![]()

-

LAY REFERRAL NETWORKS: USING CONVENTIONAL MEDICINE AND ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES FOR LOW BACK PAIN

Beverly Wellman

ABSTRACT

Seeking solutions to a variety of chronic problems, many North Americans have turned to non-medical practitioners, either as complements to medical care from physicians and hospitals or as alternatives to it. This paper analyzes how persons with low back pain have come to use three different types of practitioners: physicians, chiropractors and Alexander teachers. Analysis systematically compares qualitative, natural history accounts of the three groups of participants with low back pain. The data were gathered through in-depth interviews with thirty-six persons, twelve each receiving care from one of these three types of practitioners. The participants were living in the Toronto area where many alternative types of health care are available, but different types of care receive different amounts of institutional support. All participants have used self-care and received advice from family, friends and co-workers. All had visited a physician soon after they had experienced back pain. However, chiropractic clients have gone on to visit chiropractors and Alexander clients have gone on to visit chiropractors, Alexander practitioners and other types of alternative practitioners. Difference in patterns of use are related to differences in the three clienteles' socioeconomic situations and their social networks. Alexander clients tend to be either artists or social service professionals. Their large, diverse networks are the most likely to provide them with information about a wide range of health care alternatives. Medical clients tend to be working class. Their small, homogeneous networks provide them with little information about health care alternatives. Chiropractic clients, predominantly white collar, have networks that fall in between in size and diversity. They use more alternatives than medical clients but less than Alexander clients.

CHOOSING MEDICAL, LAY OR ALTERNATIVE HEALTH CARE

Processes and Networks

There has been a growing public and scholarly interest in North America in the co-existence of two divergent health care systems: (conventional) medical care and alternative care (e.g., Aakster, 1993, 1986; Konner, 1993; Kronenfeld and Wasner, 1982; McGuire, 1988; Moyers, 1993; Murray and Rubel, 1992). While advances in medical science have raised societal expectations about the possibilities of cure, chronic diseases have proven less amenable than infectious diseases to medical approaches. Seeking solutions to a variety of chronic problems, many North Americans have turned to alternative practitioners: either as complements to medical care or as other approaches to well-being (Wellman, 1991). Concurrently, the recent public interest in health promotion and disease prevention has encouraged a holistic approach, compatible with the rhetoric of many alternative therapies (Barsky, 1988; Gevitz, 1988). This holistic, health promotion emphasis has been particularly salient in Canada, where it has been espoused by the Canadian federal government (Epp, 1986), and several provincial governments as they try to control the costs of publicly-funded health care (Spasoff, et al., 1987; Evans, et al., 1987).

Despite the widespread and growing use of alternative health care in North America, there has been little research into how people with health problems come to use alternative practitioners as substitutes for, or as complements to, conventional practitioners such as doctors and hospitals. This paper examines how thirty-six Torontonians with low back pain have sought help from three types of practitioners: physicians, chiropractors and Alexander teachers. It uses a social network analytic approach to demonstrate the influence of kin and friends on the process of seeking care (McKinlay, 1972; Wellman, 1988). It examines how persons acquire and use information about such alternatives, since they seldom learn about them from their physicians.

Low back pain is a common chronic condition. Estimates are that approximately eighty per cent of Canadians can expect to suffer from low back pain at some point in their adult lifetime (Health and Welfare Canada, 1989). Low back pain sufferers have been shown to seek help frequently from a variety of health care practitioners, most notably, chiropractors (Eisenberg, et al., 1993; Fulder, 1988).

Two types of alternative practitioners, chiropractors and Alexander teachers, were selected for study because of differences in the degree of their professional recognition and the sources of their compensation. Chiropractors are trained in an officially recognized chiropractic college, are licensed in Canada, and have a portion of their services paid for by the universal health insurance plan, as well as coverage by the Workers Compensation Board (Biggs, 1989). By contrast, Alexander teachers have not been trained in a professional school but rather as informal apprentices or in private schools. They are not professionally recognized by the medical establishment, and the cost of their services is not reimbursable by government health plans or private insurance.

Nevertheless, both chiropractors and Alexander teachers treat low back pain disorders by means of physical manipulation, with the aim of reducing neuromuscular tension. Chiropractors claim to reintegrate the body through manipulation of the spine (Kelner, et al., 1980) while Alexander teachers claim to re-habituate muscular functioning by aligning the head, spine and pelvis (Barlow, 1973). Moreover, other differences arise from the office experience and the social and physical context in which health care is delivered. By comparison to Parsons' (1951) analysis that doctors treat their patients, "functionally specific" and "affectively neutral" (Parsons, 1951), both chiropractors and Alexander teachers are reputed to define the situation holistically as interacting with clients or students in order to achieve better functioning.

