![]()

-

Older Adults’ Use of Medical and Alternative Care

Beverly Wellman, Merrijoy Kelner and Blossom T. Wigdor

University of TorontoIntroduction

Interest in and use of complementary and alternative medicine has been increasing dramatically in recent years. A significant proportion of the population in Western society are now using unconventional forms of health care (Astin, 1998; Eisenberg et al., 1993, 1998; Ernst, 1995; McGregor & and Peay, 1996). In Canada, where alternative medical care is not covered by the otherwise inclusive health care system, reports estimate that at least 3.3 million people sought treatment outside of the medical establishment in 1995 and have spent at least one million dollars that were not reimbursed from provincial health plans (Statistics Canada, 1995). While these are current estimates, much less is known about older adults. This article provides a descriptive analysis of older adults who are patients almost exclusively of conventional health care and compares them with patients found at the offices of practitioners of alternative health care (chiropractors, acupuncturists/traditional Chinese medicine doctors naturopaths and Reiki healers).[1]

Research questions

In this study we ask: 1) Do older adults seek care for their health problems from alternative practitioners, and if so, do the alternative care patients differ in their social and health characteristics from those who do not? 2) What are the pathways older adults follow when they seek care from alternative practitioners and do these differ from the pathways pursued by older adults who consult their family physicians?

Conventional medical care

Research has shown that a small segment of older people accounts for a disproportionately large amount of the use of medical services, particularly at the end of life (Kane & Kane, 1978; Roos, Shapiro & Roos, 1984; Wolinsky, Mosely & Coe, 1986). While older adults consult their physicians for acute as well as chronic problems, many older persons underutilise physician services for chronic conditions and preventive health care (Haug, Belgrave & Gratton, 1984; Levkoff, Cleary, Wetle & Besdine, 1988). This may be because chronic conditions are difficult to treat and many physicians do not offer preventive care to the elderly. Older people often decide just to “live with the problem” rather than continue to pursue medical care. Nevertheless, Haug, Wykle and Namazi (1989) found that the faith of older adults in physicians tends to be high, even though nearly half the people in their sample claimed to have been in a situation where a physician made a mistake in their care.

Alternative health care

Since older adults tend to have more chronic illnesses than younger people (Kart, 1997; Marshall, McMullin, Ballantyne, Daciuk & Wigdor, 1995; Verbrugge 1986), and the most common problems brought to alternative practitioners are chronic in nature, ( Kelner & Wellman, 1997; Vincent & Furnham, 1996), we began this research with the assumption that a high proportion of people who seek out alternative therapies would be older adults. This is in spite of the understanding that patients from earlier generations were devoted adherents to conventional medicine. Previous research indicates that in general users of alternative care are younger, predominantly female, well educated, relatively affluent and less likely to be affiliated with formal religions (Kelner & Wellman, 1997).[2]

Pathway Studies

Pathway studies make it possible to specify linkages between different practitioners as patients negotiate their way to health care (e.g., Strain, 1990). Instead of addressing the question of who uses health care services, the emphasis here is on why and how an individual seeks health care (Sharma, 1992; Zola, 1973). In order to shed light on how people decide what kind of care they will seek, we examine the influence of family, friends, lay others and health care providers (McKinlay, 1973; Pescosolido, 1986; Pilisuk & Park, 1986; Salloway & Dillon, 1973). Who people know and speak with about their health have been shown t be important sources of information and connections to others who may be of use (Valente, 1995).

Methods

The study population

In order to focus on the use of conventional and alternative health care by older adults, we selected a subsample from a larger study of 300 patients from 20 to 90 years of age conducted in 1994-95 (Kelner & Wellman, 1997). The 77 older adults analyzed here were members of the larger sample who were 55 years of age and over [14 in their late 50's, 36 in their 60's, 20 in their 70's and 7 between the ages of 80 and 90].

The original research project from which these older adults were identified was designed to investigate the health care practices of patients in Toronto, Canada who were consulting either family physicians or one of four kinds of alternative practitioners (chiropractors, acupuncture/traditional Chinese medicine doctors, naturopaths, and Reiki healers). These five modes of treatment were chosen because they represent a spectrum of the many types of services currently available in the Toronto area. The choice of alternative services was designed to reflect the range from the most widely accepted and legitimate (chiropractic) to one of the least well known and least institutionalized (Reiki).

