![]()

-

HEALTH CARE AND CONSUMER CHOICE:

MEDICAL AND ALTERNATIVE THERAPIESMerrijoy Kelner and Beverly Wellman

Choosing to Seek Care

Making the choice concerning when and where to seek health care has been shown to be a complex process (Furnham et al, 1995; McGuire,1988). As numerous studies have demonstrated, illness does not always result in a visit to a health care practitioner (Kleinman, 1980; Suchman, 1965; Zola, 1972,1973). Many people delay before making a decision about who to consult for treatment and some never do seek help from the formal health care system. The socio-behavioural model proposed by Andersen and his colleagues is the one that has most frequently been used to analyze the decision to seek health care (Andersen and Newman,1973; Aday and Andersen, 1974, Andersen, 1995). The aim of this model is to delineate conditions that facilitate or impede utilization of health services. It portrays the process of choosing health care as a complex of three interrelated sets of determinants: predisposing factors such as age and education; enabling factors such as knowledge of and accessibility of services, and the need for care.

Most studies that use this model to examine how people seek health care concentrate on the choice to use conventional medical sources. In this paper, we expand the range of this analysis, in a Canadian metropolitan centre, to include the choice of care from alternative practitioners as well as physicians. We do this in the context of what Pescosolido and Kronenfeld (1995) describe as "a renegotiation of the social contract of healing" and the "reemergence of alternative modes of thought and practice about health and illness." (p16). Many people believe that people who use alternative care do so because medicine has failed to help them resolve their health problems. Others, however, argue that at least some alternative patients seek non-medical health care because they are convinced that it is a better form of treatment for them. This research attempts to shed some light on this contentious question.

Choosing Alternative Care

It has been argued, particularly in the medical literature, that people only choose alternative treatments when they have been unable to find help for their health problems from conventional medical services (British Medical Association, 1986; Montbriand and Laing, 1991). On the basis of studies of users of alternative care conducted in both the United States and Britain, Fulder (1988) concludes that people who use alternative practitioners "are mostly refugees from conventional medicine"(p30). Furnham and Smith (1988) also suggest that patients are mainly pushed towards alternative therapies because of negative past experience rather than being pulled by their belief in alternative health care. In other words, this school of thought maintains that people are choosing to use alternative health care principally for pragmatic reasons.

Other scholars who have studied alternative users argue, however, that there is more involved in the choice than mere expediency. A recently published Canadian study of the use of alternative health care by people with HIV/AIDS concludes, for example, that the decision to seek care from alternative practitioners was not born of desperation, but rather, was part of a deliberate strategy and reflected a belief in an "alternative therapy ideology" (Pawluch et al, 1994). The authors propose that this ideology encompasses the following components: 1) definition of the illness as a chronic condition, 2) commitment to a proactive and preventative role in one's health care, 3) a holistic understanding of health as physical, mental, emotional and spiritual well-being, 4) an openness to the full range of available therapies, and 5) an emphasis on individual and personal responsibility for all health care decisions. The study also demonstrates that, at least among this particular population, choosing to pursue alternative treatments did not preclude the choice to use conventional medical services at the same time.

This question is particularly interesting in Canada where the Canadian health care system provides universal coverage for medical care. People who use alternative modalities must pay out of their own pockets. The sole exception is users of chiropractic services who receive small reimbursements from government. Thus, people who venture beyond the medical system are not making neutral decisions. If they remain within the system they are assured that their health care costs will be covered by government insurance and if they go elsewhere they must be prepared to bear the costs of their care.

Support for the notion that use of alternatives is associated with a particular ideological stance is offered by Goldstien in his analysis of the health movement in the United States (1992). He discusses the recent spread of New Age conceptions of healing. While these ideas are diffuse and highly variable, they all emphasize the unity of body, mind and spirit, as well as individual responsibility, antiprofessionalism, self-care and personal transformation or self-realization. He suggests that such a constellation of attitudes encourages people to look beyond conventional medical care and make their own judgements about which types of therapies are the most suitable for their problems.

On the basis of a small-scale study of users of alternative therapies in a non-metropolitan area of Britain, Sharma (1992) argues that both ideological and pragmatic considerations influence decisions about what kind of treatment to seek. The patients of alternative practitioners who she interviewed suffered from chronic illnesses for which conventional medical care had not offered much help. They had turned to alternatives in the hope of finding relief. However, a number of these patients were also ideologically predisposed to try alternative therapies. Many of them took a somewhat critical view of the medical profession. They had concerns about the side-effects of drugs, or were convinced that medicine treats symptoms rather than causes. In addition, they felt it necessary to engage in an active search for information pertaining to their problems, and had considerable confidence in their own capacity to make health care decisions. Sharma found that the people in her sample used alternative therapies in conjunction with conventional medical services; all had consulted their GPs within the past year. Vincent and Furnham (1996) find four principal reasons for people's choice of alternative care: 1) belief in the positive value of alternative care, 2) previous experience of orthodox medicine as ineffective, 3) concern about the adverse side-effects of medical care, and 4) poor communication with patients and orthodox medical practitioners. Other factors mentioned by the patients in this study include the willingness of alternative practitioners to discuss emotional factors and the chance to take an active role in their treatments. This recent study concludes that people decide to seek care from alternative practitioners based on a combination of factors, both practical and ideological.

