![]()

-

WHO SEEKS ALTERNATIVE HEALTH CARE?

A Profile of the Users of Five Modes of Treatment

Merrijoy Kelner, Ph.D. and Beverly Wellman, M.Sc.

Patterns of health care utilization have received considerable attention from scholars (Anderson,1995; Mechanic, 1982; Pescosolido and Kronenfeld, 1995). In almost every case, the focus of research has been on conventional medical care; while other forms of health care utilization have received scant concern. This is in spite of the growing evidence that people in North America and Europe are using complementary or alternative forms of health care in increasing numbers (Eisenberg, 1993; Sharma, 1992; Coulter, 1985; Saks, 1992; Berger, 1993; Ernst, 1995a; Vincent and Furnham, 1996).This paper reports on research conducted in a large Canadian city during 1994-95. It compares the social and health characteristics of patients of family physicians (used as a base line group), chiropractors, acupuncturists/traditional Chinese medicine doctors, naturopaths and Reiki practitioners, in order to examine which characteristics differentiate the users of the various types of care. We explore the influence of age, gender, education, employment, occupation, income, religion, and ethnicity. Similarly, we look at the kind and severity of health problems, perceived health status, and how difficult it is to pay for treatment.

The key questions posed here are: (1) whether alternative patients differ from medical patients in their demographic characteristics, health problems and health opinions? We also ask (2) whether there are differences between the various types of alternative patients in demographic characteristics, health problems and health opinions?

These questions are particularly interesting in Canada where the Canadian health care system provides universal coverage for medical care. People who use alternative modalities must pay out of their own pockets. The sole exception is users of chiropractic services who receive small reimbursements from government. Thus, people who venture beyond the medical system are not making neutral decisions. If they remain within the system they are assured that their health care costs will be covered by government insurance and if they go elsewhere they must be prepared to bear the costs of their care.

Defining Alternative Medicine

There is still no consensus on how to describe non-medical health care. The concept of alternative medicine covers a diverse set of healing practices. The common thread is that they do not focus solely on biomedical processes nor do they fit under the scientific medical umbrella (Berliner and Salmon, 1980; Hayes-Bautista, 1977; Levin and Coreil, 1986; Roebuck and Hunter, 1972). While the form and content of each is quite different, most alternatives share underlying concepts of how the body works (Gevitz, 1988). Alternative therapies tend to emphasize the integration of body, mind and spirit and regard disease as having dimensions beyond the "purely biological" (Berliner and Salmon, 1979).

The two terms most frequently used are 'complementary' medicine and 'alternative' medicine. Those who describe non-orthodox health care as complementary essentially view it as an adjunct to medical care. The term itself implies the possibility of co-operation with orthodox medicine (Sharma, 1992). The concept of alternative medicine, on the other hand, focuses on the socio-political marginality of non-orthodox care. It highlights the fact that it stands on the edges of the established health care system and receives almost no support from the medical establishment or the government (Saks, 1992a). While we recognize that this debate is far from resolved, we have adopted the term "alternative health care", in this paper, to describe the treatments given by non-medical practitioners. This nomenclature reflects the fact that at least some of the modalities in our study have not been recognized by orthodox medicine.

The Development of Research on Users of Alternative Therapies

What kinds of people use alternative health care and what kinds of problems do they have? Researchers in North America, The UK, Germany and Australia have shown that alternative health users are typically found in large urban centres, and mainly tend to be women, middle aged, well educated, working in higher occupational and professional groups and earning good incomes. The health problems that prompt people to seek alternative therapies are typically chronic conditions like musculoskeletal problems and headaches, rather than acute or life-threatening illnesses.[1] The research shows that people also consult alternative practitioners for purposes of health promotion and maintenance (Kelner et al, 1980; Coulter, 1985; Berger, 1993; Wellman, 1995; Eisenberg, 1993; Thomas, 1991; Sharma, 1992; Vincent et al, 1995; Ernst, 1995b, Furnham and Forey, 1994; Furnham and Beard, 1995; McGregor and Peay, 1996).

We expand upon the findings reported above by presenting a profile of three hundred people who have used one of five types of health care. We systematically selected these five kinds of care to represent a broad spectrum of the many kinds of health care services currently available in North America. The therapies were selected to represent a range that moves from conventional medical care (family physicians) through physical manipulation (chiropractors) and mixed holistic care (acupuncture/traditional Chinese medicine and naturopathy) to care directed primarily at emotional and spiritual healing (Reiki). The spectrum moves from the alternative that is the most legitimate and widely accepted (chiropractic), to one of the most unconventional, least well known and least institutionalized (Reiki). We begin by providing a brief description of each modality.