Sample

To identify the larger sample of patients, we used a multistage strategy. In the first stage, we randomly selected four practitioners from each of the five treatment modalities (5x4=20) to assist us in enlisting patients to study. The selections were made from professional listings obtained from each of four practitioner associations. In the case of the fifth group, Reiki, which does not have a formal association, we sampled randomly from local listings in alternative directories. In cases where practitioners felt they were too busy or had insufficient numbers of patients, further random sampling was used to contact additional practitioners.[3]

Once the practitioner agreed to take part, we requested that they enlist the first 15 patients from their appointment book for a given day, or a series of days, until the required number was reached (Because we had no direct involvement in the recruitment of patients, we cannot be certain about the rate of refusal). Inclusion criteria for the sample were that they: (1) be willing to be interviewed, (2) be eighteen years of age and over, (3) speak English fluently enough to sustain a long interview, and (4) be in sufficiently good health to participate.

When a patient agreed to be interviewed by us, the practitioner gave us the name and phone number and we contacted them to set up an appointment in another venue. In this paper, we report only on the data from the 77 patients in the study who were 55 years and over.

Data Gathering

Semi-structured interviews were recorded by hand and by tape, and lasted an average of one hour. Interviews were conducted at the patients' homes, their places of work, at our offices, or in coffee shops -- but never on the practitioners' premises.

We asked patients to provide us with a personal health history dealing with the primary health problem that brought them to seek care from the practitioner in whose office we had located them. To minimize selective recall of events and information, we focused in detail on the most recent health problem that had brought them to treatment. We also probed the process of decision-making that led to choice of therapy and practitioner. In addition, we collected information on social-demographic characteristics, as well as their health narratives concerning who referred them for care, who they spoke with about their health, and the various types of health care practitioners they had been consulting for their problem.

To test the extent of skepticism about medical doctors among the patients in our sample, we created a scale using five of the eight questions from the World Health Organization’s questions on medical scepticism (Kohn & White, 1976). We eliminated those questions closely correlated to each other and modified the remaining questions to clarify the meaning. For example, people were asked on a five point Likert scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree, whether drugs that physicians prescribe are better than other remedies.

Data Analysis

Much of the data were derived from closed-ended questions and were analysed using quantitative methods. The responses to the interview schedule were entered into SPSS/pc. Because we were dealing mainly with categorical measures of the social and health characteristics of the patients, we used chi-square to identify (at the 0.05 level) significant differences between the patients of family physicians and the patients of alternative practitioners. Because of the small numbers who used each type of alternative therapy, we compared the patients of family physicians with the patients of all four alternative practitioners (grouped together).

The open-ended questions in the interview schedule were analysed using qualitative methods including content analysis and constant comparison (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1990). The exact words used by the patients provided the original codes for organizing the responses. The codes were then refined and condensed to provide the key themes conveyed by the patients. The health narratives provided the data for the construction of the pathways.

Results

Distribution of Patients

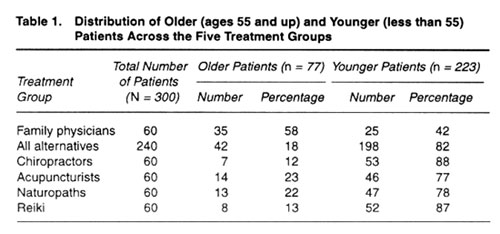

The 77 older adults were distributed in a strikingly unequal manner (Table 1). Very few, only 42 of the 240 alternative patients in the total sample were older adults. In comparison, more than half (35 ) of the 60 patients of family physicians were 55 years or more. While the number of older adults seeing family practitioners and those seeing alternative practitioners seem on the surface to be relatively similar, it is important to realize that the relative percentages of the two groups are widely divergent (18% versus 58%). The fact that only a small percentage of older adults currently use alternatives has also been identified in a recent newsletter of the National Advisory Council on Aging (1997). The pattern changes, however, when we consider the younger people in the sample. Many more people under the age of 55 (82%) were consulting alternative practitioners.

Social Characteristics of the Sample

The 42 older adults who were consulting alternative practitioners were distinctive in a number of ways (Table 2). They were more likely to be female, have graduated from university, to be in managerial or professional occupations and to have higher household incomes. They were somewhat more likely to have been born outside of Canada and to describe their ethnic origins as non-Canadian. They were also less likely to have a formal religious affiliation, although a number of them mentioned the importance of spirituality per se as a guiding force in their lives.

