reel (Reel du pendu), François Girard's film The Red Violin - all are variations on a common theme: the violinist (or violin) whose powers are so amazing that they can only be explained by recourse to myth. Devilishly talented and devil-may-care Ashley MacIsaac is the present-day incarnation of the type of violinist that gave rise to such stories.

The photo of MacIsaac on the cover of the booklet for his most recent CD (see left) already provides evidence of this. His piercing gaze is more than a little reminiscent of the work by an anonymous British artist titled Death Plays the Violin (see right). Except, of course, for the fact that MacIsaac plays the violin backwards: he holds the instrument with his right hand and bows with his left. In the world of classical violin performance this is exceedingly rare, due to the visual disruption caused when one violinist is bowing in the opposite direction to the rest in an orchestral setting. In addition, left-handed violins, with the strings reversed and internal components built in the mirror image, are rare and, needless to say, none of the greatest luthiers made any. In the majority of cases, left-handed classical violinists play this way due to an injury to their left hand, as was the case with Rudolf Kolisch, for instance. Left-handed playing is less rare among fiddlers, but it is still enough of an exception to brand MacIsaac as unconventional.

But left-handedness is one of MacIsaac's lesser unorthodoxies. At 28 years of age, he already has a long and vivid history of controversy in his past, most of it given wide publicity in the media. Fiddling with Disaster, the title of his autobiography (which is due out next month), sums the matter up nicely. In this regard, MacIsaac follows in a long line of musicians persecuted for their private life. He is granted a degree of latitude in such matters by the media; indeed, his frank comments about his sex life and drug use have often made for 'good press' in the past. But the media exposure was a double-edged sword: it created and sustained his celebrity for a while, but then turned against him when his actions became too unorthodox for the general public.

Erna MacLeod has written about MacIsaac's troubled relationship with the media in a recent article that has something of the tone of an obituary for his career.1 It is certainly too soon to declare MacIsaac finished. His 1995 major label debut, hi how are you today?, sold some 350,000 copies. That is an impressive figure for a fiddle recording, but small beer in the pop music world to which MacIsaac so obviously aspires. Fiddlers just don't make the top-40 play list, and so in addition to playing violin throughout this CD, MacIsaac sings on six tracks. His is not a great voice; he should leave the singing to Mary Jane Lamond, whose Gaelic vocals for 'Sleepy Maggie' were a highpoint on hi how are you today?. Lamond is heard here in one of the best songs, 'To America We Go,' which she co-wrote with Roger Greenawalt, who also produced and performs on the recording. Purists might find the drum beats and electric bass lines too heavy on many tracks, but lovers of sensational violin playing will find much to delight in. MacIsaac's return is most welcome. Robin Elliott

Contact information:

Institute for Canadian Music | Faculty of Music | University of Toronto | Edward Johnson Building

80 Queen's Park | Toronto, ON M5S 2C5 | Canada | Tel. (416) 946 8622 | Fax (416) 946 3353

Email: ChalmersChair@yahoo.ca | Web: www.utoronto.ca/icm