The Five Treatment Modalities

Family medicine focuses on the provision of comprehensive and continuing primary care to individuals and their families. The term 'family physician' is used interchangeably in Canada with the term 'general practitioner'. Family physicians deal mainly with chronic, emotional and transient illness, in contrast to acute or life-threatening illnesses. Important aspects of their mandate are prevention and health promotion. Family physicians play the role of gatekeeper in the Canadian health care system; they are the ones who recommend patients to medical specialists.

Chiropractic is a system of manipulation of the spine and the joints. It is based on the view that maladjustments of the vertebrae interfere with the healthy operation of the nervous system. Advice about diet, posture and exercise is frequently included as part of chiropractic treatment. No drugs, medicines or surgery are used. Chiropractors have their own professional training college and regulatory bodies. Practitioners must train for at least four years and must be licensed by self-governing chiropractic agencies.

Acupuncture works on the theory that meridians, or energy channels, link inner organs to external points of the body. Treatment involves the application of fine needles at external points along these meridians, in order to stimulate healing. Many acupuncturists in North America, and particularly the ones who provided patients for this study, also practice traditional Chinese medicine, using herbal remedies based on ancient Chinese healing practices. Acupuncture/ traditional Chinese medicine has an academy in Canada, but no official college

Naturopathy is based on the theory that therapy should mobilize the body's inherent capacity to heal itself. Imbalance within the body, particularly an accumulation of toxins, is seen as the major cause of illness. Treatment focuses on the whole person and may include a wide range of therapies such as herbs, dietary adjustment, additional nutrients, fasting and exercise. Naturopathy now has its own Canadian college and regulatory body. Practitioners train for four years in the basic sciences and also in the use of various alternative therapies.

Reiki healing emphasizes the importance of the mind-body-spirit connection. Therapy consists of hands on, non-invasive techniques which make use of "universal life-force energy" to reduce stress, to improve overall well-being, and to deal with emotional and other problems. Clients take an active role in their own healing and frequently seek better self- understanding through the experience of healing. Reiki has no institutionalized training program or official association in Canada.

These five treatment modalities formed the basis of our research design. We used a sampling strategy which required a number of stages; identifying, selecting and contacting practitioners and patients from the treatment modalities.

METHODS

Accrual of Practitioners

In the the first stage, we randomly selected four practitioners from each of the five treatment modalities (5 X 4 =20). The selections were made from professional listings obtained from each of four practitioner associations. In the case of the fifth group, Reiki, which does not have a formal association in Canada, we sampled randomly from local listings in alternative directories. In cases where practitioners felt they were too busy, or did not have sufficient numbers of patients, further random sampling was used to contact new practitioners. Each randomly selected practitioner was sent a letter asking them to participate in the study. This was followed by a telephone call and a brief meeting.

Accrual of Patients

Once the practitioner agreed to take part, we requested that they randomly select 15 patients from their appointment book for a given day, or a series of days, until the required number was reached. Practitioners were used to select the patients in order to minimize rejection and also to give due respect to the relationship between practitioner and patient. We provided each practitioner with letters to give patients. The letter described the study and assured patients that whatever their decision regarding participation in the study, it would in no way affect their care. When a patient agreed, the practitioner gave us the name and phone number and we contacted them to set a date and time for an interview. We did not inform the practitioners which of their patients declined to be interviewed. Inclusion criteria for the patient sample were that: (1) they be eighteen years of age and over, (2) they speak English fluently enough to sustain a long interview, and (3) and they be in sufficiently good health to participate. In sum, our data come from 300 patients (15 X 4 X 5 = 300). A limitation of the study is that we were not in a position to ensure that all practitioners followed the research protocol exactly as we outlined it..

Data Gathering and Analysis

Three hundred adults were interviewed in person about their use of health care services within the past year (1994-95). The semi-structured interviews were recorded by hand and also by tape, and lasted an average of one hour. Interviews were conducted at the patients' homes, their places of work, at our offices, or in coffee shops, but never on the practitioners' premises.

We asked patients to tell us about the primary health problem that brought them to seek care from the practitioner in whose office we had contacted them. In order to minimize selective recall of events and information, we focused in detail on the most recent incident that had brought them to treatment. To analyze these health narratives, we used qualitative methods including content analysis and constant comparison (Strauss and Corbin, 1990). In addition, we collected information on socio-demographic characteristics such as age and gender, attitudes about their health, how they paid for their treatment and whether they were consulting other kinds of health care practitioners. We chose a sample of 300 patients in order to meet the criteria for using multivariate statistical analysis. Responses to the interview schedule were coded and entered into SPSS/pc for quantitative analysis. We used analysis of variance to examine statistically significant differences between the five groups of patients.

In the following profiles, we assemble a descriptive portrait of the five different patient groups, using only the quantitative data appropriate for such an analysis.

RESULTS

As we have categorical measures of the social characteristics and health characteristics of the patients, we use chi-square to identify (at the .05 level) if there are significant differences overall in the five treatment groups and Cramer’s V to show the strength of association between the five groups and the social and health characteristics variable. (For the one continuous variable, age, we use one-way ANOVA.)