It is noteworthy that close to half (46%) of the older adults are retired so that the impact of their illness on work is not an issue for them. Furthermore, the difference in the ages of the family physician group (mean = 69) and the alternative group (mean = 65) means that many of the family physician patients have been retired for several years while the alternative patents have just approached retirement age.

Primary Health Problems

The patients of alternative practitioners were also quite different in the nature of their primary health problems. Alternative patients cited problems such as musculoskeletal (50%), and emotional (10%) conditions as their primary reasons for seeking care. Although there is some evidence that people use alternative therapies when they have life-threatening illnesses such as cancer and AIDS( Pawluch, Cain & Gilbert, 1994), few such illnesses showed up in this sample. The family physician patients were seeking care mainly for cardiovascular conditions such as heart problems, high blood pressure and high cholesterol (43%) and digestive complaints (20%). By contrast, none of the alternative patients reported cardiovascular conditions as their primary reason for seeking care.

Perceptions about Health

When it came to how they felt about the meaning of good health, the older adults who were seeing alternative practitioners were no different than the others. Two facets of good health were important for them all. The most frequently mentioned (43%) was the ability to function at a high level on a daily basis. This ability was also described as "freedom to do what I want", " having energy and vitality", and "thinking positively". The absence of symptoms such as pain and discomfort was second in importance (29%). The primary concern was ability to carry on daily activities.

The alternative patients were less likely to worry about their health than were the patients of family physicians (24% of the alternative patients said they had no worries versus 17% of the others). Fewer of the alternative patients expressed the concern that their current health problems would continue and possibly exacerbate over time (14% of the alternative patients versus 25% of the rest).

Functional Disability and the Need for Care

The decision to adopt some kind of health care has been linked to interference of an illness with daily life ( Mechanic, 1982; Zola, 1973). There is a significant difference between the alternative care patients and the family physician patients in their perceptions of the degree to which their health problems were placing limitations on their lives. While 90 per cent of the patients of alternative practitioners reported that their disability was impinging on their ability to function normally, only 60 per cent of the patients of family physicians said their health problem was interfering with their lives on a daily basis. In both cases, fatigue and physical limitations were the primary complaints.

One aspect of interference is an inability to carry out work obligations. About one quarter (26%) of both groups found that their problems made work harder, and another 10 per cent of the alternative group said that they were actually compelled to miss work.

Functional disability also affects people's lives in terms of the way they interact with their family and friends. Slightly more of the alternative care patients (39% as compared to 31% of the family physician patients) said that their disability made them less responsive to their family and less able to carry out their family responsibilities. Alternative patients also reported more limitations on their social activities (49% compared to 37% of the family physician patients).

Consulting Medical and Alternative Practitioners for Health Problems

The older adults in this study had all made the decision to seek some kind of professional care, since it was through their practitioners that we identified them. When their problems had first interfered with their daily living, most indicated that they had tried some self-care measures and had consulted with their informal health networks. Sooner or later, they decided to seek care from a professional. The health narratives of those who were consulting alternative practitioners reveal that a majority (67%) had first consulted a physician, and that many were subsequently sent to a number of medical specialists. When medical care no longer seemed sufficient to help them with their condition, alternative therapies provided an option. Most of these alternative patients said that by the time they consulted an alternative practitioner, their situation had deteriorated. In contrast, most family physician patients said they went to their doctor soon after they became aware of their symptoms. There was usually only a delay of a few days.

There was also a sizeable group (33%) of older adults who went directly to alternative practitioners for their primary health problem. This was especially true for chiropractic patients. Some of these did so because they had previously had a successful experience with alternative care. Others subscribed to what has been called the "alternative ideology" (Pawluch, Cain & Gilbert, 1994); that is, they had a different philosophy about the nature of health and healing from that advocated by conventional medicine and were uneasy about the use of drugs and surgery. Others had relatives, friends and colleagues who strongly recommended not only a therapy but a practitioner.

The length and frequency of practitioner visits differed for the two groups. Patients of alternative practitioners had been consulting their practitioners for a relatively short time (mean = 3 years), compared to family physician patients who had been seeing their doctors for a much longer time (mean = 10 years). Family physician patients see their doctors less frequently than the patients in the alternative group: 28 per cent of the family physician patients go more than once a month, whereas over half (53%) of the patients of alternative practitioners go more than once a month. This pattern is associated with the fact that alternative treatments typically require numerous visits, at least during the initial stages.