There is growing evidence that increasing numbers of people in North America and Europe are turning to alternative forms of health care. (Eisenberg et al, 1993; Berger 1993; Yates et al, 1993; Northcott and Bachynsky, 1993; Sharma 1992,1993; Hedley 1992; Saks, 1995). The question of why people are making these kinds of choices thus becomes an important one to investigate.

Users of Alternative Care

In an earlier paper, we have documented the social and health characteristics of people who use alternative health care in a large metropolitan centre in Canada, and contrasted them with patients of family physicians[1] (Kelner and Wellman, submitted ,1996). Marked differences were apparent in the demographic characteristics and health conditions of the two groups. In addition, the research showed that patients of different types of alternative practitioners also differed from each other. The vast majority of people consulting alternative practitioners also saw their family physician at least once a year.

In this paper, we use our data to focus on how and why people choose a particular type of health care. We examine the motivations of patients who seek care from five different types of practitioners; these include four kinds of alternative practitioners: chiropractors, acupuncturists/traditional Chinese doctors, naturopaths and Reiki practitioners; as well as family physicians. We look at the choice of both a particular therapy and a specific practitioner. In our analysis of the factors influencing these choices, we consider not only the nature and duration of the illness, but also predisposing factors such as age, gender, educational level and health beliefs. We also take into account enabling factors such as level of income and knowledge of treatment availability. As well, we explore the possible influence of an "alternative treatment ideology".

METHODS

The Treatment Modalities

We systematically selected five kinds of care: family medicine, chiropractic, acupuncture/traditional Chinese medicine, naturopathy and Reiki healing, to represent a broad spectrum of the many kinds of health care services currently available in Canada.. The therapies selected range from conventional medical care (family physicians) through physical manipulation (chiropractors) and mixed holistic care (acupuncture/traditional Chinese medicine and naturopathy) to care directed primarily at emotional and spiritual healing (Reiki). The spectrum moves from the alternative that is considered the most legitimate and widely accepted (chiropractic), to one of the most unconventional, least well known and least institutionalized (Reiki).

Sample

The sampling strategy, a multistage process, involved identifying, selecting and contacting practitioners and patients of five different treatment modalities. In the first stage, we randomly selected four practitioners from each of the five treatment modalities (5 X 4 =20). The selections were made from professional listings obtained from each of four practitioner associations. In the case of the fifth group Reiki, which does not have a formal association in Canada, we sampled randomly from local listings in alternative directories . In cases where practitioners felt they were too busy, or did not have sufficient numbers of patients, further random sampling was used to contact new practitioners.

In the second stage, each randomly selected practitioner was sent a letter asking them to participate in the study. This was followed by a telephone call, and a brief meeting. We requested that they randomly select 15 patients from their appointment book for a given day, or a series of days, until the required number was reached. Inclusion criteria for the patient sample were: (1) that they be eighteen years of age and over, (2) that they speak English fluently enough to sustain a long interview and (3) and that they be in sufficiently good health to participate. In sum, our data come from 300 patients (15 X 4 X 5 = 300).

In order to minimize rejection and give due respect to the relationship between practitioner and patient, we asked each practitioner to enlist the help of their patients. We provided practitioners with a letter describing the study and assuring them that whatever their decision regarding participation in the study, it would in no way affect their care. If they agreed to participate, the practitioner gave us their names and phone numbers and we contacted them to set a date and time for an interview. Practitioners were not told which of their patients declined to be interviewed. A limitation of the study is that we were not in a position to ensure that all practitioners followed our protocol exactly as we requested.

Data gathering and analysis

Three hundred adults were interviewed in person about their health problems and their use of health care services. The semi-structured interviews were recorded by hand and also by tape, and lasted an average of one hour. The interviews were conducted at the patients' homes, at their workplace, in our offices or in coffee shops, but never on the practitioners' premises.

Responses to the three hundred interviews were coded and entered into SPSS/pc for quantitative analysis. In addition, qualitative analysis was done on the health care histories or narratives of randomly selected patients.

