![]()

-

THE THERAPEUTIC RELATIONSHIPS OF OLDER ADULTS: COMPARING MEDICAL AND ALTERNATIVE PATIENTS

Merrijoy Kelner and Beverly Wellman, University of Toronto

Over the course of their lives, most people have had the experience of dealing with health problems. What is different about being elderly is that the incidence of health problems tends to increase with advancing age, and most ailments become chronic (Brody 1985). Unlike acute illnesses, these chronic conditions (e.g. arthritis, hypertension, heart disease and emotional problems) cannot be cured, they can only be alleviated. They require a process of sustained supportive care, often over long periods of time, which means that the experience of illness is prolonged and often frustrating.

Although conventional medicine has had dramatic successes in treating acute illnesses, it has not been as effective in dealing with chronic conditions. When older adults are unable to find relief, they sometimes explore other avenues to relieve the discomfort, anxiety and inconvenience caused by their health problems (Chappell 1987; Kelner, Wellman and Wigdor 1996). Most studies of older adults with health problems focus on their encounters with physicians. This paper looks at the experiences of 77 older adults in the Metropolitan Toronto area who were receiving care from either family physicians or selected alternative health care practitioners for the symptoms they were experiencing during 1994-95. We examine their health care narratives and also their responses to specific questions concerning their relationship with their practitioners. Health narratives have been used by other sociologists to study how people perceive their health problems and also how they view their medical encounters (Mishler 1984; Waitzkin et al. 1994; Brody 1987, 1991). In this paper we concentrate on one particular facet of the health care experience; the therapeutic relationship between older patients and their practitioners. Important elements of this relationship are the preferred roles and expectations that people bring to the encounter.

Roles and Expectations

Research on the relationship between physicians and their patients over the last two decades emphasizes that people have differing expectations regarding their roles in the healing process (Haug and Lavin 1983; Lupton 1997). Some want their physicians to control the course of communication and make the important decisions regarding their health care. This type of therapeutic relationship has been referred to as the paternalistic model (Parsons 1951). Others expect to have a more egalitarian relationship with their health provider in which there is sharing of information and also of decision-making (Szasz and Hollender 1956; Katz 1984). It has been claimed that the elderly adhere to the more passive model ( Blaxter and Patterson 1982); Greene et al. 1994) and to have lower expectations with respect to the quality of their health care (Cohen 1996). This more deferential style of interaction has been attributed to lower levels of education among those born before World War II, a greater respect for authority and a greater dependency on health care as people age (Haug 1994).

Among the population in general, the nature of the relationship between patients and practitioners has been increasingly influenced by the an emphasis on personal responsibility for health and health care (Coward 1990) and a decline in the status and autonomy of the professions (Hafferty and McKinlay 1993). People are said to be seeking a greater role in the healing process and to be more interested in assuming control over their health care (Haug and Lavin 1983; Mechanic and Schlesinger 1996). We are seeing growing numbers of 'smart consumers' who are well informed and prefer to use their own judgement and the advice of friends and family to cope with their health problems (Kelner and Wellman 1997). A recent opinion poll conducted in Canada (CTV/Angus Reid 1997) reports that an overwhelming majority (93%) of people feel they are in control of their own health and that it is their personal responsibility to maintain good health. This change reflects a new paradigm in health care in which the emphasis shifts from automatic compliance with experts, to shared decision-making and a partnership role between patients and practitioners (Krupat et al. 1999).

While most patients today want to take an active role in their own care, research shows that it is the patients of alternative practitioners who are most likely to take an active and responsible stance (McGuire 1988; McGregor and Peay 1996; Kelner and Wellman 1997). Patients who consult alternative practitioners have been found to exhibit a greater determination to make their own choices about the best way to deal with their health problems and to seek a more egalitarian relationship with their health care providers (Sharma 1992). This approach to health care seems particularly suited to older people and their health complaints, since it encourages ongoing discussions with practitioners regarding progress or the lack of it and flexibility in treatment according to results.

In addition to roles and expectations, another key element of the therapeutic relationship is the trust that patients place in their health care provider.

Trust, Attention and Time

Fundamental to the paternalistic model of the doctor-patient-relationship developed by Parsons (1951), is the element of trust in the physician's expertise and beneficence. The assumption is that patients will comply with their doctors' advice because they trust them to make the best possible decisions about their care, putting the patient's interests first. Indeed, trust has been called the basic building block of doctor-patient interaction (Rogers 1994).

With the general societal shift, however, toward shared decision-making and more informed and questioning patients, it can be expected that the element of trust will be less important in the therapeutic relationship. Alternative patients, in particular, have been shown to behave as astute, informed consumers within a pluralistic health care system, selecting the type of therapy and practitioner they believe will help them most (Cassidy 1998; Kelner and Wellman 1997). McGuire (1988, p197) describes people who use alternative practitioners as "contractors" of their own care, making selective choices of therapies based on their values and beliefs about health and illness. The issue of trust in this kind of relationship needs to be explored. We expect to find less trust in the physician's expertise in diagnosis and treatment and more confidence in the patient's own judgement among the older adults who were consulting alternative practitioners.