The Development of Research on Health Care Choices

Three approaches have dominated sociological research into illness behavior and the choices people make about health care (Garro, 1987; Pescosolido, 1992; Telesky, 1987): individual determinants, sociocultural, and social processes.

Individual Determinants of Help Seeking

This approach focuses on how the aggregated characteristics of individuals (sociodemographic factors, beliefs) are related to seeking and using medical care. A number of studies have developed illness-definition and help-seeking models to explain the process through which individuals identify illness, evaluate their situations, and seek medical care (e.g., Becker and Maiman, 1983). They have looked at such topics as: the stages of illness from perception of symptoms to illness resolution, (Mechanic, 1982; Suchman, 1965); access and utilization of the health care system, (Aday and Andersen, 1975); organization of the health care delivery system, (Andersen and Newman, 1973; Kohn and White, 1976); the physician-patient relationship, (Freidson, 1961; Marshall, 1981); changes in physician authority, (Haug and Lavin, 1983); and the effects of technology on health care, (Marshall, 1987). Such studies have concentrated on how predisposing, enabling and illness factors affect health care behavior (e.g., Frank and Kamlet, 1989; Portes, et al., 1992). Predisposing factors are characteristics which exist prior to illness and which may affect behavior. They include demographic factors (e.g., age), social positions (e.g., ethnicity) and beliefs (e.g., values, attitudes and knowledge). Enabling factors refer to household (e.g., income) and community (e.g., cost, transportation) factors that can facilitate or inhibit use. Illness factors may affect health care utilization depending on the individual's subjective and objective evaluations of the illness episode.

However varied their models, all individual determinants aggregate the characteristics of individuals without directly studying the social networks in which they are embedded or the sociocultural systems within which they operate. In effect, these are rational-choice models, linking socio-demographic characteristics with attitudes to the seeking of health care (Pescosolido, 1992). Their implicit analytic model is survey-research in which the responses of many individuals are correlated and cross-classified structurally in order to infer social patterns (Wellman, 1988). Their implicit cultural frame of reference is mainstream American society.

Socio-Cultural Determinants of Help-Seeking

The socio-cultural approach emphasizes the influence of culture and reference groups on early states of symptom recognition and evaluation. Such researchers have focused on how norms and values affect perceptions of illness and seeking help (Angel and Thoits, 1987; Chrisman and Kleinman, 1983; Zola, 1966). Socio-cultural analysts, often working in the ethnographic tradition, have analyzed how illness-labelling and help-seeking affects the identification of and responses to illness (Lipton and Marbach, 1984; Suchman, 1965) For example, Zborowski (1952) attributed differences in response to pain between four American ethnic groups to their different cultural patterns of emotion, stoicism and denial. He argued that these cultural differences were associated with variations in the ways in which ethnic groups attended to and interpreted bodily states.

Anthropologists have been using different theorectical and methodological approaches to describe in great detail how folk healers and western medicine relate, co-exist and compete in treating a whole range of complaints (e.g., Fuchs and Bashur, 1975; Riley, 1980; Romannucci-Ross, 1977; Wolffers, 1988). They have examined the conditions under which people think about their bodies, evaluate symptoms, and seek advice and help from a wide range of health care practitioners (Janzen, 1978; Young, 1981; Kleinman, 1980; Lock, 1980). Such work nicely shows the power of analyzing both official (medical) and alternative health care within the same analytic model.

Social Processes Affect Help-Seeking

To study the effects of culture and reference groups with regard to illness behaviour and the cirucumstances under which people seek help, social network analysis has become an important analytic tool for studying the impact of family, friends and lay others on the process of seeking medical care (McKinlay, 1972; Salloway and Dillon, 1973; Pescosolido, 1986; Pilisuk and Park, 1986). People do not function in society solely as individuals, but also as members of interpersonal, organizational and interorganizational networks. Their networks are their social capital (Coleman, 1988; Wellman and Wortley, 1990), providing them with resources to cope with routine and extraordinary circumstances and with links to others who may be of use. Weak ties may be important venues for the diffusion of information because they are more apt to be between socially-dissimilar persons and to reach different social circles. Hence they can transmit a greater range of information, such as a wider variety of potential health care practitioners (Granovetter, 1973, 1982; Feld, 1982; Burt, 1992).