FINDINGS

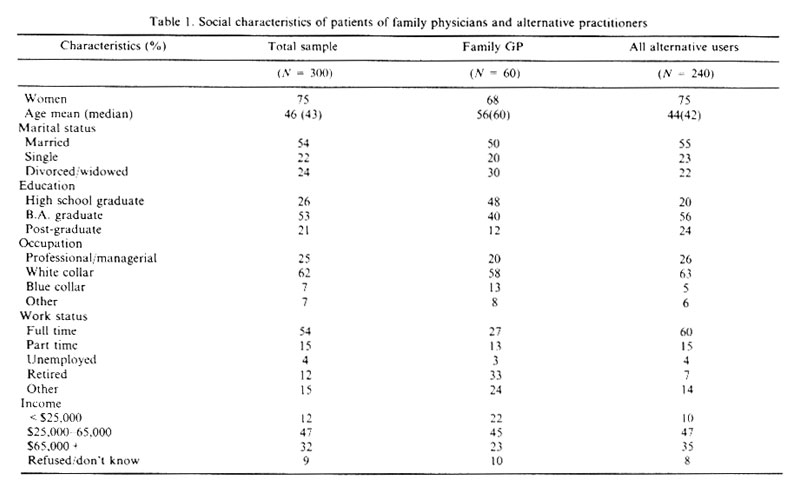

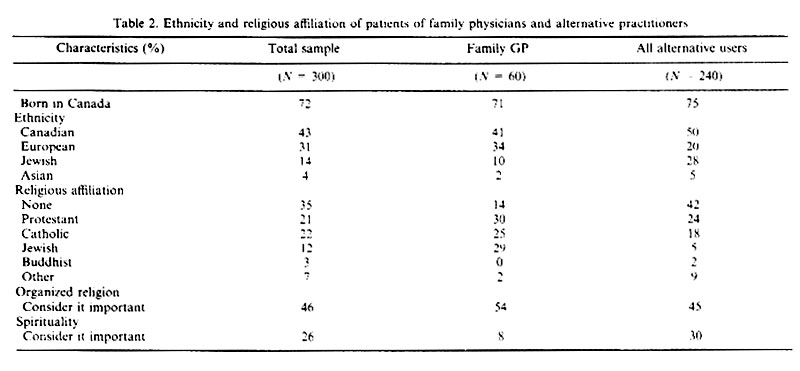

The social and health characteristics of the total sample are depicted in Tables 1 and 2. In addition, these tables show how these characteristics vary between the five treatment groups in the study. In the following section we will outline the key influences that inclined the people in our sample to seek alternative care.

Predisposing factors

Anderson (1968,1973, 1995) argues that certain characteristics will predispose people to use health services. It can also be argued that particular social characteristics such as gender and level of education will predispose people to seek alternative health care. When we compare the demographic profiles of people in the study who use alternative care with people who were consulting family physicians, it is evident that there are marked differences (Tables 1 and 2).

The users of the four kinds of alternative health care investigated in our research (N=240) are all urban residents, are more likely to be female (75% compared to 68% of patients of family physicians), younger (mean age: 44, compared to 56), married (55% compared to 50%), more highly educated (24% have had some postgraduate education compared to 12%), be in higher level occupations (26% are in professional or managerial occupations compared to 20%, and 63% are in white collar jobs compared to 58%), more likely to be employed full time (37% compared to 17%) and to have high incomes (35% earn $65,000 per year or more, compared to 23%). In addition, users of alternative care are more likely to report their ethnic origin as Canadian (50% compared to 41%), to be have no religious affiliation (42% have no religious affiliation compared to 14%), but on the other hand, to say they consider spirituality an important factor in their lives (30% compared to 8%).

This demographic profile of people who use alternative practitioners corresponds to the findings of other empirical research in North America and the United Kingdom (Berger, 1993; Wellman, 1995; Eisenberg, 1993; Thomas, 1991; Fulder, 1988; Sharma, 1992). The key identifying characteristics in these studies are gender, educational level, occupational level, social class and age.

Enabling factors

When Andersen directs attention to enabling factors he is referring to both community and personal resources which make it possible to use health care. In terms of community resources, people who wish to take advantage of alternative services must be located in an area where such services are available, preferably on a regular basis. The urban environment of Metropolitan Toronto provides a diversity of health care services of numerous kinds(Berger, 1993). In 1994 at the start of this research, there were 1,217 family physicians, 477 chiropractors, and 88 naturopaths. The association for acupuncture/traditional Chinese medicine consisted of only seven practitioners who could speak English fluently. In addition, we identified 45 acupuncturists from the yellow pages in the phone book. There were 19 Reiki practitioners listed in various alternative directories. This is clearly a setting with a pluralistic and eclectic range of health resources, including the four types of alternatives examined in this research.

Personal enabling factors for people who make the choice to use alternatives include such things as knowledge of available services, referrals to a particular practitioner, a convenient location, and a level of income that will permit them to pay for treatment and/or private health insurance.