Research on patient satisfaction with medical care indicates that patients want to have more personal and collegial relationships with their practitioners (Lewis 1994; Greene et al. 1994). Patients complain of lack of time with their doctors as well as depersonalized attention. They would like to feel that they are not being rushed and that their psycho-social needs are being attended to. Alternative practitioners typically adopt a more holistic approach to care, taking into consideration the role of the mind in healing and the influence of a wide range of factors on health and illness (Weil 1995). Conventional medical practice, on the other hand, often limits itself to focusing on the body, as distinct from the mind and spirit. Health problems have usually been conceived in the narrow sense, as "disease", although the recent emphasis on patient-centered care implies a wider focus. (Hafferty and Light 1995).

We expect that the family physician patients in the study will report that they would like relationships with their doctors that entailed more time and attention to their particular life situation. The alternative patients on the other hand, can be expected to cite lack of personalized attention and time with their family physicians as reasons for their shift to alternative practitioners.

RESEARCH STRATEGY

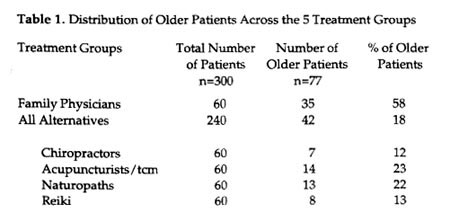

In order to gain an in-depth understanding of the ways that older adults perceive their relationships with their practitioners, we selected a sub sample of 77 patients who were 55 years and over, from a much larger sample of 300 persons from 20 to 90 years of age. The original research project from which the older adults were identified was designed to investigate the health care practices of patients in Metropolitan Toronto who were consulting one of five kinds of health care practitioners, selected to represent a spectrum of the health services available in the Toronto area. The range of services extended from the most common type of medical care (family physicians), to a popular form of physical manipulation (chiropractic), to mixed forms of holistic care (acupuncture/traditional Chinese medicine and naturopathy), to care directed primarily at emotional and spiritual healing (Reiki). The choice of the four alternative modes of treatment was designed to reflect a spread from the most widely accepted and legitimate alternative (chiropractic) through one of the least well known and least institutionalized (Reiki).

This diversity of health care modes made it possible to examine whether there were differences in the therapeutic relationships of older patients who were seeing family physicians and those who were consulting alternative practitioners. For purposes of clarity, we have combined the patients of the four kinds of alternative practitioners into one group, called "alternative patients'. This analytic strategy, however, represents a pragmatic compromise, since it does not adequately reflect the diversity of therapies covered by the term "alternative health care", the different kinds of settings in which care is given, nor the various kinds of therapeutic relationships that are possible for patients of alternative practitioners.

METHODS

In order to identify a sample of patients , we used a multistage strategy. The first step was to select a group of practitioners who were willing to enlist some of their patients in the study. For the larger study we needed a total sample of 300 patients who were using one of the five kinds of treatment modes identified above.

Recruitment of Practitioners

In the first stage, we randomly selected four practitioners from each of the five treatment modalities (5 x 4 = 20). Selections were made from professional listings obtained from the practitioner associations. In the case of the Reiki practitioners who do not have a formal association in Canada, we sampled randomly from listings in local alternative directories. In cases where practitioners felt they were too busy or had insufficient numbers of patients, further random sampling was used to contact additional practitioners.

Recruitment of Patients

We asked the practitioners to recruit their own patients. This strategy was adopted in order to protect the privacy of the relationship between practitioner and patient. Once practitioners had agreed to participate in the research we requested that they randomly enlist 15 patients from their appointment book for a given day, or series of days, until the required number was reached. A limitation of the study is that we were not able to ensure that all practitioners followed the research protocol and enlisted patients exactly as we had instructed them.

When a patient agreed to take part, the practitioner who had enlisted them gave us their name and phone number and we contacted them to set a date and time for the interview. Inclusion criteria for the patient sample were that they: (1) be eighteen years of age and over, (2) speak English fluently enough to permit a long interview, and (3) be in sufficiently good health to participate.

Data Gathering

The semi-structured interviews were recorded by hand and also by tape and lasted an average of one hour. To assure confidentiality interviews were never conducted on the practitioners' premises, rather, we saw the older adults at their homes, in our offices, at their workplace or in coffee shops. We asked patients to tell us about the primary health problem that had brought them to the practitioner who enlisted them in the study. To minimize selective recall of events, we focused on the most recent condition that had prompted them to come for treatment and asked participants to tell the story of their illness. In addition to collecting data on their sociodemographic characteristics, we asked the patients to how and when they had chosen that particular therapy and practitioner and what they did about self-care and health maintenance, we then questioned them in detail about the nature of the relationship they had with the practitioner who had enlisted them in the study.

Although the data were collected at only one point in the health care narrative of the respondents, we tried to compensate for this problem by encouraging people to reconstruct the process by which they had come to seek health care. We then asked them to describe what happened as they moved from the initial appearance of symptoms through to their current situation. With only 77 older (55 years of age or more) respondents, we should be cautious about making generalizations. We believe, however, that we have been able to capture some patterns that are typical of other groups of older patients.