Our data show that the older adults consulted other kinds of health practitioners for their health problems. In the case of family physician patients, it was mainly other types of medical practitioners and services to date. Only a very few had ventured to consult alternative practitioners (mainly chiropractors) at any time. It is possible, however, that some of these older adults will eventually decide to seek care from an alternative practitioner if their health problems are not satisfactorily resolved. However, there may be a group of older adults who will always be too sceptical or too fearful of alternative care to ever consider this option. By comparison, the alternative care patients had used a wider range of types of alternative practitioners. The most frequently consulted were: chiropractors, 93%; acupuncture/traditional Chinese medicine doctors, 62%; naturopaths, 57%; homeopaths, 55%; physiotherapists, 52%; and herbalists, 50%.

The pattern of multiple use of health care providers also extended to visits with family physicians. The great majority of alternative care patients (86%) reported that they had a family physician and saw him/her at least once a year. Half of these physician visits were for annual checkups and monitoring of chronic conditions and medications. Other health problems that prompted the alternative care patients to consult family physicians were musculoskeletal conditions (10%), cardiovascular problems (8%) and colds or "flu" (8%). Nonetheless, when examining the health care pathways of the various patient groups, several patterns of use became obvious.

Typical alternative pathways demonstrate a combination of medical and alternative use. Moreover, those who use alternatives, in addition to chiropractics, use several kinds of therapies and often many therapists until they find the one that satisfies their needs. For example, upon examining the pathway of a naturopathic patient who is a 60 year old woman with a longstanding illness common to older people (arthritis), it is notable that family physicians refer to specialists and relatives and friends refer to alternatives (Figure 1). The typical pathway illustrated by the case of this woman, transpired over ten years and included a family physician, a specialist doctor, self care, lay consultation and the use of a naturopath and a second naturopath. The patient began with prescribed medications and cortisone shots. While this tended to be effective at first, it became less so over time. When these proved to be ineffective (about three years prior to the interview), her son’s friend recommended his naturopath. She changed her diet, her pain disappeared and she began with a second naturopath only because the first one moved out of the country.

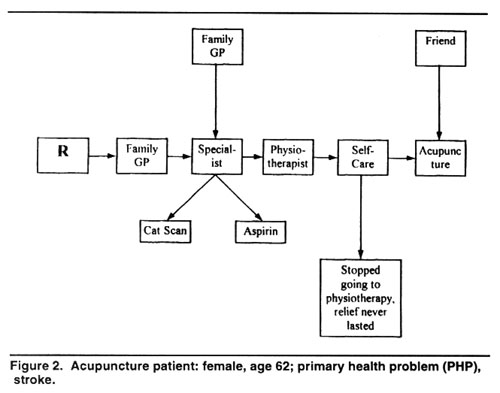

A second example is also female (Figure 2). She is 62, a patient who consulted an acupuncturist for care due to a stroke. Her pathway included her family physician, a specialist doctor, a physiotherapist, self care and lastly, an acupuncturist. Similar to figure 1, the family physician referred her to a medical specialist, while a friend advised acupuncture. In both cases, use of an alternative therapist did not preclude the use of medical care for the same problem.

When we examined a third pathway of a Reiki patient with cancer who is female and 60 years of age, we noted the use of many medical doctors and two kinds of alternative therapists (Figure 3). It is noteworthy that alternative therapists are the last ports of call for help and not the first. This woman went from a specialist to another specialist to a surgeon and used self-care before turning to a homeopath and lastly a Reiki practitioner.

By comparison, a typical physician patient pathway, although it includes self-care and discussions with friends, is characterized mainly by different types of medical care. The case of a family physician patient demonstrates the concise pathway for a typical heart condition problem (Figure 4). This man (77 years old) went to his family physician on the advice of his wife, and then a second family physician after the first one retired. He was then referred to a cardiologist who referred him to a cardiac surgeon. The question is why do some patients stay within the medical sphere, while some others seek help from alternative practitioners?