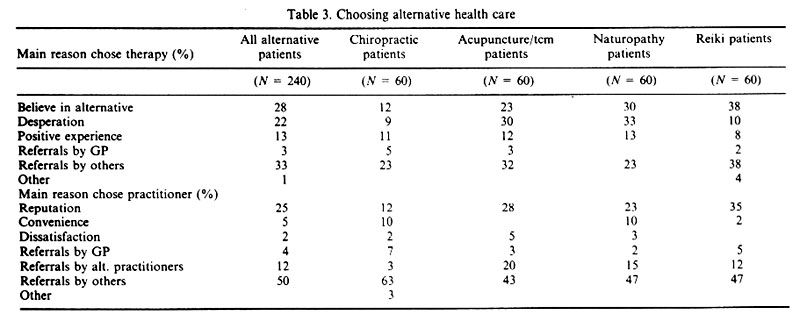

Choosing a therapy

Knowledge about what kinds of health care services are available is essential if people are to make choices about therapies. In addition to the influence of the media, which pays increasing attention to this phenomenon, how do users of alternative therapies find out about them? Over one third (36%) report that they chose to use an alternative therapy because it was suggested by others who had been helped. Referrals came mainly from family members, friends, acquaintances, co-workers and other alternative practitioners. In a handful of cases (3%), an alternative therapy was recommended by the patient's physician. Another thirteen percent said that they had a positive previous experience with alternative treatments (the same one they were currently using or another type) and that this was the principle influence on their choice this time. (Table 3)

There is definite variation in the extent of referrals among the different alternatives. More than one quarter (28%) of the chiropractic patients said that referrals were the main reason they chose that particular therapy, while some, (11%) were influenced by a positive experience in the past with some form of alternative care. For acupuncture\tcm patients, referrals influenced over one third (35%) and past experience was a positive factor for twelve percent of them. In the case of naturopathic patients, referrals were less influential; just under one quarter (23%) said they had chosen naturopathy on the basis of a referral and another thirteen percent chose this kind of therapy because of a successful past experience with an alternative practitioner. For clients of Reiki healers, referrals were an important factor (40%) and previous experience with alternative care was a key element in the choice of eight percent. Clearly, personal resources, (i.e., who you know) are crucial for obtaining information about alternative therapies. These personal resources also provide stepping stones to actually using alternatives.

Choosing a practitioner

In selecting a practitioner, personal referrals from satisfied patients were even more important; 62% of the users of alternatives found out about their practitioner through a family member, a friend, an acquaintance, a co-worker, another alternative practitioner, or in a very few instances (4%), were referred by a physician. Another one quarter (25%) chose their practitioner because of his/her reputation; they had either read about them in alternative publications, observed them in other settings and been impressed, or heard from others that this practitioner was able to deal with difficult, complex problems (Table 3).

Again there were differences among the four alternative modalities. Referrals were the main reason for choice of practitioner for almost three quarters (73%) of chiropractic patients and for twelve percent, it was the reputation of the chiropractor. For patients of acupuncture\tcm doctors, referrals accounted for the majority's (66%) decision to use a particular practitioner and reputation accounted for over one quarter (28%). For sixty-four percent of naturopathic patients, referrals were the main reason for selecting their practitioner and reputation accounted for nearly one quarter (23%). In the case of clients of Reiki practitioners, referrals also accounted for sixty-four percent of their choices and reputation was the key factor in the choice of thirty-five percent. These patterns make it evident that social relations play an important role in providing prospective patients with the information and contacts they need to seek out alternative practitioners. Moreover, referrals serve to validate the use of a particular practitioner.

Location

A location that is not too difficult to reach or too far away is also an enabling factor for many people. In the choice of a particular type of therapy, no one in the sample of alternative users mentioned convenience as an influence. In the choice of a practitioner, however, five percent said that a convenient location was the main reason they chose the practitioner they were currently consulting. Only two of the groups, patients of naturopaths and patients of chiropractors, reported that convenience was the main factor in their choice (10% of both).

Ability to pay

Finally, the ability to pay for treatment is clearly a consequential factor in the utilization of health care services. We have already seen that the incomes of the alternative users in the study are higher than the sample who were using conventional medical care. They are thus in a better position to pay privately if they choose to use alternative treatments. Only in the case of chiropractic patients, (one quarter of the alternative users) are treatments partially covered by government reimbursement. For the other alternative therapies, payment must come either out of their own pockets or from their private insurance.

Previous studies (Eisenberg et al, 1993; Fulder, 1988) have shown that income level is an important factor for people seeking alternative care. This is particularly important since alternatives are rarely supported by government insurance plans and only partially supported by private insurance. Referrals by family, friends and acquaintances have also been shown to be particularly powerful factors which encourage people to seek out alternative practitioners (Sharma, 1992). She points out that it is personal recommendations that initially create interest and later, it is assurances from others that alternative treatments have been efficacious that encourage use. Knowledge about alternatives that is gained through the lay referral network is more powerful as a legitimating influence than knowledge acquired through impersonal sources such as advertising and the media.

