|

|

|

|

*** See all

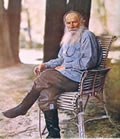

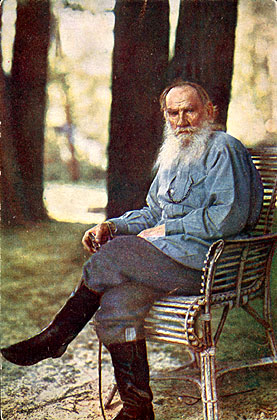

the photographs Prokudin-Gorsky took at Yasnaya Polyana in May of

1908. *** In 1908, Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorsky, a Russian scientist, inventor, and entrepreneur, sent the following letter to L. N. Tolstoy: 23 March

1908

I recently developed a colored photographic plate someone (whose name I don't recall) took of you. The result was very poor -- it was apparently done by someone unfamiliar with the process. Photography "in natural colors" is my specialty and you might know my name from the press. After many years of work, I have now achieved excellent results in producing accurate colors. My colored projections are known in both Europe and in Russia. Now that my method of photography requires no more than 1 to 3 seconds, I will allow myself to ask your permission to visit for one or two days (keeping in mind the state of your health and weather) in order to take several color photographs of you and your spouse. The finest nuances of color are completely and correctly conveyed. ... My work is a result of studying the properties of silver bromide. To me it seems that photographing you in the full, accurate color in your natural surroundings would render a service to entire world. These images are eternal - they do not change. No other color process can achieve such results. Lev Nikolayevich, if you are willing to provide this great service not only to me, but also to your innumerable admirers, then you will permit me to arrive sometime before April 2, since on April 5 I must leave for the chemical congress in London. If this is impossible, then perhaps I could arrive during the first half of June. As I already mentioned, I only need from 1 to 3 seconds to take the photograph, and therefore this not will be overly tiresome for you.

Prokudin-Gorsky received his requested invitation and spent two days (May 22-23, 1908, OS) at Yasnaya Polyana. A few days later, he sent the following letter to Tolstoy: May 27, 1908.

It is only today that

I returned home, having been detained in Moscow at N. S. Bakunina's

place. I recall with great pleasure the two days I spent with you at

Yasnaya Polyana. Many thanks to you - everyone at your place is so kind.

The final portrait, taken in color (using the large camera), came out

excellently, and I will strive to send a copy to you soon. Today I enclose

for you the photographic periodical which I publish, and although you

likely will have no time to look into it, it is pleasant to think that

it will be in your home. Moreover, inside you'll find many pictures

produced in my workshops from my photographs - possibly, when you have

a chance, take a look. I also enclose some color postcards produced

from my negatives. Not all are completely successful, but there are

some that aren't bad. It's very pleasant to

show you my work, since I am confident that you will take joy in my

successes. For ten years, above and beyond the purely scientific realm of photochemistry, I have been working on the organization of establishment of color photography in Russia. Until now everything has been done exclusively abroad, and now we, too, are making advances. It was especially difficult inasmuch as I am the only Russian who works in this the field, and all measures were taken to stifle my advances, but they did not succeed. In a week or so I will send you something in color that I took at Yasnaya Polyana. I apologize for having talked your ear off and taken up all your time… Sometimes I shut my eyes and see what happens at Yasnaya Polyana. Probably at the end of

June I'll need to see to some business around Tula, and I will request

your permission, to drop by and see you, albeit for a few hours. I heartily wish you health

and all the best.