Data Analysis

The open- ended questions were analyzed using the qualitative research method of content analysis in order to make comparisons between groups (Morgan 1993, Denzin and Lincoln 1994). The exact words used by the participants provided the original codes for organizing the responses. Transcripts were segmented into small but meaningful sections of text. Each section was assigned one or more descriptive conceptual labels. The segmented, labeled transcripts were then compared within and between interviews. Initial labels were refined to establish consistent codes which could generate conceptual categories for describing the quality of the therapeutic relationship. The prevalence of each category was recorded and descriptive statements about them were developed using the patients' own words. The categories that emerged from the analysis reflect the headings such as "trust” and "expectations" that are used here to organize the findings. For the health narratives, we used NUD.IST (a software program for analyzing qualitative data) to identify themes and patterns.

The closed-ended questions were coded and entered into SPSS/pc. Descriptive statistics (frequency distributions, range, means and standard deviations as appropriate) were generated for all the relevant variables. Because we were dealing mainly with categorical measures of the social and health characteristics of these older patients, chi-square was used to identify (at the 0.05 level) significant differences between the patients of family physicians and the patients who were consulting alternative practitioners.

Description of the Sample

The older adults in the study were distributed in a strikingly unequal manner (Table 1). In spite of our expectation that older adults would be major users of alternative care because their health problems were primarily chronic, it turned out that very few of them were using alternative practitioners. Only 42 of the 240 alternative patients in the total study were 55 years of age or over. Analysis revealed that the older adults in the study were heavy users of conventional medical care; more than half (35) of the 60 patients in the total sample who were seeing family physicians were 55 or more. While the numbers of older patients consulting family practitioners and those seeing alternative practitioners seem on the surface to be relatively similar, the relative percentages of the two groups are widely divergent (58% of the family physician patients were older adults versus 18% of the alternative patients). Other research confirms our finding that only a small percentage of older adults are currently using alternative care (National Advisory Council on Aging 1997; Thomas et al. 1991).

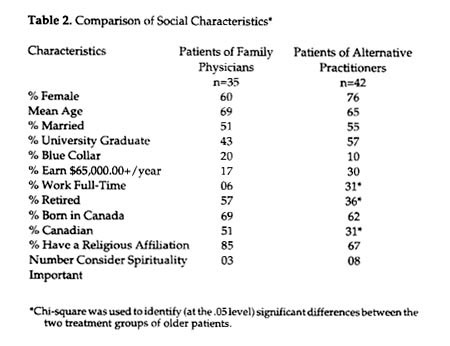

The social characteristics of the older adults who had ventured to use alternative practitioners differed in interesting ways from those who had stuck with conventional medical care (Table 2). The alternative patients were more likely to be female, to have graduated from university, to be in managerial or professional occupations and to have higher household incomes. One obvious consequence of these differences in socioeconomic status is that the patients of family physicians had fewer financial resources with which to purchase uninsured (ie. non-medical) health care services and are thus less likely to use any kind of alternative care.

The alternative patients were also more likely to have been born outside of Canada and to describe their ethnic origins as non-Canadian, perhaps supporting a cultural tradition of using alternative care. They were less likely to have a formal religious affiliation, but a number of them mentioned the importance of spirituality per se as a guiding force in their lives. This spiritual aspect of healing is more pronounced in some forms of alternative healing (e.g., Reiki healing) than in others (e.g.. chiropractic) but it is clearly an element of the whole perspective on alternatives (Gevitz 1988).

Health Profile of the Sample

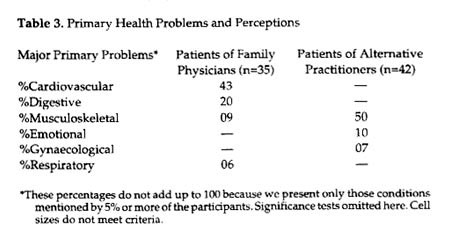

Despite many common ailments experienced by both groups of older adults, the presenting health problems differed by type of health care provider (Table 3). Close to one half (43%) of the family physician patients sought care for life-threatening problems such as cardiovascular conditions like high blood pressure and high cholesterol and one fifth (20%) were seeing their physicians for digestive complaints. In contrast, half (50%) of the alternative patients were seeking care for less alarming problems such as backache and arthritis, while another 10% were seeking relief from emotional problems. It seems that the older adults regarded certain conditions, usually the more life-threatening ones, as the domain of medicine, whereas they believed that ongoing, troublesome debilitating problems that were nevertheless not life-threatening, were more amenable to alternative care. Some potentially serious conditions such as cancer and HIV also prompt patients to try alternative therapies but in these cases, they are used mainly for palliation rather than relief from symptoms (Pawluck 1994)

Most (90%) alternative patients reported that they also saw a family physician at least once a year. They told us that they had gone mainly for physical checkups, monitoring of medications, colds and flu. The family physician patients also consulated others, mainly specialist doctors (94%) but also some allied practitioners such as physiotherapists (46%), and massage therapists (20%).When they sought alternative care, they went primarily to chiropractors (43%). Few or none had sought care from the less recognized alternatives such as Reiki healers, herbalists or reflexologists.

Now that we have identified the social characteristics and primary health problems of the two groups of older patients, we examine the way they view their relationships with their practitioners.

THE NATURE OF THE THERAPEUTIC RELATIONSHIP

Roles and Expectations

How did these older adults see their own role in the healing process and what were their expectations?