The need for care

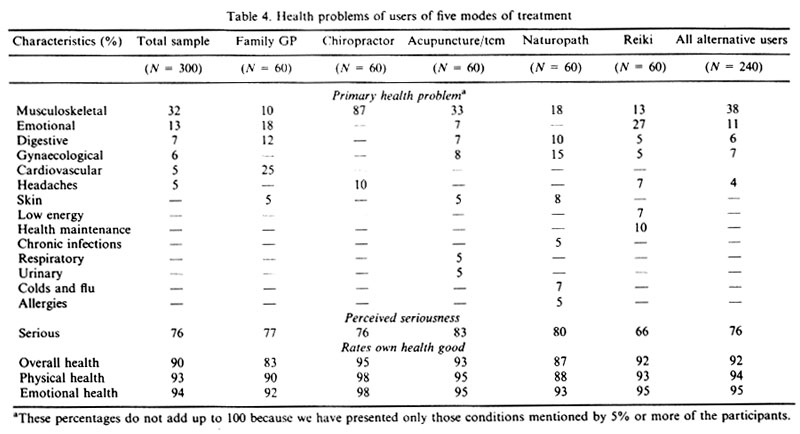

The 240 people in our sample who were consulting alternative practitioners did so for a variety of ailments, mainly chronic. (Table 4) The most frequently mentioned presenting problems were musculoskeletal (38%), emotional (11%), gynaecological (7%), digestive complaints (5%) and headaches (5%). As could be expected, there was variation among the different treatment groups, with chiropractic patients more likely to seek care for musculoskeletal problems and clients[2] of Reiki practitioners more concerned about their emotional health and with maintaining and improving their well-being.

Over three quarters of the patients using alternatives considered their health problems to be serious. Again, there was some variation between groups; patients of acupuncturists were the most likely to perceive their problems as serious (83%), while clients of Reiki practitioners were the least likely (66%). In spite of this, the great majority of people who were consulting alternative practitioners (92%) regarded themselves as healthy and rated their physical and emotional health as good. Indeed, alternative patients rated their overall health higher than the patients of family physicians.

Length of time with problem

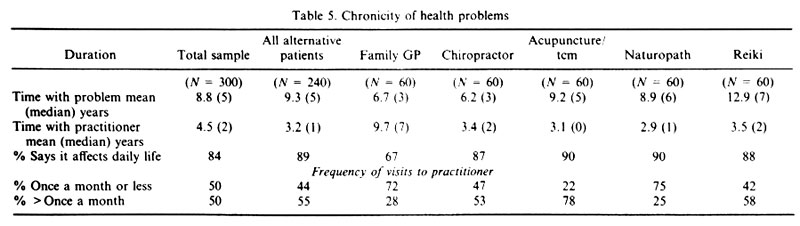

The mean number of years that the 240 patients of alternatives in the study had suffered with their primary health problem was higher (9.3, median=5) than it was for the patients of family physicians (6.7, median=3). Among the four types of alternative therapies, the mean number of years with their problem was lowest for chiropractic patients (6.2, median=3) and highest for Reiki clients (12.9, median=7; Table 5)

Length of treatment

Patients of family physicians had been seeing their practitioners much longer ( mean of 9.7 years, median 7) than the patients who were consulting alternative practitioners ( mean of 3.2, median=1). There was little variation among the four kinds of alternative patients in this respect. However, when we look at the frequency with which people were visiting their practitioners, it is evident that patients of alternative practitioners see them more often than do the patients of family physicians. Taken as a whole, over half (55%) of the alternative patients visit their practitioners for help with their primary health problems more than once a month, while close to one half (44%) report that they see them once a month or less. In comparison, only twenty-eight percent of patients of family physicians visit them more than once a month and nearly three quarters of them (72%) see them once a month or less. (Table 5)

Effect on daily life

All the people in the study were asked whether their primary health problem affected their daily life in some fashion. There was a clear difference between the patients of alternatives and patients of family physicians. The vast majority (89%) of alternative patients reported that their problem definitely affects their daily life. They talked about pain and discomfort, they spoke of moodiness and depression, they mentioned physical limitations, weakness, social isolation, difficulties at work and financial losses. All four groups of alternatives reported the same pattern. Considerably fewer (67%) of the patients of family physicians (67%) felt that their illness was affecting their daily lives. It seems that the negative impact of illness on their lives and their inability to function effectively have been important factors in influencing people to choose an alternative mode of health care.

Chronicity of Health Problems

There is support from other studies for the findings in this research that people typically use alternative care to help alleviate chronic conditions rather than acute or life-threatening illnesses (Eisenberg et al, 1993; Sharma, 1992; Wellman, 1995; Furnham et al, 1995; Berger, 1993). The main ones tend to be musculoskeletal, allergies, arthritis and stress related conditions such as headaches, anxiety and digestive problems.

Unlike most other studies, this research goes beyond identifying specific health problems by considering such factors as how long people have had the condition, how serious they feel it is, and how it affects their daily life. The need for care increases when people perceive that their condition is interfering with their ability to function, socially or physically, in their daily life (Zola, 1973). The people in our sample report that they have been suffering with their health problems for a long period of time. Perhaps this explains why they consider their problems to be serious in spite of the fact that they say their physical and emotional health are good. While the patients of family physicians have been seeing their practitioners longer than the patients who were consulting alternative practitioners, alternative users visit their practitioners more frequently, particularly at the early stages of the therapy. This pattern is associated with the kinds of treatment that alternative practitioners use. Rather than administering drugs and medical tests and then waiting for changes to occur, most alternative treatments are based on consistent attention and monitoring over time.