By focusing on pathway studies, a type of network process study, one can specify linkages between different physicians as people negotiate their way to care (e.g., Strain, 1988). Instead of addressing the question who uses health services, the emphasis is on why and how an individual seeks medical care (Sharma, 1992; Zola, 1973). Sociologists have been examining how the nature of social networks affects the use of health services through networks' impact on reference groups, access to opportunities, social pressures, and information flows. For example, persons whose social networks are composed primarily of kin tend to be low utilizers of health care while those whose social networks are composed primarily of friends tend to be heavy utilizers (McKinlay, 1975). Lay people are often consulted for advice on how to deal with symptoms (Freidson, 1961). Thus when abortion was illegal, many women used ties with close friends and kin to find practitioners (Lee, 1969; Badgley, et al., 1977). Indeed, Kleinman (1980) argues that the "popular sphere" of health care is the largest part of any system and the most poorly understood; he estimates that 70-90% of all illness episodes in the United States and Taiwan are initially managed within the lay sector. Contact is made with professionals only as a last resort.

The process approach has usefully integrated analyses of lay and medical help-seeking in North America, and it has integrated analyses of traditional and medical (alternative) help-seeking in the Third World. There has not yet been, however, any study of North American health care which integrates the various patterns of help-seeking from alternative practitioners, medical practitioners and lay-people.1

METHODS

The data come from a client-based retrospective design, studying people with low-back pain who at the time of the interviews (1988-1989) were seeing three selected types of health care practitioners in metropolitan Toronto. The sampling strategy involved a multistage process of identification, selection and contact of: (a) three physicians, three chiropractors and three Alexander teachers; (b) samples of four persons attending each of these health care practitioners. The sample size is thirty-six (3x3x4).

In choosing the nine health care practitioners, I used a convenience sample of practitioners. I tried to ensure a diversity of ages, education and years in practice in order to minimize idiosyncratic bias that might attract clients to certain practitioners. After an introductory meeting, each practitioner agreed to provide a sample of their clients with low back pain after they had talked with them about the study and obtained their consent. Each practitioner obtained a representative sample of four clients on a particular day (and if that was not possible then for a longer period). Although this sampling procedure did not allow me to discover what proportion of people with low back pain go to physicians, chiropractors or Alexander teachers, it did enable me to investigate how the people who were seeing these practitioners got there.2

Each open-ended interview with the 36 clients lasted approximately one and three-quarter hours. The length of the interview reflected the amount and depth of information needed to build a comprehensive portrait in order to examine the reasons and the ways in which people find health care practitioners. A multidimensional approach (including both individual and social factors) was taken, with a focus on six key types of variables:

• need in terms of an individual's objective and perceived severity of low back pain;

• experiences with initial medical care;

• network relations providing clients with information, guidance, access and support with respect to physicians, chiropractors and Alexander teachers;

• attitudes about health and the extent of their faith in medical treatment;

• socio-demographic characteristics;

• accounts of when they noticed that something was wrong, who was the first person with whom they talked, and what was the first thing they did.

All of the participants were forthcoming in the stories that they had to tell about their backs and how it had affected their lives. Information flowed easily, although participants sometimes had to backtrack in order to remember the sequence of events. In some cases, people referred to their diaries to help sort out dates, frequency and order of visits, and financial matters. To minimize the selective recall of events and information, I examined in detail only the most recent incident of back pain that brought these clients to treatment. I also used a variety of probes throughout the interview in order to compare responses systematically.

The data suggest that socioeconomic characteristics are associated with the heterogeneity of networks, and that in turn, the characteristics of such networks -- "who you know" -- influences the health care strategies exhibited by the three groups. In the next sections, I compare the individual determinants (i.e., age, occupation, education, health status) of the three clienteles, their networks of information and referral, and their different patterns of help-seeking.