Explaining Older Patients' Choices

The reasons for deciding to consult a family physician or an alternative practitioner are reflected in the language that patients use when they recount their health histories. Alternative care patients express their ongoing search for help in statements like:

“I prefer natural remedies that have no side effects rather than the physician prescribed medications that didn’t help and only made things worse”;

“I had to find a way to deal with my problem. This was a last resort --I saw every specialist and still no answer";

“I feel the acupuncturist gets to the root of the evil.”

Family physician patients tend to explain their decisions to seek care more in terms of trust and belief in their doctor's authority and expert skills. For example:

“Everyone should have a family physician because he knows your background. I put my trust in his decisions. I think he’s very knowledgeable and he’s caring” “I’ve always gone to see a family physician whenever something I thought needed treatment. It’s a normal reaction to see a doctor. I rely on my doctor to know if the problem is little or big; this is something only a physician can confirm”

There are two kinds of decisions required when people make choices about using health care services. First, they must decide which kind of therapy and then which practitioner to consult. The responses of our older adult patients suggest that the two decisions often become blurred into one and the choice of therapy and practitioner are made simultaneously. For example, people may hear of a practitioner who has been successful in relieving problems like theirs, and decide to consult him/her whatever the type of therapy practised. Nevertheless, for purposes of clarity, we present these choices separately here.

Choice of therapy: When asked why they chose their current therapy, the responses of the two groups of older adults showed significant differences. The vast majority (83%) of the family physician patients expressed a strong belief in medical care. On the other hand, the reasons cited by the alternative patients were varied: some (31%) made their choice on the basis of their belief in the superior benefits of alternative care; another 12 percent reported that they were influenced by a prior positive experience with alternative care; others mentioned referrals from friends, family or other members of their social network (36%) and still others said they were motivated by a sense of desperation because they had not been able to find relief through self-care or medical care (19%). Only one patient made the choice of an alternative therapy on the basis of a referral from a physician.

Choice of practitioner: When it came to selecting a particular practitioner, referrals by family, friends, coworkers and others were the most important influence on both groups of patients (family physician patients, 40%; alternative patients, 55%). Referrals by another physician also had an important effect on the choice of family physician by their patients (14%), as did a strong belief in medicine (20%). In the case of the alternative patients, one quarter (26%) of them made their choice on the basis of the practitioner’s reputation. The information about these practitioners came from sources such as newspapers, television or public lectures, since there are no central registries of approved practitioners. Referrals from other alternative practitioners also influenced the choice of some alternative patients (10%).

Someone to talk with: The older patients in this study did not lack people to talk with about their health, nor did they lack people who could supply them with relevant health information (health informants). Indeed, alternative patients had more people to talk to than did patients of family physicians and these health informants were mainly family and friends. In the case of patients of family physicians, family members comprised slightly more than half (55%) of the people who provided some type of health support, while friends comprised only about one-fifth (21%). Similarly, family also played an important role for alternative patients, but friends generally provided an even larger amount of support and information; just over a third (36%). It is important to recognize that some alternative patients had medical doctors as well as alternative practitioners (11%) as their health informants, whereas patients of family physicians had only medical doctors.

Scepticism about Medicine: It is not surprising that the two groups of patients differed in their views regarding the ability of medicine to help them with their health problems. The results of the modified World Health Organization’s scepticism scale (Kohn & White, 1976) showed that patients of alternative practitioners were more doubtful about the practice of medicine (mean = 3.8) than the family physician patients (mean = 2.6). Alternative patients proved to be much more sceptical than physician patients with regard to the following statements:

• "For most kinds of illness, it is the physician who can help you most” (24% alternative patients versus 83% physician patients agree);

• "Drugs physicians prescribe are better than other remedies" (80% alternative patients versus 20% of physician patients disagree);

• "If you follow a physician’s advice you will have less illness in your lifetime” (22% alternative patients versus 68% physician patients agree);

• “Physicians can prevent most serious illnesses” (14% alternative patients versus 40% physician patients agree);

• "I doubt some of the things physicians think they can accomplish” (65% alternative patients versus 49% physician patients agree).

Although the responses to the last two items show considerable scepticism on the part of physician patients toward physicians' claims, the alternative patients' scepticism is markedly stronger. These findings support those of Furnham and Forey (1994) in Great Britain who similarly found that patients of alternative practitioners were more critical of the efficacy of medicine.

When asked who they thought could help them most with their health problems, the alternative care patients replied that they relied mainly on themselves. Over one third of them

said they believed that they alone would be the most helpful and another fifth thought that they, in partnership with their practitioner could help the most. The patients of family physicians, however, were much more likely to subscribe to the belief that for most illnesses, the physician would be the most helpful (83% vs. 24% of the alternative care patients).