The older adults who were consulting alternative practitioners expected to take an active role in maintaining their health and conducting their health care. They told us that they prefer to take personal responsibility for maintaining their health and preventing illness, reporting that they follow a regular exercise regimen, monitor their diets and regularly take vitamin supplements. Some of the patients of family physicians also said they like to assume a proactive role in promoting and managing their health, but this pattern was more common among the users of alternative care. Indeed, when asked whether they believed that for most kinds of illness it is the physician who can help most, 83% of the family physician patients agreed whereas only 24% of the alternative patients concurred with this statement. Well over half (59%) of the alternative patients expressed the view that they alone or in partnership with their practitioner who could help them most with their health problems. These differences in orientation were reflected in the language they used. In general, the patients of family physicians tended to use passive phrases like: "I was referred to" or “I was told" or “I was prescribed". In contrast, the patients of alternative practitioners tended to use more active language such as "I decided" or "I wanted" or "I needed".

The greater accent on personal responsibility among alternative patients can be linked, at least in part, to the nature of their primary health problems. The patients of alternative practitioners were consulting them mainly for less serious although troublesome problems, both physical and emotional, whereas the family physician patients were prompted to seek care by more life-threatening kinds of problems. It is easier to rely on one's own judgement in the case of conditions where the risks are not as great and there is time to try out different treatment strategies.

Among these older adults, the alternative patients told us that they saw an important role for themselves in their own care. They repeatedly used phrases like "I know my own body best" and "I trust my own judgement most". A chiropractic patient who had experienced a bad fall told us:

The doctor was giving me drugs to kill the pain but I knew the fall had shook up my whole system; it had to. I could see that the problem was getting worse again; I could see that for myself. So I decided to go to a chiropractor.

A woman Reiki client with melanoma maintained that:

After three years of this I'm much more experienced about it than the doctors. I have made it clear to the doctors that I do not want surgery. I decided not to have an operation; when you take on the responsibilities for your own health, you also take on the consequences and I can handle them.--I have chosen my alternative practitioners carefully; they all have degrees.

A female patient who was suffering from depression was seeing a naturopath. She said :

I went to a doctor when I had my problem and I discussed it with him. He said that it was because I had reached menopause and a lot of women my age feel depressed. I said that I didn't believe him. I told him that I'm depressed because I don't feel well and you can't tell me otherwise, and he argued with me. So I got up and left. --------You have to be in tune with your body and your body tells you what to do, you know, what it can handle and what it can't.

Partners and Friends

Alternative patients frequently described the relationship with their practitioners as a partnership. A naturopathic patient who had a heart attack said:

We really work as partners. Partnership is best because it means we can share knowledge and make decisions together. The cardiologist I saw earlier told me I didn't have a problem and when I questioned him, he told me that he was never wrong about these matters. He was very paternalistic and I didn't go back.

A few alternative patients who had been going to their practitioners for a period of a month or more characterized their therapists as friends. A patient with emotional problems who was consulting a Reiki practitioner told us:

I was very lucky to get in to see her and she has become a constant friend. She is a generous person, with good intuition as to what is going on in you head. Her treatment is very personal and yet she doesn't play mind games with you like psychiatrists do. You feel that you are talking with a friend.

This was not the way patients of family physicians depicted their therapeutic relationships. Rather, they described their physician in more utilitarian terms as demonstrated by a female patient with digestive problems :

She is a really good doctor with lots of experience. I wanted a young doctor who will outlive me and was conveniently located -- I know that my doctor is someone who will set me straight.

Explaining Egalitarian Relationships

The more egalitarian relationship described by alternative patients seemed to result from several factors. The most obvious is the frequency of visits; the initial treatments for most alternative therapies involve regular and frequent appointments with the practitioner until the condition is under control. In the past, 68% of the alternative patients saw their practitioners a few times a month or more (compared to 11% of the family physician patients). By comparison when exploring current use the frequency of visits decreases somewhat for the older alternative patients and increases for the patients of family phsyicians. Half (50%) of the alternative patients report visiting their practitioners a few times a month or more compared to 20% of the family physician patients. Overall, patients of alternative practitioners consult with their practitioners on a more frequent, steady basis. During the course of these frequent treatments, it is not surprising for patients to develop strong personal ties with the practitioner, especially if the encounters take place in the alternative practitioner's home or in office settings that are usually less formal than the doctor's office (Boon, 1996).

A second factor is the intimate style of interaction involved in alternative treatments. Many alternative therapies, such as chiropractic, acupuncture and Reiki require that the practitioner physically touch the body of the patient during treatment, thus creating a sense of closeness. In addition, the holistic approach typical of alternative care requires comprehensive knowledge of personal and life-style details including marital satisfaction, family situation, social life, career pressures and the like. As Kane at al (1974;1336) observed decades ago:

The chiropractor may be more attuned to the total needs of the patient than is his hurried medical counterpart....He uses language that the patient can understand. He gives them sympathy, he is patient with them. He does not take a superior attitude toward them.