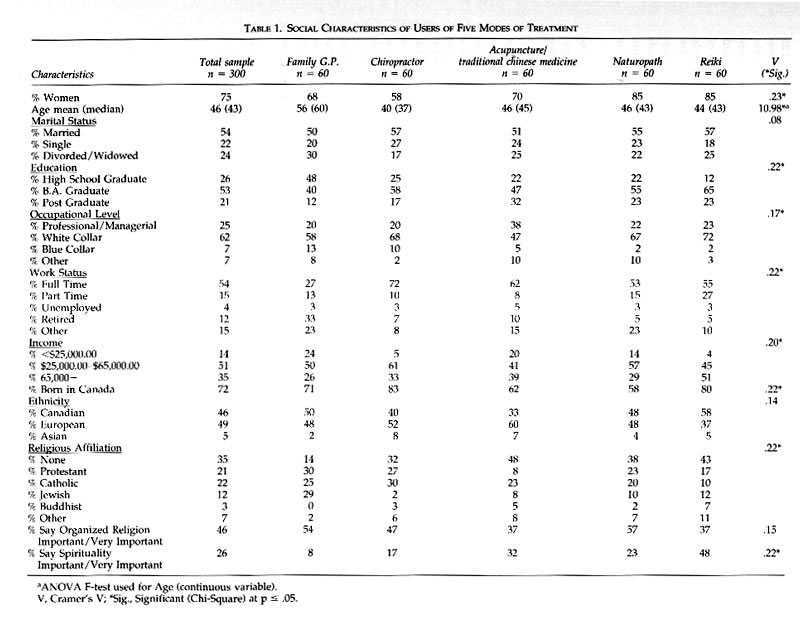

Almost all of the social characteristics studied vary significantly by treatment group (Table 1): gender, age, education, occupational level, work status, income, Canadian birth, religious affiliation and spirituality. The strengths of association for these variables are moderate, with Cramer’s V showing between .20 and .23 for most. The strongest association is .23 for gender while the lowest significant association is .17 for education. The only social characteristics not significantly associated are marital status, ethnicity and orientation to organized religion. In short, these groups vary significantly in gender, age, socioeconomic status, religion, Canadian birth and spirituality.

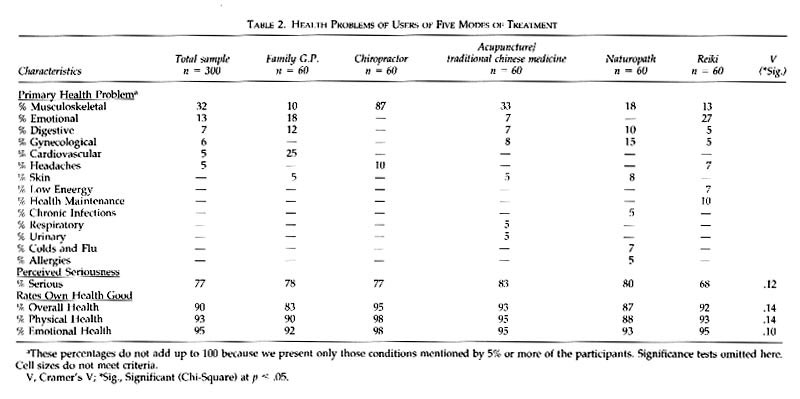

There are no significant differences in the health characteristics of the patients of the five treatment groups for almost all rate their own health at least as “good” (last three rows of Table 2). Table 2 shows much variation in the primary health problems of the five groups, but small cell sizes preclude statistical testing.

Despite the possibility that practitioners did not always select patients for the study on a completely random basis, nevertheless, the use of four practitioners in each treatment group reduces selection biases. However, the sampling limitations suggest caution in generalizing from our findings to the general population of health care users.

Patients of Family Physicians

Social Characteristics: When we analyze the social characteristics of the 60 patients of family practitioners, we find that there are more than twice as many women (68%) than men (32%). This higher percentage of women seeing family physicians reflects the general tendency for women to seek health care more often than men (Nathanson, 1984). The ages range from 23 to 88 with a mean age of 56 years and a median age of 60; this makes them considerably older (approximately 10 years) than the patients of the other treatment groups (Table 1). Based on the results of one-way analysis of variance (Scheffe test), this difference is statistically significant (F=10.98, P<0.05; Table 1).

The patients of family physicians have the lowest percentage of people graduating with a Bachelor of Arts degree (40%; Table 1): a statistically significant difference when compared to patients of acupuncture/ traditional Chinese medicine, naturopathy and Reiki (Table 1). The family physician patients are more apt to be blue collar workers (13%) than are the patients of the other groups. They also report household incomes that are somewhat lower than the other groups and significantly lower than the Reiki group. Fewer of these patients are employed in full-time work (27%) and many are retired (33%).