P.S. I won't be bringing any huge photographic equipment along with me, of course. A few months later, in its August 1908 issue, The Proceedings of the Russian Technical Society ran the following announcement describing "the first Russian color photoportrait," a color photograph of L. N. Tolstoy: "On the day of Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy's birthday, the entire Russian press greets the great writer of the Russian land, devoting to him articles, recollections, and testimonies regarding his literary activity... Our periodical, as a purely technical one, cannot honor this venerable representative of Russian thought and word with special articles. Desiring, however, to take part in the general festivities, the editorial staff of The Proceedings of the Russian Technical Society decided to publish in this, its August issue, the newest portrait of Tolstoy, which is the dernier mot in photographic technology. The portrait was taken on location and in natural colors, achieved through technical methods alone, without any use of the artist's brush or tool. The portrait is all the more appropriate on this festive day inasmuch as it celebrates Russian technology. Only because of technical improvements in the color sensitivity and accuracy of color transfer perfected in Russia by S. M. Prokudin-Gorsky is such a portrait possible. The portrait is produced by a photomechanical method: it was printed on the page by a typographical machine in three colors using three different color plates. The nuances of colors and even grey were produced from the combination of blue, red and yellow dyes - each from its corresponding color plate, testifying to the faithfulness of the analysis of colored rays and synthesis of pigments." Prokudin-Gorsky had written a different caption for the photograph, which, for unknown reasons, was not used. It was later found in a state archive in Leningrad, and published for the first time in 1970 by S. Garanina: Included in the present issue is a portrait of Count L. N. Tolstoy, which was made by me on May 23 of this year [1908] . It is the first and only color portrait made directly "d'après nature" [с натуры]. In spite of some unfavorable conditions for photographing (due to the hurricane in May) which forced me to increase considerably the exposure time, I nevertheless had to limit myself to an exposure time of only six seconds, which includes the time required for the movement [of the glass photographic plate] through the very large cassette. The shot was done one time, and I personally carried the cassette to Moscow, where it was only possible to remove the plates and pack them. The developing of the plates took place in Petersburg. This extremely difficult work could be executed with such a short exposure time solely because of the extraordinary sensitivity of my plates to light rays and their correct transfer, which anyone will understand who is familiar with the technology of colored reproductions. The thought to take a large-format portrait of Tolstoy occurred to me completely by chance, and it was undertaken more because my friends insisted on it than on my personal initiative. The fact is that I had long meant to request permission from Tolstoy to take his portrait in order to demonstrate my color photography. My written request was sent in the beginning of May [this date is at odds with the information from above, which indicates that Prokudin-Gorsky sent the request at the end of March 1908] , and I received Tolstoy's friendly agreement. Before my departure, many of my acquaintances, having learning that I was taking with me only a small camera, persuaded me to take something more substantial in size so that subsequently it would be possible to prepare a large-scale portrait and to print it for general use. In spite of the significant unwieldiness of the device and great technical difficulties, I decided to attempt this experiment and, in the middle of May, I left for Yasnaya Polyana. Tolstoy was very friendly and, in spite of very little free time, he conversed with me several hours during my three-day stay [actually two days] at Yasnaya Polyana. He was particularly interested in all newest discoveries in different scientific realms, and likewise interested in the photographic reproduction of images in verisimilitudinous colors. Tolstoy's comparatively poor health, his advanced age, his constant work, and his various visitors did not allow me to do any preliminary experimental shots, so it was necessary to rely mainly on my extensive experience and the sensitivity of plates. Given the extremely unfavorable location for photographing, the photograph was shot in the garden, in the shadow that is cast from the house. The sun was brightly shining in the background. The photograph was taken at 5:30 in the evening, immediately after Tolstoy had returned from horseback riding. Sofiya Andreyevna, Lev Nikolayevich's wife, did her best to contribute to the success of this work, for which I offer my sincere thanks to her. The print of the portrait is produced without any corrections and colorings, thereby preserving the complete authenticity of the reproduction. S. Prokudin-Gorsky