Gaining this kind of contextual information demands consistent, in-depth and open communication between patient and practitioner. This can only happen if the practitioner is willing and able to spend considerable time with patients and is prepared to listen carefully to what Mishler (1984) calls the "voice of the lifeworld", as contrasted with the "voice of medicine". As a naturopathic patient recalled:

The sessions with him when 1 first started were like two hour sessions. I mean he took notes; he wrote a book on me. ----- Oh yeah, they do a history on you like you wouldn't believe. He wanted to know all about me and my life and what I was thinking and feeling.

A third reason alternative patients tend to regard their practitioners as friends or partners is that the nature of most alternative therapies requires that patients take responsibility for their own care. Alternative practitioners expect their patients to pay attention to their diet, posture, sleep patterns, exercise regimens, stress reduction and other aspects of their lives, long after they leave their practitioner's office. In accepting this responsibility, patients enter into a partnership relationship with their practitioner and work together with him/her to improve their health, tracing their daily routines step by step in order to identify problems and develop coping strategies. This approach helps to break down barriers between the therapist and the patient and to promote a more collegial connection. A female Reiki patient reported:

When I first went to a homeopath, he encouraged me to read books on homeopathy, nutrition and herbs and I learned a great deal. He always answered my questions and seemed to take an interest in my reading. We would discuss it when I had questions about it.

Trust

Another consideration that has been identified as crucial to the therapeutic relationship is trust (Horder 1994). Are there differences between the two groups of patients in the way they regard the importance of trust in their relationships with their practitioners?

In the case of family physician patients, the most important aspect of the therapeutic relationship they mentioned was the trust they placed in their physicians. They believed that their doctors had good diagnostic skills, useful tests and effective medications and expressed confidence that they were being scientifically monitored for illnesses. Many of these patients had built up long term relationships with their physicians, seeing them over many years. A male patient who was being monitored by his family physician after heart surgery reported that he had been seeing this doctor for over twenty-five years and before that, he had been consulting his predecessor for about twenty years. The length of the therapeutic relationship had the effect of reinforcing the confidence these patients had in their doctors. A female patient who was consulting her family physician for a virus condition told us that she finds him "caring and understanding" as well as skillful and that he has helped her through a number of different medical crises. One woman who had not as yet been helped with her problem of severe diarrhea, told us:

So far, the doctor hasn't been able to help me at all, but I find that just seeing her is very reassuring. I chose her because 1 thought she was competent and I am sure she will solve the problem.

Another woman who had high blood pressure said:

I have never had any inappropriate treatment or misinformation from a doctor, so I am very trusting of my physicians. I have a strong belief in the medical system because I've had only good experiences so far. My doctors have known what was needed.

A young woman who was suffering from panic disorder was recommended to her family physician by her boyfriend and his sister who had been consulting him for a long time. She told us:

He gives me great advice. I am sure that he is the one who can help me because I trust him completely. So far, I am not seeing much improvement but I have confidence that Dr. X will see me through this crisis.

In contrast, alternative patients were far less likely to use language that emphasized the trust they placed in their practitioners. While they may indeed have had confidence in them, they tended to speak most often about the faith they placed in their own instincts and knowledge of their bodies. As a male acupuncture patient with a sports injury told us:

I'm always trying to analyze, you know, what's happening now, and am I doing the right thing. I'm not lying back and letting this beat me. I'm using my brain to help me recover.

A female naturopathic patient who suffered with allergies put it this way:

It's a matter of knowing yourself, and your body; you are used to it.---- It tells you what it can handle and what it can't. You have to listen to it and you have to let your practitioner know how you are feeling.

It seems likely that the different kinds of health problems the two sets of patients were presenting to their practitioners had an effect on the issue of trust. The acute or more life-threatening illnesses experienced by many of the patients of family physicians made them more dependent on their doctor for accurate diagnosis, effective treatment and careful monitoring. The question of expertise becomes paramount when a health problem is seen as dangerous and possibly fatal. Patients need to feel that they can trust their physician to use all the scientific measures available and to believe that the doctor is working in their best interests. (Beauchamp and McCullough 1984).

Attention and Time

It is not surprising, given the emphasis on a holistic approach, that the patients in the study who were consulting alternative practitioners did not complain of lack of personal interest or time spent with them. But surprisingly, in view of the literature cited above, neither did the patients who were seeing their family physicians. This finding makes it clear that in spite of recent reports that family physicians are too insensitive, evasive and pressured to give good care (Phillips 1996), the reality is much more complex.

Negative comments about physicians were made, however, by alternative patients who had previously been consulting family physicians for their primary health problems. They explained that one of the major reasons they had turned to alternative practitioners for their particular problem was because they were not happy with the care they had received from their family physicians. They reported that they felt that they were being treated in standardized ways that were not tailored to their specific situation. In this connection they mentioned such measures as referrals to medical specialists, programmed prescriptions for drugs, a battery of tests and/ or the advice to "learn to live with the condition"'. For example, a female chiropractic patient said:

When I first had trouble with my back, I went to my family physician. He told me to stay in bed flat on my back until I felt better. After the second day, I was totally fed up; I knew I couldn't go on like that. When my friends suggested their chiropractor, I decided to try him instead. It had to be a better route to go than just lying there.

Many also protested that they were being rushed through their medical visit, without sufficient time to ask questions, gain needed information, and discuss the ramifications of the prescribed treatments. A male Reiki patient said he had recently seen his family physician for help with pain and infection.