Discussion

Limitations of the study make it unwise to claim generalizability for the findings. The sample of older adults is small and there is potential bias in the choice of patients by practitioners since we were not in a position to ensure that all practitioners enlisted their patients exactly as we instructed them. We therefore make no claims that the patterns revealed by the data are representative of the total population of older adults. We believe, however, that the study yields important insights and identifies some trends in the health care behavior of older adults.

The findings suggest that there are only a few older people currently turning to alternative therapies and practitioners for their health care. This is in spite of the fact that older adults suffer predominantly from chronic conditions which are the very kinds of problems that are most often presented to alternative practitioners. Their reluctance to try other options is undoubtedly related to the fact that this cohort of older adults grew up believing heavily in the power of scientific medicine and in the authority of experts like physicians. However, the popularity of alternative care among younger people today may mean that in the future, more people over 55 years of age will be using the services of alternative practitioners. This study shows that those older people who are prepared to venture into new territory and make use of non-insured alternative health care services are distinctive in a number of ways.

There is a difference in the kinds of health problems that older adults bring to alternative practitioners. They consult them primarily for chronic problems such as arthritis or back pain which they perceive as discomforting and intruding in their daily lives. The patients of family physicians, on the other hand, turn to their doctors for conditions which they feel are more worrisome and possibly life-threatening (such as heart problems). These patterns suggest that people regard more serious or life-threatening types of problems as the domain of physicians who are perceive as authoritative experts, rather than consulting alternative practitioners whose expertise is not so widely established. The fact that alternative patients are less worried about their health may also be related to the distinctive kinds of health problems for which they seek non-medical care.

The two groups of patients also display different social characteristics, with alternative care patients being better educated and more affluent. The most obvious implication of these differences is that alternative care patients have more disposable income to use for uninsured health care. The older adults who chose to use alternative therapies could more easily afford to pay the out of pocket expenses required. These differences in social characteristics provide older adults who use alternatives with more social capital; that is they are better educated, have larger and broader social networks which provide them with diverse kinds of health care information. All of these factors combine to facilitate the use of alternatives by people with higher social class status.

The pathways to care followed by the two groups of patients were also different. At the beginning, the older adults in both groups mainly consulted with their family physicians. In most cases, the family physicians referred them to medical specialists. Most patients followed the suggestions of their doctors but some felt that either they were not being helped or they were not receiving the kind of support and care they needed. These patients were encouraged to try alternative care by family and friends and sometimes by other alternative practitioners who had become friends in the process of caring for other health problems. Here we see a pattern in which patients of family physicians get health information primarily from family and physicians. Alternative patients, however, have more sources to turn to for information; friends are more important in the consultation process and so are other alternative practitioners.

The length of pathways was somewhat longer for alternative patients who had tried more kinds of therapies and practitioners. Although the pathways have been presented here in a linear fashion, it must be remembered that patients were often using different therapies simultaneously while at the same time giving consideration to using others and also employing self-care measures. The findings of this study make it clear that pathways to care are untidy and cannot be captured in an orderly, organized picture.

Explaining why some of the older adults in this study chose to consult alternative practitioners proved to be a complex process. The findings show that there is no simple explanation for the appeal of alternative therapies. For most, they offered hope for relief from persistent chronic conditions, but the basis for this hope varied. Some believed that alternative forms of care were more holistic and effective, others had been helped with health problems before, still others heard that friends or family members had been successfully treated, and some chose alternative therapy out of a sense of desperation about alleviating their discomfort. Moreover, the choice to use alternative services did not mean that these older patients had decided to leave their physicians. They typically maintained close ties with

them, in spite of consulting alternative practitioners as well. It is clear that the choice of an alternative therapy cannot be accounted for without understanding the meaning such a therapy has for the individual user.

Conclusion

As the number of people who consult alternative practitioners continues to rise, we can expect that a greater proportion of older adults will use alternative health care in the future, probably integrating it with conventional medical care. The potential spread of alternative services has several implications for policies that affect older adults. It will be important that reliable information be available about the efficacy and safety of these services, both for the older adults who may wish to use them and for the physicians who may recommend them for chronic conditions. At the present time, research funds to establish the validity of alternative therapies are only minimally available. Government funding to carry our high quality research in this area should be a priority for the future.