Toronto is a pluralistic, urban centre, where many ethnic groups co-exist. Canadian identity is complicated by the fact that the country has a definite policy of multiculturalism, which encourages the retention of peoples' original ethnic identities. Although almost three quarters (71%) of the patients of family physicians said they were born in Canada, only half (50%) of them describe themselves as Canadian, while 48% describe themselves as European and 2% as Asian (Table 1). There are significant overall differences between groups in the percentage reporting they have a religion affiliation, with patients of family physicians having the most affiliation (86%; Table 1).

Health Profile: The most frequently mentioned health problems that brought these patients to their family physicians were cardiovascular conditions such as heart problems, high blood pressure and high cholesterol (25%; Table 2). By contrast, none of the other patient groups reported cardiovascular conditions as their primary reason for seeking care. In addition, patients of family physicians presented a variety of other kinds of health problems, both physical and emotional, for care. There are differences in the kinds of health problems that patients present to their family physicians as compared to the patients of acupuncture/tcm, chiropractors, naturopaths and Reiki. Although slightly more than three quarters (78%) say they regard their primary health problem as serious or somewhat serious, an even higher percentage (83%) rate their overall health as good or average. There are no significant differences in these respects between the groups (Table 2).

In keeping with Canadian health care policy, all of the patients of family physicians report that they are fully covered by government health insurance.

Patients of Chiropractors

Social Characteristics: There is a more equal distribution of men (42%) and women (58%) among these patients than in the other four treatment groups. It is likely that more men seek chiropractic care because they are more frequently employed in jobs that require heavy lifting or other kinds of hard physical labour. The ages range from 20 to 82, with a mean age of forty (median, 37) and a majority of patients (60%) under forty. This is a somewhat younger age distribution than those in the other four treatment groups (Table 1).

These patients have a higher level of education than the patients of family physicians in the study. Over half (58%) have an undergraduate degree and 17% have some graduate training. While the occupational level of the chiropractic patients is similar to the patients of family physicians, they report higher household incomes: 33% report incomes of over $65,000. A higher percentage (72%) are in full time employment than the patients in any of the other groups.

Five-sixths of the chiropractic patients (83%) say they were born in Canada although only 40% describe themselves to be ethnically Canadian (Table 1). The rest describe themselves either as European (52%) or Asian (8%). With regard to religious affiliation, the most notable difference from the other groups is the low percentage of Jewish patients (2%) and the higher percentage of Catholics (30%).

Health Profile: Our data are congruent with other studies that have shown that people seek care from chiropractors for a narrow range of problems (Kelner et al., 1980; Coulter, 1989; Eisenberg, 1993). Eighty-seven percent of the chiropractic patients report their primary health problem to be musculoskeletal (Table 2). This statistically significant difference distinguishes the chiropractic group from all the others (Table 2). Most (77%) regard their health problems as serious or somewhat serious, yet 95% rate themselves as healthy overall and 98% regard their physical and emotional health as good or average (Table 2).

All chiropractic patients are partially covered for chiropractic treatments by government insurance. Some (38%) are covered completely by a combination of private insurance and government payments. Over half (59%) of those not fully covered say they find payment hard to make.

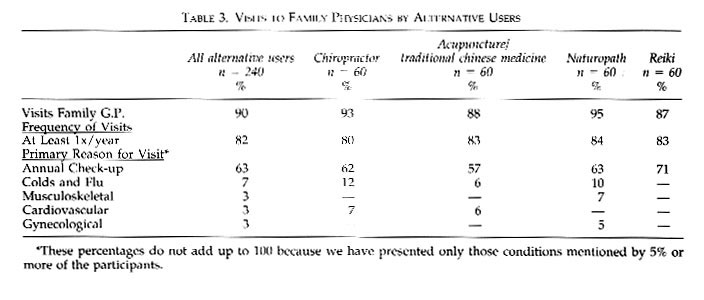

Almost all chiropractic patients (93%) also consult with family physicians. Eighty percent of these see their physician at least once a year while the rest say they consult only when the need arises. The main reasons given for visiting their family physician are health prevention and maintenance check-up (62%); colds and flu (12%; Table 3).

Patients of Acupuncturists/Traditional Chinese Medicine Doctors

Social Characteristics: Unlike patients of chiropractors, the majority (70%) of acupuncture/ traditional Chinese medicine patients are women. Their ages range from 24 to 74 years and the mean age is 46 years of age (median, 45). This is somewhat older than the group of chiropractic patients, but ten years younger than the patients of family physicians (Table 1).

Compared to the two previously discussed groups, more of these patients have university and graduate level education. Half (47%) have an undergraduate degree, and one-third (32%) have advanced graduate school training. Commensurate with their high level of education, many patients (38%) are in professional or managerial occupations. Their income level reflects their educational and occupational status; 39% report incomes of over $65,000. The majority (62%) are employed full-time (Table 1).