She just prescribed regular penicillin. It did not do the job. When I made suggestions , she didn't like it. Most doctors don't like people who think --- it takes up time. She made it clear that she was the expert and that I should pay attention to what she was telling me.

Patient Satisfaction

Although the elements of trust, time and attention are important when considering the satisfaction that patients feel with their health care providers, there is clearly more involved. Satisfaction is an illusive concept, depending on the timing and nature of the healing encounter, the kind and extent of relief provided, and each patient’s hopes and expectations, It is important to note that both groups of older adults in our study reported high levels of satisfaction with the health care therapies and practitioners they were currently using. The vast majority (86%) of the patients of family physicians told us that their doctor had fully met their expectations and most (83%) alternative patients also felt that their expectations had been met fully by their practitioners. When considering this significant level of patient satisfaction, it is well to remember that each of the respondents was enlisted when he or she was actually making a visit to a practitioner. Patients who are dissatisfied usually stop coming for treatment and would not have been available for inclusion in our sample.

On the other hand, the health narratives indicated considerable dissatisfaction with previously seen practitioners (mainly physicians, but also some alternatives). Reasons for dissatisfaction related to their disappointment about how much help they could receive and also the way they were treated. They complained that their previous practitioners failed to listen to them sufficiently, treated them without respect, were too hurried, displayed a lack of interest in their particular situation and gave them pills rather than getting to the root of the problem. For example, a woman who was currently consulting a Reiki practitioner told us:

I went to see this neurologist; he was supposed to be so good, and I wrote down a list of the symptoms I had and everything.---He didn't even look at it. I was there all of five minutes.---He just handed the list back to me and was writing out a prescription for me, for nerves or something. I tore out of there and I tore up his prescription. He didn't even listen to my problem, you know.

A patient who was seeing an acupuncture/traditional Chinese doctor said:

I started going to a chiropractor and he snapped, snapped my neck and I was getting worse and worse. I stopped that and then went to a homeopath, and a massage therapist and someone who did shiatsu. They all helped at the start, you know, but then it kind of wore off. It's sort of like taking a sleeping pill, you take it for a long period of time and then all of a sudden it stops. But I haven’t found that with Dr. Y (her current acupuncture/ traditional Chinese medicine practitioner).

In their current healing encounters, however, both groups of older patients made it explicit that they were satisfied with the care they were receiving for their primary health problems. Just over three quarters said they would recommend the therapy they were receiving to family and friends. They were particularly enthusiastic about the practitioners that were giving them the therapies; 86% of the family physician said they would recommend their doctors and almost all of the alternative patients (96%) said they would be glad to recommend their practitioners.

In sum, both sets of older patients reported satisfaction with their practitioners and the care they were currently receiving, although their satisfaction was based on different criteria.

DISCUSSION

This study has examined the nature of the therapeutic relationship experienced by two groups of older adults; those who used conventional medical services for their primary health problems and those who chose to use alternative forms of health care. We have compared and contrasted the experiences of family physician patients with those of alternative patients and have found some consequential differences between the two groups.

Older Versus Younger

We found that older adults generally prefer to consult family physicians for their primary health problems and that only a small number of them choose to use alternative practitioners. Older adults have had a lifetime of consulting medical experts and most seem content to continue relying on conventional medicine to help them with their problems. As Irish (1997) has pointed out, older adults hold values that encourage them to maintain a more traditional passive role. In addition, it seems that finances may play a role in their reluctance to consult alternative practitioners; those older adults who are no longer employed are likely to have less disposable income to pay for health care which is not state supported.

This pattern contrasts sharply with the attitudes and behavior of younger people in Canadian society today. The most recent Canadian data (CTV/Angus Reid Group 1997) indicates that those under 55 years of age are much more likely to have used alternative care in the past five years than people who are 55 and over (146% growth in use over the past five years for Canadians aged 18 to 34; 76% growth among Canadians aged 35 to 54, and 49% growth among Canadians aged 55 years and older). Kelner, Wellman and Wigdor, (1996) also found that people under 55 were considerably more likely to use alternative forms of care. In keeping with current beliefs about the desirability of having more "choice" over one's health and illness, younger people are taking a more active role in their care and expect to have more collegial relationships with their practitioners. Alternative practitioners provide an approach to care which typically fits these expectations. When the baby boomers reach the age of 55 and start to develop persistent health problems, they are likely to be more experienced with and receptive to use of alternative modes of care.

Medical Versus Alternative

Some of the older adults in the sample did, however, choose to consult alternative practitioners for their primary health problems. What distinguished these patients from the rest? First, they were better educated, more informed and more affluent. Second, they had fewer life-threatening health problems. Third, they preferred tp have more control over the choices and decisions affecting their heath care, believing that because they knew their own bodies best, their opinions should be influential. Finally, they expressed a stronger sense of responsibility for their own health and health care.

Coward (1990) suggests that the sense of personal responsibility stems from the new conception of health as a state of well-being which goes far beyond the symptom-based definition of health espoused by medicine. Well-being is a state which can only be achieved if the individual is prepared to work at it through exercise, diet and other kinds of self-discipline. The alternative patients in this study supported this newer view of health.