AN ALTERNATIVE IDEOLOGY?

It has been argued that people who use alternative health care services do so because they subscribe to a distinctive set of beliefs about health, illness and healing, sometimes called an alternative treatment ideology (Pawluch et al 1994; McGuire, 1988, Goldstein, 1992; Coward, 1989). While Andersen considers health beliefs to be one aspect of predisposing factors, here we examine them separately because of their importance in the literature and in the reports of the patients in our study.

Push and pull influences

The interview responses of the 240 patients of alternative practitioners reveal a mixed picture. Some have chosen alternative care for purely pragmatic reasons such as "nothing else has really helped" (AP103).[3] On the other hand, a number report that their choice is based on a belief system that includes such tenets as "holistic care, diet and natural forms of healing".(NP448)

When the alternative patients explained why they chose a particular therapy, nearly one quarter (22%) said it was out of desperation; they had tried conventional medical care and had not been helped. As a chiropractic patient declared "Everything else had failed. I had already tried relaxants and antiinflammatories, bed rest and physiotherapy. It was either go to the emergency department or find some kind of alternative" (CP206). Over a quarter of them (28%) however, reported that they had chosen an alternative therapy because they believed in it and in its principles. For example, a patient of an acupuncture/traditional Chinese medicine practitioner reported that he had chosen that type of therapy "Because of my philosophical knowledge about meditation, breathing, martial arts and how the energy works in the body. I knew about energy points in the body and the unity of body, mind and spirit." (AP105) This patient is expressing a commonly held belief among users of alternatives that good health care must be based on a holistic view of the connection between physical, mental and spiritual well-being.

Some differences in motivation are evident among the various alternative groups. Only nine percent of the chiropractic patients mentioned desperation as the reason for their choice and twelve percent mentioned belief in this type of care. Among acupuncture\tcm patients, almost one third (30%) mentioned desperation while nearly one quarter (23%) mentioned belief. For naturopathic patients, desperation was mentioned by one third (33%) and belief by thirty percent. For Reiki clients desperation was reported by only ten percent and belief by thirty-eight percent. It seems that a belief in the particular type of treatment is more powerful among naturopathic patients and Reiki clients as compared to chiropractic and acupuncture/tcm patients who more often mention that they have given up hope that conventional medicine can help their problem.

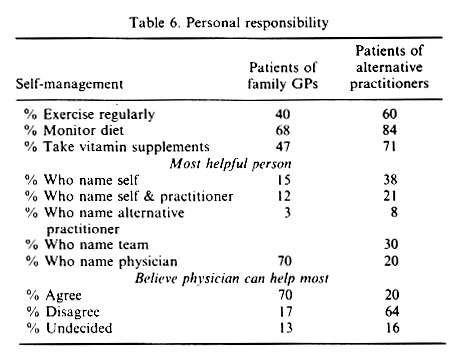

Personal responsibility

An important element of the alternative ideology is said to be "an emphasis on personal and individual responsibility over all health care decisions" (Pawluch et al, p65). Most all of the people who were using alternatives reported that they take a proactive role in maintaining their own health and preventing illness. Sixty percent of the alternative patients said they followed a regular exercise regimen (compared to 40% of the physician patients), 84% said they monitored their diets (compared to 68% of the physician patients) and 71% reported that they regularly take vitamin supplements (compared to 47% of the physician patients). When asked who they thought could help them most with their health problems, the alternative patients made it clear that they relied mainly on themselves for help. Over a third of them (38%) said they believed that they alone would be the most helpful and another fifth (21%) declared that they in partnership with their practitioner could help most with their health problems. In contrast, the patients of family physicians were more likely to subscribe to the belief that for most illnesses, it is the physician who can help them most. Close to three quarters of them (70%) said they agreed with this, whereas only one fifth (20%) of the alternative patients supported this statement (Table 6).

Patients of alternative practitioners clearly see an important role for themselves in their own health care. They emphasize the patient's responsibility toward his/her own health, as well as making it clear that they know their own body best and trust their own judgement most. A chiropractic patient declared that "You have to use your own commonsense; it can prevent a lot of problems." (CP239). A Reiki client put it this way: "By educating yourself regarding health and well-being, your body, what's going on in your body, and different health related issues, you can make the most appropriate decisions about your own health care." (RC504). A patient of an acupuncture/tcm doctor explained "Every patient is individual. You have to rely on your own intuition because no one remedy works for two people. You need to consider health holistically and consider all aspects of your life." (AP136).