Although 62% of acupuncture patients were born in Canada, only about half (33%) describe themselves as Canadian with the remainder describe themselves as European (60%) and Asian (7%; Table 1). This percentage of Asian patients is low, considering that three of the four acupuncture/tcm practitioners in the study were Asian. This may reflect the study's requirement that participants be fluent in English, or it may signify that acupuncture/ tcm now has a broad appeal.

Almost half (48%) of these patients say they have no religious affiliation; the highest percentage of any treatment group in the study. Nevertheless, this group has an atypically high number of people (32%) who say that spirituality is an important factor in their lives. Among those who are religiously affiliated, 23% are Catholic, 8% are Protestant, 8% are Jewish, and 5% are Buddhist (Table 1).

Health Profile: The range of health problems for which these people use acupuncture/tcm is the widest of any group in the study, comprising 21 kinds of problems. The most frequently mentioned primary health problems are musculoskeletal (33%), gynaecological (8%), emotional (7%) and digestive (7%; Table 2). Five-sixths (83%) say that they consider their primary health problem to be serious or somewhat serious. Yet, as is the case for the other groups, almost all regard themselves as generally healthy (93%) and consider their physical and emotional health to be good or excellent (95%).

None of these patients are covered by government insurance for their acupuncture/tcm treatments. The vast majority (85%) have no coverage for acupuncture/tcm at all, while 15% have some sort of partial coverage such as motor vehicle accident insurance. Almost all (90%) say that it is hard or somewhat hard for them to pay for treatment but nonetheless, they are still willing to do so.

Seven-eighths of acupuncture/ tcm patients (88%) also consult a family physician for their health care and most of them (83%) see their physician at least once a year (Table 3). Health prevention and maintenance (annual check-up) are the main reasons they go (57%), followed by cardiovascular problems (6%), and colds and flu (6%).

Patients of Naturopathic Practitioners

Social Characteristics: There are significant differences in the percentage of women and men who go to each type of practitioner. Women constitute 85% of the sample of patients of naturopathic doctors (Table 1), a higher percentage than the three treatment groups already discussed.

Mean ages between groups also differ significantly (F=10.98, P<0.05). The nautropathic patients range in ages from 27 to 69 years. Almost half (46%) are in their forties with a mean age of 46 years (median, 43). This average is much younger than the patients of family physicians but no different than the other groups of alternative patients.

Naturopathy patients are well educated. Their level of education is similar to the patients of chiropractors and acupuncturist/ tcm doctors but significantly higher than the patients of family physicians. A substantial minority (22%) are in professional or managerial positions. Their income level is concentrated in the middle range. Over half (57%) earn incomes between $25,000 and $65,000, and work full-time .

Somewhat more than half (58%) of the naturopathic patients say they were born in Canada, and slightly less than half (48%) describe their ethnic group as Canadian (Table 1). Over one third (38%) have no religious affiliation, and nearly one quarter (23%) say they consider spirituality an important factor in their lives.

Health Profile: The primary problems for which these patients have consulted naturopaths encompass a wide range of everyday concerns such as colds and flu (7%), allergies (5%) and chronic infections (5%; Table 2). As 85% of these patients are female, it is not surprising that gynaecological troubles such as menopausal symptoms are reported (15%).

Although many of the complaints mentioned seem relatively benign, four-fifths of these patients (80%) consider their primary health problem to be serious or somewhat serious. This may be because these are long standing health complaints that have not responded well to treatment. Despite these complaints, 87% rate themselves as healthy overall, 88% rate their physical health and 93% rate their emotional health as good or average (Table 2).

Since government health care insurance does not pay for naturopathic treatments, none of these patients’ naturopathic expenses are covered by government insurance; 78% have no coverage whatsoever, while 22% have some sort of partial coverage such as motor vehicle accident insurance. Eighty percent of the naturopathic sample say they find it hard or somewhat hard to pay for their naturopathic treatments.

Almost all (95%) of the patients of naturopaths visit a family physician on a regular basis (Table 3). Among those who do so, 84% go at least once a year, mainly for health prevention and maintenance (annual check-up; 63%) and colds and flu (10%).

Clients of Reiki Practitioners[2]

Social Characteristics: Like naturopathic patients, the great majority (85%) of the clients of Reiki practitioners are women (Table 1). The ages range from 25 to 90, and the mean age is 44 years (median, 43).

Reiki clients are the most highly educated in the study. A majority (65%) have bachelors' degrees while another 23% have gone on to graduate school. Almost one quarter (23%) are in professional or managerial occupations. A number of these professionals/patients are themselves working as therapists, either as Reiki practitioners or in related fields such as massage or the Alexander Technique. Only 2% are in blue collar jobs; the Reiki group along with naturopathic group has the lowest percentage of people employed in such jobs. Reiki clients report the highest level of household incomes of any group in the study and this difference is significant (Table 1). Almost half of them (51%) earn incomes above $65,000. Many more clients than in the other treatment groups work in the arts or as alternative practitioners.