Their distinctive beliefs have implications for the nature of the therapeutic relationship. This relationship was reported differently by the two groups. The alternative patients typically referred to "friendship" or "partnership" as the basis for their relationship with their practitioners, whereas the patients of family physicians spoke of the "trust" they felt in their physicians' skills and treatments. This is an important distinction, highlighting the personal responsibility felt by alternative patients for their own health, and contrasting this with the more deferential attitudes expressed by the older patients of family physicians. This difference does not imply, however, that one group of patients had a better relationship with their practitioner than the other; both were valued by patients and may have had a significant role in the healing process--- they were just different.

This finding should help to explode the common stereotype that it is only alternative practitioners who have good relationships with their patients and that this positive relationship is the principal reason they are able to help (Ernst, 1995). It is true that within the fee for structure health care system characteristic of North America, many physicians feel constrained by financial considerations to keep their encounters with patients relatively short, and that this pressure often has a negative effect on the therapeutic relationship. While some alternative practitioners may also see their patients for short periods, this typically happens only after they have spent enough time with them to become familiar with their case and the psycho-social context of their problems. It may also be that when people pay for health care out of their own pockets, as do alternative patients, they expect more time and interest and thus demand longer encounters with their practitioners. In spite of the shorter visits, however, and the constraints this places on personal intimacies, most of these older adult patients report positive relationships with their family physicians, even though the nature of the relationship is different.

One of the things that emerges from this analysis of the two groups is a picture of multiple use. Most alternative patients had not abandoned conventional medicine. Even those who expressed disillusionment with previously consulted physicians were still seeing their family physicians and as Sharma (1995) found, would probably resort to conventional medicine if they developed acute infections and injuries in the future. Different avenues for care were being used, either sequentially or concurrently by these older adults depending on their assessments of what would help most, what they could afford and what was available to them. Thus we see that important though it may be, the nature of the therapeutic relationship does not fully explain the use of a specific type of health care.

What other explanations may account for the choice of alternative forms of care? One obvious rationale relates to the finding that the older adults who were using alternatives had higher socio-economic status (SES) than those consulting family physicians. It can be argued that it is easier for alternative patients to find the money to pay for their therapies and that is why they decide to try other types of health care. It can also be argued that higher SES groups are generally acknowledged to be more “self-directed” (Kohn 1977). This orientation suggests that people of this status would be more likely to explore non-conventional types of health care. Another view holds that higher SES groups have a taste for a greater variety of forms of culture. People with more education or higher level jobs consume almost every kind of culture at higher rates (Erickson 1996). Treatment modalities can be seen as one more choice from the cultural menu.

A different kind of explanation focuses on the influence of the specific situation. When people are suffering from illnesses which make them fearful for the consequences, they are likely to want an authoritative expert (i.e. a physician) for help. Less alarming health problems may encourage people to be open to other options. Furthermore, when patients decide to consult an alternative practitioner they view them in a different way than they see doctors (i.e. not as scientific experts) and as a consequence are likely to treat them in a more egalitarian fashion.

Finally, studies have shown that an overwhelming majority of alternative patients turn to non-conventional therapies because they have become dissatisfied and frustrated with conventional medicine (Furnham and Smith 1988; Kelner and Wellman 1997). They feel they have nothing to lose and believe that alternative therapies can do them no harm. Consequently, they are prepared to “give them a try”.

It is clear that motivations to use alternative care are complex. Some combination of all these explanations will undoubtedly provide a fuller understanding of the current popularity of alternative health care. Among these factors it is important to recognize the influence of the distinctive therapeutic relationship experienced by patients and alternative practitioners. We know that there is an association between the kind of care that alternative practitioners deliver and the attraction to alternative therapies. What we do not yet know is the extent of this influence and where the nature of the therapeutic relationship fits in the overall picture.

REFERENCES

Beauchamp, T., and L. McCullough. 1984. Medical Ethics: The Moral Responsibilities of Physicians. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Blaxter, Mildred, and E. Patterson. 1982. Mothers and Daughters:A Three Generational Study of Health Attitudes and Behaviour. London: Heinemann Educational Books.

Boon, Heather. 1996. “Canadian Naturopathic Practitioners: The Effects of Holistic and Scientific World Views on their Socialization Experiences and Practice Patterns.” Pp. 260 in Faculty of Pharmacy. Toronto: University of Toronto.

Brody, Elaine M. 1985. Mental and Physical Health Practices of Older People. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

Brody, Howard. 1987. Stories of Sickness. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Brody, Howard. 1991. The Healer's Power. New Haven: Yale Univeristy Press.

Cassidy, Claire M. 1998. “Chinese Medicine Users in the United States Part 1: Utilization, Satisfaction, Medical Plurality.” The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 4:17 - 27.

Chappell, Neena L. (Ed.). 1987. The Interface Among Three Systems of Care: Self, Informal, and Formal. New York: Springer Publishing Co.

Cohen, G. 1996. “Age and Health Status in a Patient Satisfaction Survey.” Social Science and Medicine 42:1085-1093.

Coward, R. 1990. The Whole Truth. London: Faber and Faber.

Denzin, NK , and YS Lincoln (Eds.). 1994. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Erickson, Bonnie. 1996. “Culture, Class, and Connections.” American Journal of Sociology 102:217- 251.