This sense of personal responsibility is felt more strongly by patients of Reiki practitioners than by any of the alternative users; over half (58%) said that they were the most helpful person in solving their health problems and over a quarter (20%) said that they, together with their practitioner could best resolve their problems. The Reiki clients also had the highest rate of disagreement (83%) with the statement that it is the physician who can help the most with health problems.

Thus, our findings partially support the argument that an alternative ideology exists and exerts an influence on some individuals who choose alternative care. With the exception of one aspect of Goldstein's formulation of the ideology - anti-professionalism, the other elements delineated by Pawluch (1994), Goldstein (1992) and Sharma (1992) are evident in the interviews conducted for this research.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The data presented here demonstrate that the behavioral model developed by Andersen and colleagues can be fruitfully applied to the use of alternative, as well as conventional medical services. All three factors (predisposing, enabling and need for care) were found to influence people in their choice of practitioner - medical as well as alternative. While the model applies to all choices of health care, the influence of specific aspects of the three factors is different for different groups. For example, if we examine the impact of the need for care we see that alternative users suffer predominantly from chronic ailments which have not responded successfully to medical treatment but continue to negatively affect their daily lives. In the case of predisposing factors, a high level of education has been shown to be a key determinant of alternative use. As for enabling factors, a high level of income is a critical consideration since users of alternative care pay primarily out of their own pockets for these services.

Even within the four modes of alternative treatment examined here, the extent of influence of the three factors varies in interesting ways. For example, people who seek care from acupuncture/tcm and Reiki practitioners are more highly educated than users of other alternatives and more likely to consider spirituality an important factor in their lives. Those who use naturopaths rate their overall physical health lower than others who use alternatives. The Andersen model has been of considerable value in explaining why people choose to seek health care. What this paper contributes is the assurance that this model can be to applied to health care that extends beyond medical services.

A number of scholars have suggested that there exists an alternative ideology or philosophy which inclines people to consider a wider range of possibilities for maintaining and improving their health. What this study confirms is that an alternative ideology (i.e., health beliefs) does influence some individuals to consult unconventional practitioners. The study also demonstrates that not all users of alternative care subscribe to this ideology; some have completely pragmatic reasons, such as disenchantment with orthodox medicine, for seeking alternative care. Among those who do believe in alternative therapies, only certain elements of the ideology are salient to them; not everyone is convinced of the total "message". It seems likely that if people continue with their treatment and find it successful, they will become more open to the ideology even if it seems obscure. Future papers will explore this postulate.

Individuals in this study who have chosen to try alternative treatments have essentially taken their health and well being into their own hands. In choosing alternatives to improve their health or overcome their health problems they are going beyond conventional practice and taking the risk of using treatments that have yet to be validated by scientific evidence. In taking such action they are exerting active control over their own health problems.

McGuire (1985) speaks of the 'flexible self', one that is able to draw upon a variety of resources in the search for better health and personal growth. This flexible self is free to choose from a range of options for the care of the self and the body. For these people, conventional medicine becomes just one of the options from which they can select a form of treatment. In the 1990's we are seeing increasing numbers of 'smart consumers'; people who are well informed about health issues and up-to-date on the latest 'infomessage' from the media. These are consumers who prefer to use their own judgement and the guidance of personal referrals to make health care decisions. Rather than relying on institutional legitimacy for making their choice (i.e., the medical profession, hospitals and clinics), they rely on personal legitimacy as the basis for selecting alternative care.(Haug and Lavin, 1983). Their decisions are individual ones, in which they act as concerned consumers rather than compliant patients.

These consumers do not make dichotomous choices between medicine and alternative care. Rather, they are choosing specific kinds of practitioners for particular problems. It is misleading to assume that people will only choose one kind of health care. For example, they choose chiropractors for backaches, naturopaths for colds, and Reiki practitioners for emotional stress. Sometimes they choose a mixture of treatments for a specific problem. They may see both a family physician and an acupuncturist for allergies or skin disease. Many use multiple therapies concurrently. An individual may see a physician for heart problems, a chiropractor for headaches, and a naturopath for fatigue.

"Smart consumerism" is encouraged by several factors. Perhaps the most influential is the extensive and consuming interest in health and the body that characterizes Western society today. People are bombarded daily with reminders that they are fragile, that their days are numbered, and that they can take steps on a personal level to postpone deterioration and mortality. In addition, a wide range of possibilities for health care is provided by the many different kinds of alternatives currently available. Furthermore, consumers are influenced by the public and private testimonials about successful alternative treatments which have recently become common. The result is that more and more people are deciding that they are willing to take a chance on alternative approaches to coping with their health problems.

REFERENCES

Aday, Lu Ann and Ronald M. Andersen. 1974. "A Framework for the Study of Access to Medical Care." Health Services Research 9:208-20.

Andersen, Ronald M. 1968. Behavioral Model of Families' Use of Health Services. Research Series No. 25. Chicago, IL: Center for Health Administration Studies, University of Chicago.