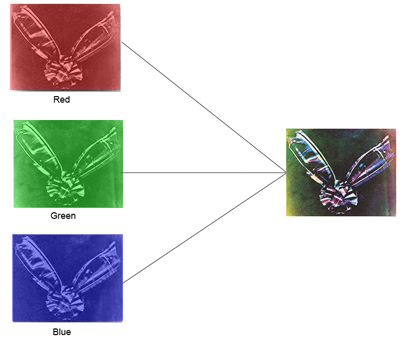

(1) See all the photographs Prokudin-Gorsky took at Yasnaya Polyana in May of 1908. Prokudin-Gorsky and the History of Color Photography Almost from the invention of photography in the late 1830s, photographers collaborated with artists to produce hand-tinted color photographs and, later, in the 1880s, to create photochromes, color lithographs made from black-and-white photographic negatives. True color photography was first demonstrated in 1861, when Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell produced the first color photograph using a process very similar to the one Prokudin-Gorsky would later perfect: Three black-and-white (more specifically, halftone) photographic slides were taken in succession of a tartan ribbon. Each photograph was taken through a different color filter: red, blue, and green. This process produced three photographs that represented the spectrum in various shades of grey (lighter hues were lighter grey, darker hues were darker grey). Maxwell then projected the three slides using three different projectors, each affixed with the same color filter that had been used to produce the slide. Since the entire light spectrum is made up of mixtures of these three primary colors of light -- red and green together make yellow, red and blue make magenta, and blue and green make cyan -- the three primary-color images, when perfectly aligned, produced the first color photographic image:

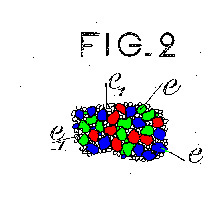

(Maxwell's tartan ribbon, with my elaborations. In fact, Maxwell also shot and projected a yellow image in addition to the three above. Why he used the extra filter is unclear, but its likely purpose was to decrease the action of the blue rays, since photographic film was particularly sensitive to blue at the time.) By the end of the nineteenth century, chemists and inventors, notably Frederic E. Ives and Adolf Miethe, had improved upon Maxwell's experiments. In the early 1890s Ives was manufacturing a reliable trichromatic camera (called variously the Chromoscope, Kromoscope, or Kromskope Triple Camera) which produced a "kromogram." A specialized viewer or a projector was used to view the images. The trichromatic projection process was not, however, the only way to produce a color photographic image. In 1904, the Lumière Brothers developed the first practical commercial color photography process that resulted in a single, full-color image, using a single photographic plate called the Autochrome. The process was ingenious: They began by coating a glass plate with an evenly dispersed emulsion containing microscopic translucent starch grains dyed the colors of the primary colors of light: red, green, and blue (about five million particles per square inch).

To finish, the Lumières then applied a layer of gel containing an orthochromatic (color responsive) emulsion of silver bromide and a layer of varnish.

That is to say that chemical record was made on the light-sensitive emulsion that corresponds to the color and intensity of the image being photographed. Since silver bromide produces a negative of an image, once the image was initially developed (without being fixed), what resulted was a complementary color image. To produce the final, positive color image, the photographer developed the slide again. To view the photographic plate, one could project it through a magic lantern or simply hold it up to the light. Autochromes are unique inasmuch as the negative and positive are developed on the same glass plate, the dyed starch granules providing the color and the silver bromide controlling the hue.

(The image produced on an Autochrome was soft and subtle, almost like an Impressionist watercolor. Since close inspection would reveal the pattern of primary-color particles, the effect was not unlike pointillism. One reason for the immediate popularity of the Autochrome was that it was based on glass plates that fit in most cameras.) Given its market prevalance, the failed photograph that Prokudin-Gorsky mentions in his letter to Tolstoy was likely taken using the Lumières' Autochrome. Although the Lumière glass plates were widely in use when he took the above picture of Tolstoy, Prokudin-Gorsky used a camera that worked along the lines of Maxwell's tricolor process. Apparently using a camera of his own design (though it was based on existing cameras invented by Miethe and Ives), Prokudin-Gorsky took three black and white photographs in rapid succession by means of a geared, spring motor that pulled a cassette loaded with a rectangular plate glass negative through three successive exposures opposite color filters. (He mentions this process above in his unpublished preface to Tolstoy's photoportrait.)

(The Miethe-Bermpohl Dreifarbenkamera ("Three Color Camera"), designed by Adolph Miethe and produced beginning in 1899, when Prokudin-Gorsky was still studying with Miethe in Berlin.) Miethe's camera (above) was known as a "one shot" because it could simultaneously make three color-separation exposures by using a prism and mirrors to split the light. From the unpublished preface to Tolstoy's portrait and from his letter to Tolstoy, it is clear that Prokudin-Gorsky used a different, larger, gear-driven camera at Yasnaya Polyana ("the big camera"). The one-shot camera could produce only small-format slides, greatly limiting ultimate projection and printing size. Perhaps Miethe's one-shot camera was "the small camera" that Prokudin-Gorsky refers to. It is also possible that "the small camera" was used to take Autochrome slides, since Garanina reports that there are extant color glass slides of Yasnaya Polyana, taken by Prokudin-Gorsky in May of 1908. Equipment aside, Prokudin-Gorsky's aim was to produce three negatives: one that captured only the blue tones, one that captured the red, and one that captured the green. Prokudin-Gorsky developed the glass negative onto another glass plate, producing a black-and-white positive slide like the one below (taken May 23, 1908 at Yasnaya Polyana):

To produce a color image, Prokudin-Gorsky used a specialized projector, fitted with the appropriate color filters between the image and a lens.