Ernst, Edzard. 1995. “Placebos in Medicine.” Lancet 345:65.

Furnham, Adrian, and Chris Smith. 1988. “Choosing Alternative Medicine: A Comparison of Health Beliefs of Patients Visiting a General Practitioner and a Homeopath.” Social Science and Medicine 26:685-689.

Gevitz, Norman (Ed.). 1988. Other Healers: Unorthodox Medicine in America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins.

Greene, M. G., R.D. Adelman, E. Friedmann, and R. Charon. 1994. “Older Patient Satisfation with Communication During an Initial Medical Encounter.” Social Science and Medicine 38:1279- 1288.

Hafferty, Federic W., and Donald W. Light. 1995. “Professional Dynamics and the Changing Nature of Medical Work.” Journal of Health and Social Behaviour :132-153.

Hafferty, F.W., and J.B. McKinlay (Eds.). 1993. The Changing Medical Profession. New York: Oxford University Press.

Haug, Marie R. 1994. “Elderly Patients, Caregivers, and Physicians: Theory and Research on Health Care Triads.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 35:1-12.

Haug, Marie R. , and Bebe Lavin. 1983. Consumerisim in Medicine: Challenging Physician Authority. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Horder, J. 1994. “The Historical Perspective.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 87:6 - 8.

Irish, J.T. 1997. “Decciphering the Physician-older patient interaction.” Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 27:251-267.

Kane, R. L., . D. Olsen, C. Laymaster, F.R. Woolley, and F.D. Fisher. 1974. “Manipulating the Patient: A Comparison of the Effecttiveness of Physician and Chiropractor Care.” The Lancet 1:1333-1336.

Katz, Jay. 1984. The Silent World of Doctor and Patient. New York: The Free press.

Kelner, Merrijoy, and Beverly Wellman. 1997. “Health Care and Consumer Choice: Medical and Alternative Therapies.” Social Science and Medicine 45:203-212.

Kelner, Merrijoy, Beverly Wellman, and Blossom Wigdor. 1996. “Health Care Choices of Older Adults.” Paper presented at the Canadian Gerontological Association. Quebec City, Quebec.

Kohn, Melvin L. 1977. Class and Conformity; a Study in Values. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Krupat, Edward, Julie T. Irish, Linda E. Kasten, Karen M. Freund, Risa B. Burns, Mark A. Moskowitz, and John B. Mckinlay. 1999. “Patient Assertiveness and Physician Decision-Making Among Older Breast Cancer Patients.” Social Science & Medicine 49:449-457.

Lewis, J. Rees. 1994. “Patirnt Views on Quality Care in General Practice: Literature Review.” Social Science and Medicine 39:655-670.

Lupton, Deborah. 1997. “Consumerism, Reflexivity and the Medical Encouter.” Social Science and Medicine 45:373-381.

McGregor, Katherine J. , and Edmund R. Peay. 1996. “The Choice of Alternative Therapy for Health Care: Testing Some Propositions.” Social Science and Medicine 43:1317-132.

McGuire, Meredith. 1988. Ritual Healing in Suburbnan America. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Mechanic, D., and M. Schlesinger. 1996. “The Impact of managed care on patients' trust in medical care and their physiciancs.” Journal of the Americam Medical Association 275:1693-1697.

Mishler, E.G. 1984. The Discourse of Medicine: Dialetics of Medical Interviews. Norwood: Ablex Publishing Company.

Morgan, David L. 1993. “Qualitative Content Analysis: A Guide to Paths Not Taken.” Qualitative Health Research 3:112-121.

National Advisory Council on Aging. 1997. “Alternative Medicine and Seniors: An Emphasis on Collaboration.” Ottawa: Government of Canada.

Parsons, Talcott (Ed.). 1951. The Social System. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

Phillips, Daphne. 1996. “Medical Professional Dominance and Client Dissatisfaction.” Social Science and Medicine 42:1419-1425.

Reid, Angus. 1997. “User Profile, Reasons for Using Alternative Medicines and Practices, Health Care Responsibility.” Toronto: CTV/Angus Reid Group Poll.

Rogers, D. 1994. “On Trust: A Basic Building Block for Healing Doctor- Patient Interactions.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 87:2-5.

Sharma, Ursula. 1992. Complementary Medicine Today: Practitioners and Patients. London: Routledge.

Sharma, Ursula. 1995. Complementary Medicine Today: Practitioners and Patients, revised edition. London: Routledge.

Szasz, Thomas S., and marc H. Hollender. 1956. “A Contribution to the Philosophy of Medicine: The Basic Models of the Doctor-Patient Relationship.” American Medical Association: Archives of Internal Medicine 97:585-592.

Thomas, Kate J. , Jane Carr, Linda Westlake, and Brain T. Williams. 1991. “Use of Non-orthodox and Conventional Health Care in Great Britain.” British Medical Journal 302:207-210.

Waitzkin, Howard, Theron Britt, and Constance Williams. 1994. “Narratives of Aging and Social Problems in Medical Encounters with Older Persons.” Journal Of Health and Social Behavior 35:322-348.

Weil, Andrew. 1995. Spontaneous Healing. New York: Fawcett Columbine.

|

|