Andersen, Ronald M. and John F. Newman. 1973. "Societal and Individual Determinants of Medical Care Utilization in the United States." Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly Journal 51:95-124.

Andersen, Ronald M. 1995. "Revisiting the Behavioral Model and Access to Medical Care: Does It Matter?" Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36(1): 1-10.

Berger, Earl. 1993. The Canada Health Monitor, Survey No. 9, March, p. 123, Price Waterhouse, Toronto.

British Medical Association. 1986. "Alternative Therapy." Report to the Board of Science and Education. London: BMA.

Coward, R. 1989. The Whole Truth: The Myth of Alternative Health, London: Faber and Faber.

Eisenberg, David, Ronald Kessler, Cindy Foster, Francis Norlock, David Calkins and Thomas Delbanco. 1993. "Unconventional Medicine in the United States: Prevalence, Costs and Patterns of Use." The New England Journal of Medicine 328:246-252.

Fulder, Stephen. 1988. The Handbook of Complementary Medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Furnham, Adrian and Smith, Chris. 1988. "Choosing Alternative Medicine: A Comparison of the Beliefs of Patients Visiting a General Practitioner and a Homeopath." Social Science and Medicine 26(7):685-689.

Furnham, Adrian, Charles Vincent and Rachel Wood. 1995. "The Health Beliefs and Behaviors of Three Groups of Complementary Medicine and a General Practice Group of Patients. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 1(4):347-59.

Goldstein, Michael. 1992. The Health Movement: Promoting Fitness in America. New York: Twayne.

Haug, Marie and Bebe Lavin. 1983. Consumerism in Medicine: Challenging Physician Authority. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Hedley, Alan. 1992. "Industrialization and the Practice of Medicine: Movement and Countermovement." International Journal of Comparative Sociology 33(3-4):208-14.

Kelner, Merrijoy and Beverly Wellman. 1996. "Who Seeks Alternative Health Care: A Profile of the Users of Five Modes of Treatment. Submitted for publication.

Kleinman, Arthur. 1980. Patients and Healers in the Context of Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press.

McGuire, Meredith. 1988. Ritual Healing in Suburban America. New Brunswick: Rutgers University.

Montbriand, M. and G. Laing. 1991. "Alternative Health as a Control Strategy." Journal of Advanced Nursing 16:325-32.

Northcott, Herbert and John Bachynsky. 1993. "Concurrent Utilization of Chiropractic, Prescription Medicines, Nonprescription Medicines and Alternative Health Care." Social Science and Medicine, 37(3):431-35.

Pawluch, Dorothy, Roy Cain and James Gillett. 1994. "Ideology and Alternative Therapy Use Among People Living with HIV/AIDS." Health and Canadian Society 2(1):63-84.

Pescosolido, Bernice and Jennie Kronenfeld. 1995. "Health, Illness, and Healing in an Uncertain Era: Challenges from and for Medical Sociology." Journal of Health and Social Behavior: Extra Issue 5-33.

Saks, Mike. 1995. Professions and the Public Interest. London: Routledge.

Sharma, Ursula. 1992. Complementary Medicine Today: Practitioners and Patients. London: Routledge.

Suchman, Edward. 1965. "Stages of Illness and Medical Care." Journal of Health and Human Behaviour 6:114-28.

Thomas, Kate J., Jane Carr, Linda Westlake and Brian T. Williams. 1991. "Use of Non-Orthodox and Conventional Health Care in Great Britain." British Medical Journal 302(26):207-210.

Vincent, Charles and Adrian Furnham. 1996. "Why do patients turn to complementary medicine? An empirical study." British Journal of Clinical Psychology 35:37-48.

Wellman, Beverly. 1995. "Lay Referral Networks: Using conventional medicine and alternative therapies for low back pain." Pp. 213-238 in Research in the Sociology of Health Care (1995), Volume 12 Ed. Jennie J. Kronenfeld. Greenwich: JAI Press.

Yates, Patsy, Geoffrey Beadle, A. Clavarino, Jake Najmen, Damien Thomson, Gail Williams, Lisbeth Kenny, Sydney Roberts, Bernard Mason & David Schlect. 1993. "Patients with Terminal Cancer Who Use Alternative Therapies: Their Beliefs and Practices." Sociology of Health and Illness 15(2):199-216.

Zola, Irving. 1972. "The Concept of Trouble and Sources of Medical Assistance--To Whom One Can Turn, With What and Why." Social Science and Medicine 6:673-79.

Zola, Irving. 1973. "Pathways to the Doctor: From Person to Patient. Social Science and Medicine 7:677-89.

ENDNOTE

[1]In Canada, the terms family physician and general practitioner are used synonymously

[2] Reiki practitioners consistently refer to the people they treat as clients rather than patients.

[3] Quotations are identified by letters to represent the type of modality : CP for chiropractic patient, AP for acupuncture\tcm patient, NP for naturopathic patient and RC for Reiki client, as well as the number of the interview schedule from which they are taken.

|

|