There is also an important role for government to play in ensuring that alternative practitioners are adequately educated, accredited and regulated. Regulatory bodies need to be established to ensure that professional standards are developed and adhered to. For a diverse field like alternative care, this is an enormous undertaking and one that will require time, patience and a degree of cohesiveness and co-operation that is not yet evident among alternative practitioners.

If satisfactory standards of quality control are established, governments that support national health insurance may consider including alternative services in insurance schemes for older adults. In the United States, HMOs have begun to incorporate alternative services into their health plans and most of the major national health insurance plans are investigating the inclusion of alternative therapies (Weeks & Layton, 1998).

A recent report indicates that 78% of the older adults in Canada have at least one chronic problem (Tamblyn & Perreault, 1998). The report also expresses concern that there is evidence of overuse of prescription drugs among the elderly. One possible remedy for this problem may lie in the increased use of alternative services to relieve chronic conditions. If these alternatives are helpful, older adults will be able to take an active part in the society without experiencing the adverse consequences of over medication.

Increased use of alternatives by older adults in the future has the potential to enhance their comfort and well-being, but policy initiatives need to be developed that will ensure the effectiveness, safety and accessibility of these unconventional health services.

List of authors' and co-authors' names, addresses, etc

Beverly Wellman (Tel) 416 - 978 - 1787 (Fax) 416 - 978 -4771

(Email) bevwell@chass.utoronto.caMerrijoy Kelner (Tel) 416 - 978 - 1787 (Fax) 416 - 978 -4771

(Email) merrijoy.kelner@utoronto.caBlossom Wigdor (Tel) 416 - 978 - 4706 (Fax) 416 - 978 -4771

(Email) b.wigdor@utoronto.ca

Institute for Human Development, Life Course and Aging

University of Toronto

222 College Street, Suite 106

Toronto, Ontario M5T 3J1

References

Astin, J. A. (1998). Why patients use alternative medicine: Results of a national study. Journal of the American Medical Association 279:1548-53.

Berliner, H. S., & Salmon, J.W. (1980). The holistic alternative to scientific medicine: History and analysis. International Journal of Health Services 10:133-147.

Eisenberg, D. M., R. C. Kessler, C. Foster, F. E. Norlock, D. R. Calkins, & Delbanco, T. L. (1993). Unconventional medicine in the United States: Prevalence, costs and patterns of Use. New England Journal of Medicine 328:246-252.

Eisenberg, D. M., R. B. Davis, S.L. Ettner, S. Appel, S. Wilkey, M. Van Rompay, & Kessler, R. C. (1998). Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997: Results of a follow-up national survey. Journal of the American Medical Association 280:1569-75.

Ernst, E. (1995). Complementary medicine: Common misconceptions. Journal Review of Social Medicine 88:244-247.

Furnham, A., & Forey, J. (1994). A comparison of health beliefs and behaviours of clients of orthodox and complementary medicine. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 50:458-469.

Gevitz, N. (Ed.). (1988). Other healers: unorthodox medicine in America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Chicago: Aldine.

Haug, M., L. L. Belgrave, & Gratton, B. (1984). Mental health and the elderly: Factors in stability and change. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 25:100-115.

Haug, M. R., M. L. Wykle, & Namazi, K. H. (1989). Self-care among older adults. Social Science and Medicine 29:171-183.

Kane, R. L., & Kane, R. A. (1978). Care of the aged: Old problems in need of new solutions. Science 200:913-919.

Kart, C.S. (1997). The realities of aging: an introduction to gerontology. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Kelner, M., & Wellman, B. (1997). Health care and consumer choice: Medical and alternative therapies. Social Science and Medicine 45:203-212.

Kohn, R., &. White, K. L. (1976). Health care: an international study. London: Oxford University Press.

Levin, J. S., & Coreil, J. (1986). New age healing in the U.S. Social Science and Medicine 23:889-897.

Levkoff, S. E., P. D. Cleary, T. Wetle, & Besdine, R. W. (1988). Illness behavior in the aged: Implications for clinicians. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 36:622-629.

Marshall, V. W., J. A. McMullin, P. J. Ballantyne, J. F. Daciuk, & Wigdor, B.T. (1995). Contributions to independence over the adult life course. Toronto: Centre for Studies of Aging, University of Toronto.