By carefully aligning the three projections, he could project a full-color image like the one below onto a screen:

(I used Photoshop to assign color channels to each of the three black-and-white images of Yasnaya Polyana above, then registered them. The streaks of color result from degradation in the emulsion. See here for all the photographs Prokudin-Gorsky took at Yasnaya Polyana.) In his letters and scientific writings, Prokudin-Gorsky is at pains to insist on the objective nature of his color transfer ("natural color" "no artist's brush," "accurate, verisimilitudinous colors", etc.). Many factors, however, remained very subjective and under his direct control during the development and projection process. He undoubtedly manipulated his slideshow images to produce the "most real" colors. According to the archivist at the Library of Congress, most of the original glass negatives taken at Yasnaya Polyana -- including two portraits of Tolstoy and one of Sofiya Andreevna -- have been lost. (See here for all the photographs Prokudin-Gorsky took at Yasnaya Polyana). Still extant are black-and-white composite prints made from the glass negatives. Although Prokudin-Gorsky had no way to create color photographs as we now conceive them -- that would have to wait until around 1930, when Kodachrome film was invented -- he could produce color images using the "photomechanical" method mentioned in the note from the editors of The Proceedings of the Russian Technical Society. (Prokudin-Gorsky's father-in-law, A. S. Lavrov, a St. Petersburg industrialist, was active in the the Society, which likely explains how the picture came to be first printed in the Proceedings.) This process produced a lithographic print using a high-speed cylinder printing press and oil-based ink. The three halftone photographs must have been translated into screened color separations for printing using blue, red, and yellow inks (they started out as blue, green, and red), as the editors of The Proceedings indicate in their introduction to the print. The postcards and magazines that Prokudin-Gorsky sent Tolstoy in May 1908 must have been printed in this manner. In addition to the original

reproduction in The Proceedings of the Russian Technical Society,

Prokudin-Gorsky later published the color print of his photograph of

Tolstoy in a magazine which he published, Amateur Photographer

(Фотограф-Любитель

How accurately a lithographed reproduction like the one above of Tolstoy represents the "real" colors of Prokudin-Gorsky's original projected image is debatable: Lithographs use the subtractive color process, the combination of colored inks to create the impression of the color spectrum. Prokudin-Gorsky's projected photographs, however, relied on additive color, the combination of colored lights, precisely like the modern television or computer monitor. Inevitably, the photomechanical version is untrue to the original black-and-white glass slides. Prokudin-Gorsky earned no small renown and money from the photographs of Tolstoy. He parlayed this fame into commission from the Tsar to spend six years (1909-1915) photographing the vast Russian Empire "in natural colors." After the Revolution, Prokudin-Gorsky fled, somehow managing to take with him his equipment and all his slides, which were purchased in 1949 by the Library of Congress. In 2003, the Library mounted an exhibition of Prokudin-Gorsky's photographs, "The Empire that Was Russia," including about 100 colorized versions of the black-and-white glass slides, produced through digitized scans. See here for all the photographs Prokudin-Gorsky took at Yasnaya Polyana. Now that you've seen Tolstoy in color and on film, perhaps you'd like to see him in 3D? In addition to being a very early subject of Russian color photography and film, Tolstoy was also snapped using a sterographic camera. You'll need a pair of Anaglyph glasses (red/cyan) to view the images in 3D. 1) These quotations are my translations from Svetlana Gagarina's Л.Н.Толстой на цветном фото, first published in 1970 in "Наука и жизнь." There are a number of factual errors in the account that I correct above in my discussion of color photography. Michael

A. Denner, |

|