Similar to the chiropractic patients, a high percentage (80%) were born in Canada, and compared to the other groups, a relatively high percentage (58%) describe themselves as Canadian (Table 1). The rest describe themselves as European (37%) or Asian (5%). Similar to acupuncture/tcm patients, a substantial number of Reiki clients (43%) report having no religious affiliation. The rest identify themselves as Protestant (17%), Catholic (10%), Jewish (12%), Buddhist (7%), and a combination of other rare religions (12%) such as Eckankar. Nearly half of the Reiki clients (48%) stress the importance of spirituality in their lives, higher than the other treatment groups.

Health Profile: Reiki clients present an interesting contrast in terms of the reasons they seek care (Table 2). Slightly more than one quarter (27%) of Reiki clients report that it is principally for emotional difficulties and self-development that they consult their practitioners.This is consistent with the primary goals of Reiki healing to reduce stress and to deal with emotional problems. (Reiki practitioners also treat conditions such as chronic pain and asthma.) This percentage is considerably higher than for patients of family physicians, many of whom also seek care for emotional problems. Moreover, this is the only alternative group in which more than a few patients emphasize health maintenance and prevention (10%) as a reason to seek help. Compared to all other groups, a lower percentage (68%) consider their problems to be serious or somewhat serious. This lower assessment of seriousness reflects the fact that many seek out Reiki practitioners for health promotion and self-realization rather than for treatment. Most clients (92%) consider themselves to be healthy overall: 93% rate their physical health as good or average and 95% rate their emotional health as good or average.

None of these clients are covered by government insurance for their treatments, and 95% have no kind of insurance available to pay for Reiki. Most (82%) say they find it difficult to make these payments in spite of the fact that this group has the highest earnings in the Almost all (87%) of the Reiki clients visit a family physician for their health care. Most of these (83%) do so at least once a year, mainly for health prevention and health maintenance (annual check-up; 71%).

Patient Use of Multiple Therapies

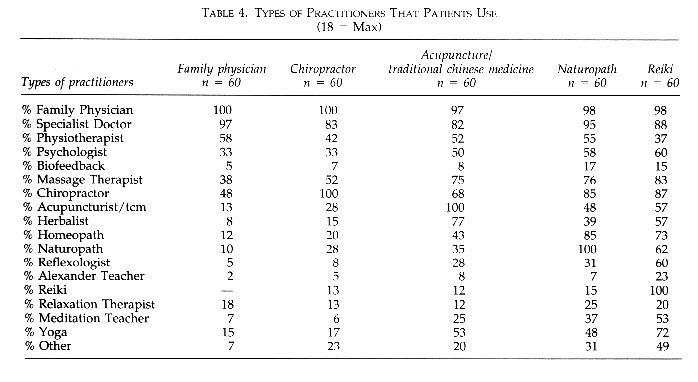

We have already established that almost all the patients in the five groups have also seen a family physician within the past year. An important question to consider is what other kinds of health care practitioners the patients in this study are consulting. We asked all 300 patients in our study whether they had ever consulted other kinds of health care practitioners. We presented them with a list of eighteen options, including the category of "other" to include some of the more esoteric therapies (Table 4). The findings show that patients of family physicians use only a few additional kinds of practitioners, mainly medical specialists (97%), physiotherapists (58%), chiropractors (48%), massage therapists (38%) and psychologists (33%). Patients of chiropractors show a similar pattern. In addition to family physicians, they have mainly seen medical specialists (83%), massage therapists (52%), physiotherapists (42%) and psychologists (33%).

The picture changes when we examine the use of multiple therapies among the other three groups of patients. Many acupuncture/tcm patients report that they have consulted a wide range of types of practitioners. Besides family physicians, over half of these patients have seen medical specialists (82%), massage therapists (75%), herbalists (77%), chiropractors (68%), yoga (53%), physiotherapists (52%), and psychologists (50%). Similarly, in addition to family physicians, over half of the naturopathic patients have consulted with medical specialists (95%), chiropractors (85%), homeopaths (85%), physiotherapists (55%), and psychologists (58%). As well, just under half (48%) of these patients have used yoga and acupuncture for their health care. The Reiki patients have consulted with more kinds of practitioners than any of the others. In addition to family physicians, over half have seen medical specialists (88%), chiropractors (87%), massage therapists (83%), homeopaths (73%), Yoga instructors (72%), naturopaths (62%), psychologists (60%), reflexologists (60%), acupuncturists, herbalists, and homeopaths (each 57%), and meditation therapists (53%). In addition, just under half of the Reiki patients (49%) report that they have used "other " kinds of health care practitioners.