McGregor, K. J., & Peay, E.R. (1996). The choice of alternative therapy for health care: Testing some propositions. Social Science and Medicine 43:1317-132.

McKinlay, J. (1973). Social networks, lay consultation and help-seeking behavior. Social Forces 51:275-292.

Mechanic, D. (Ed.). (1982). Symptoms, illness behavior, and help-seeking. New York: Prodist.

National Advisory Council of Aging. (1997). Alternative medicine and seniors: an emphasis on collaboration. Ottawa: Government of Canada.

Pawluch, D., R. Cain, & Gilbert, J. (1994). Ideology and alternative therapy use among people living with HIV/AIDS. Health and Canadian Society 2:63-84.

Pescosolido, B. (1986). Migration, medical care preferences and the lay referral system: A network theory of role assimilation. American Sociological Review 51(August):523-540.

Pilisuk, M. & Parks, S.H. (1986). The healing web. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England.

Roos, N.P., E. Shapiro, & Roos, L.L. (1984). Aging and the demand for health services: Which aged and whose demand? The Gerontologist 24:31-36.

Salloway, J. & Dillon, P. (1973). A comparison of family networks and friend networks in health care utilization. Journal of Comparative Family Studies 4(1):131-42.

Sharma, U. (1992). Complementary medicine today: Practitioners and patients. London: Tavistock/Routledge.

Statistics Canada. (1995). National population health survey overview 1994-1995. Ottawa: Minister of Supply & Services.

Strain, L. A. (1990). Lay consultation among the elderly. Journal of Aging and Health 2:103-122.

Strauss, A., and Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newberry Park, California: Sage.

Tamblyn, R. & Perreault, R. (1998). Encouraging the wise use of prescription medication by older adults. Pp. 340 in Adults and seniors: Determinants of Health, edited by National Forum on Health. Quebec: Editions MultiMondes.

Valente, T.W. (1995). Network models of the diffusion of innovations. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Verbrugge, L.M. (1986). From sneezes to adieux: Stages of health for American men and women. Social Science and Medicine 22:1195-1212.

Vincent, C. & Furnham, A. (1996). Why do patients turn to complementary medicine?: An empirical study. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 35:37-40.

Weeks, J. & Layton, R. (1998). Integration as community organizing: Towards a model for optimizing relationships between networks of conventional and alternative providers. Integrative Medicine 1:15-25.

Weil, A. (1995). Spontaneous healing. New York: Fawcett Columbine.

Wolinsky, F.D., R. R. Mosely, & R.M. Coe. (1986). A cohort analysis of the use of health services by elderly Americans. Journal of Health and social Behavior 27:209-219.

Zola, I. K. (1973). Pathways to the doctor: From person to patient. Social Science and Medicine 7:677-689.

ENDNOTE

[1]. Chiropractic is a system of manipulation of the spine and the joints based on the view that maladjustments of the vertebrae interfere with the healthy operation of the nervous system. Acupuncture works on the theory that meridians, or energy channels, link inner organs to external points of the body. Treatment involves applications of needles at external points along these meridians. Naturopathy is based on the theory that therapy should mobilize the body’s inherent capacity to heal itself. Treatment focuses on the whole person and may include a wide range of therapies. Reiki healing emphasizes the mind, body, spirit connection. Therapy consists of hands on, non-invasive techniques which use “universal life-force energy” to deal with emotional and other problems.

[2]. As yet, there is no consensus on how best to describe this diverse set of non-medical health care therapies; sometimes called alternative, complementary, holistic, unorthodox or marginal. The common thread is that they do not focus solely on biomedical processes, nor do they fit under the rubric of scientific medicine (Berliner & Salmon, 1980; Levin & Coreil, 1986). While the form and content of each alternative may be quite different, most share underlying concepts of the body's natural ability to heal itself (Gevitz, 1988; Weil, 1995). Alternative therapies tend to emphasize the harmonious integration of body, mind and spirit, and regard disease as having dimensions beyond the "purely biological". In this study we adopt the term 'alternative' health care, to describe the multitude of therapies provided by non-medical practitioners.

[3]. It was only necessary to approach more practitioners for three of the five groups. For family physicians and Reiki, we were obliged to contact eight practitioners in order to enlist four. It was not too dissimilar for naturopaths; we contacted seven to arrive at four.

|

|