These findings show that the patients of family physicians and chiropractors are considerably more conservative in their choices about which kinds of therapies to use for their health problems than are the other groups of patients. They stay mainly with conventional medicine or alternatives that work closely with physicians, such as physiotherapy and increasingly, chiropractic. Patients of acupuncture/tcm and naturopathy are more adventurous in their selection of treatment modalities, venturing beyond therapies that are associated with medical practice and consulting with practitioners who work with alternative models of healing such as homeopaths and herbalists. They tend to use more kinds of practitioners, more often. Reiki patients are the ones who are more apt to have tried different kind of therapies. More often than any of the others, they have consulted less well known or recognized kinds of practitioners such as Alexander teachers and reflexologists. They seem to be the kind of patients who continue to seek relief for their health problems, still hoping to find a solution.

DISCUSSION

Most studies of users of alternative health care have examined them as one homogeneous group. An exception to this trend is provided by the work of Furnham and his colleagues (1993) who found differences among three groups of alternative care users in selected demographic variables, certain aspects of their health problems, and in their health beliefs. The data presented here indicate that there are some interesting differences in the social and health profiles of the patients included in this study. Our study answers the two research questions posed at the beginning of this paper by showing that alternative patients not only differ from medical patients, but that there are also differences between the various types of alternative patients.

As we examine the different patient populations, we see that the most striking social and health differences occur between those who seek care from family physicians and the patients of alternative practitioners. People who use alternative care are more likely to be female, to have higher household incomes and education and to consider spirituality an important factor in their lives. They are less likely to be in blue collar occupations and to be religiously affiliated. The range of their health problems is greater and they tend to rate their physical and emotional health status higher. Since users of these therapies receive no government supported health insurance for their alternative care, many say they find it hard to pay for their treatments.

This gross comparison, however, misses some important nuances which differentiate each of the five groups. For example, when we look at the data provided by the chiropractic patients, we see that along several dimensions, they differ from patients of all the other groups. They are unique in that the number of males and females are almost equal; they are the most likely to be employed full-time, to be born in Canada, to describe themselves as European, and to be Catholic. In terms of their health problems, the range is narrow and specific, focusing almost exclusively on musculoskeletal problems and headaches. These patients receive partial reimbursement from government for their chiropractic treatments and accordingly, fewer report that they find the payments hard to make.

At the other end of the spectrum, the clients of Reiki practitioners present another kind of portrait. They have the highest level of education, are most likely to be employed in professional, managerial and white collar occupations and to report high household incomes. This group tend to work in creative and artistic fields and to stress the spiritual and emotional aspects of their lives. They seek care mainly for emotional problems, personal development and health maintenance. Accordingly, fewer of them rate their health problems as serious. They receive no government assistance or other kinds of insurance for their Reiki treatments but are prepared to pay out of their own pockets for this kind of treatment.

The profile of users of alternative modes of health care that emerges here is strikingly similar to the descriptions found in other studies. Most researchers who have analyzed the characteristics of people who use alternative practitioners have found that they earn higher incomes and are better educated than patients who use traditional medical care. Our study also confirms the view expressed by Furnham and Smith (1988) that patients select the type of practitioner they use depending on the their particular kind of health problem.

The analysis carried out in this study has several advantages over most studies of alternative users. First, the data permit us to present detailed descriptions of the patients using a variety of specific treatment modalities. Second, we are able to contrast the users of alternative treatments with patients who seek care from family physicians for their primary health problems. Finally, by selecting treatment modes along a spectrum of public recognition and institutional legitimacy, we are able to demonstrate that the differences between patients who use conventional medical services and those who use alternatives, become more pronounced as we move from the most institutionalized (family medicine) to the least institutionalized (Reiki).

The differences in social and health characteristics between the four alternative treatment groups underlines the hazards of lumping all alternative users under one umbrella. We know that their characteristics are different and this may mean that their motives for seeking alternative care are also different. This proposition will be explored in subsequent papers based on this research.

It is clear that a majority of users of alternative therapies also consult a family physician for their health care. They may have reservations about how much help they can get for their chronic problems, but they have definitely not lost confidence in the potency of conventional medicine, particularly for acute conditions. Alternative therapies are flourishing alongside conventional medicine. What we are seeing here is a pluralistic and complementary system of health care in which patients choose the kind of practitioner they believe will best be able to help their particular problem. What we do not see is an either/or decision about which kind of practitioner is the one to consult for everything pertaining to health care.

REFERENCES

Andersen, Ronald M. 1995. "Revisiting the Behavioral Model and Access to Medical Care: Does It Matter?" Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36(1): 1-10.

Berger, Earl. 1993. The Canada Health Monitor, Survey No. 9, March, p. 123, Price Waterhouse, Toronto.

Berliner, Howard S. and Salmon J. Warren. 1980. "The Holistic Alternative to Scientific Medicine: History and Analysis". International Journal of Health Services. 10(1):133-47.

Berliner, Howard S. and Salmon J. Warren. 1979. "The Holistic Movement and Scientific Medicine: the Naked and the Dead". Socialist Review 43:31-52.

Coulter, Ian D. 1985. "The Chiropractic Patient: A Social Profile." Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association 29 (1):25-8.

Coulter, Ian D. 1989. "Chiropractic Utilization: A Statistical Analysis." American Journal of Chiropractic Medicine 2(1):13-21.

Eisenberg, David, Ronald Kessler, Cindy Foster, Francis Norlock, David Calkins and Thomas Delbanco. 1993. "Unconventional Medicine in the United States: Prevalence, Costs and Patterns of Use." The New England Journal of Medicine 328:246-252.

Ernst, E. 1995a. "Complementary Medicine: Common Misconceptions." Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 88:244-247.

Ernst, E. 1995b. "Patients' Perception of Complementary Therapies." Forsch Komplementarmed 2:326-329.

Ernst, E, M. Willoughby and Th.Weihmayr. 1995. "Nine Possible Reasons for Choosing Complementary Medicine." Perfusion 8:356-359.

Fulder, Stephen. 1988. The Handbook of Complementary Medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Furnham, Adrian and Smith, Chris. 1988. "Choosing Alternative Medicine: A Comparison of the Beliefs of Patients Visiting a General Practitioner and a Homeopath." Social Science and Medicine 26(7):685-689.

Furnham, Adrian and June Forey. 1994. "A Comparison of Health Beliefs and Behaviours of Clients of Orthodox and Complementary Medicine." British Journal of Clinical Psychology 50:458-46

Furnham, Adrian and Rachael Beard. 1995. "Health, Just World Beliefs and Coping Style Preferences in Patients of Complementary and Orthodox Medicine." Social Science and Medicine 40:1425-1432.

Furnham, Adrian, Charles Vincent and Rachel Wood. 1995. "The Health Beliefs and Behaviours of Three Groups of Complementary Medicine and A General Practice Group of Patients." The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 1:347-359.

Gevitz, Norman (ed.) 1988. Other Healers: Unorthodox Medicine in America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins.

Hayes-Bautista, David. 1977. "Marginal Patients, Marginal Delivery Systems and Health Systems Plans. American Journal of Health Planning. 1(3):36-44.

Kelner, Merrijoy, Oswald Hall and Ian Coulter. 1980. Chiropractors: Do They Help? Markham: Fitzhenry and Whiteside.

Levin, Jeffrey S. and Jennine Coreil. 1986. New Age Healing in the U.S." Social Science and Medicine 23(9):889-97.

McGregor, Katherine J. and Edmund R. Peay. 1996. "The Choice of Alternative Therapy for Health Care: Testing Some Propositions." Social Science and Medicine 43:1317-1327.

Mechanic, David. (Ed). 1982. Symptoms, Illness Behavior, and Help-Seeking. New York: Prodist.

Nathanson C. 1984. "Sex Differences in Mortality." Annual Review of Sociology (10):191-213.

Pescosolido, Bernice and Jennie Kronenfeld. 1995. "Health, Illness, and Healing in an Uncertain Era: Challenges from and for Medical Sociology." Journal of Health and Social Behavior: Extra Issue 5-33.

Roebuck, Julian and Bruce Hunter. 1972. "The Awareness of Health-Care Quackery as Deviant Behaviour." Journal of Health and Social Behaviour 13:162-6.

Saks, Mike. 1992. Professions and the Public Interest. London: Routledge.

Saks, Mike. 1992a. "The Paradox of Incorporation: Acupuncture and the Medical Profession in Modern Britain." Pp. 183-200 in Alternative Medicine in Britain, edited by Mike Saks. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Sharma, Ursula. 1992. Complementary Medicine Today: Practitioners and Patients. London: Routledge.

Thomas, Kate J., Jane Carr, Linda Westlake and Brian T. Williams. 1991. "Use of Non-Orthodox and Conventional Health Care in Great Britain." British Medical Journal 302(26):207-210.

Vincent, Charles and Adrian Furnham. 1996. "Why Do Patients Turn to Complementary Medicine?: An Empirical Study." British Journal of Clinical Psychology 35:37-40.

Wellman, Beverly. 1995. "Lay Referral Networks: Using conventional medicine and alternative therapies for low back pain." Pp. 213-238 in Research in the Sociology of Health Care (1995), Volume 12 Ed. Jennie J. Kronenfeld. Greenwich: JAI Press.

[1] Although people do use alternative therapies for life threatening illnesses such as cancer and AIDS, few such illnesses showed up in this sample. The focus here was on patients, rather than, on specific kinds of illnesses.

[2] Reiki practitioners refer to people who seek their care as clients rather than as patients.

|

|