INDIVIDUAL DETERMINANTS OF CLIENTS

Social Characteristics

Medical Clients

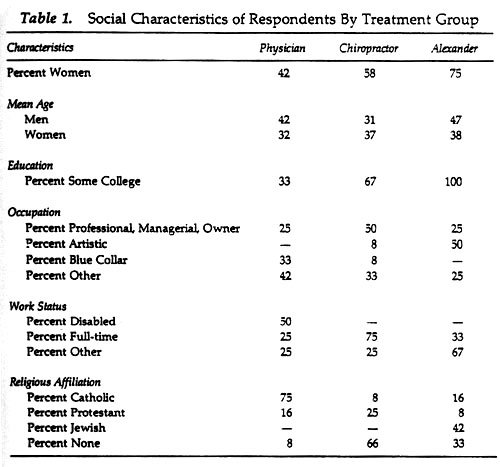

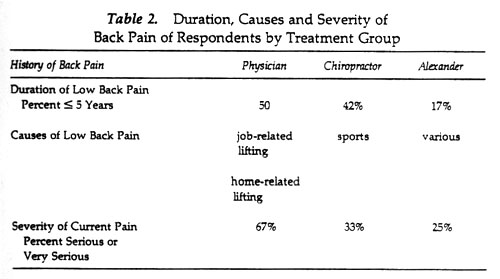

These are men and women generally in their thirties and forties,3 and in blue collar or low managerial occupational positions. Most are either disabled at present or have previously been disabled (Table 1). They usually hold jobs that make referrals to the Workers' Compensation Board (WCB) for dealing with occupational injuries, and they generally have incurred their back injuries through repetitive lifting: e.g., roofer, distributor of packaging materials and shipping foreman (Table 2). Half reported that they had their back problems for at least one year but not more than five years. Indeed half of them are presently WCB cases, and are collecting disability pay from the WCB. In such cases, the WCB determines the length and type of treatment to be given before the workers are taken off disability pay and ordered back to work. The WCB refers its workers to treatment by physicians and hospitals, and it never refers to chiropractors or Alexander teachers. The medical clients tend to be less educated (33% have attended some college) than either the chiropractic (67%) or Alexander clients (100%). Slightly more than half are men (58%) and three-quarters are Catholic (Table 1).

Chiropractic Clients

By comparison, chiropractic clients are well-educated men and women in their thirties, in professional and upper managerial jobs such as litigation lawyer, editor and carpenter (Table 1).4 Their back problems stem more from their active involvement with sports than from work related injuries (Table 2). They have had low back problems for a substantial number of years, 42% of chiropractic clients have had low back pain for at least five years. Although one-third thought their back pain to be serious, it did not hinder anyone's ability to work full-time (Tables 1 and 2). Like the medical clients, there are about equal numbers of men and women in the chiropractors' clientele (in accord with Coulter's larger study of 1985). By contrast to the predominantly Catholic medical clientele, more than half (66%) of the chiropractic clientele report no religious affiliation (Table 1).

Alexander Clients

The Alexander clientele are mostly women (75%), well educated, and working free-lance in social services and the arts (Table 1). They attribute their back pain mainly to sports and motor vehicle accidents, and 83% report having lived with back problems for most of their lives (Table 2). Unlike the medical clients, none have been incapacitated by their backs or have had to stop working (Table 1). Their jobs give them flexible schedules to attend to their backs, and their work is less likely to involve heavy lifting.5 By further comparison to the physician and chiropractic groups, this is a more heterogeneous group ethnically (e.g., Jewish, American, French Canadian, Irish and Chinese Jamaican). Very few said they engaged in religious activities on a regular basis.

Health Characteristics, Behavior, Attitudes and Knowledge

People's perception of their general state of health may influence the attention they pay to their back pains (regardless of severity) and the treatment they seek. In addition, their faith and respect for different kinds of treatment may directly affect their choices (Hill, 1981).

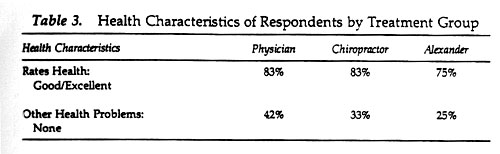

Health Characteristics

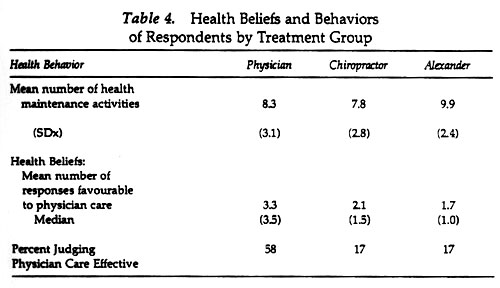

All three clienteles report that they consider themselves to be generally healthy (Table 3). The big difference is in back pain: Two-thirds of the medical clients rate their back pain as serious, compared to one-third for the chiropractic clientele and one-quarter for the Alexander clientele (Table 2). Yet the Alexander clientele mention more health problems (e.g., high cholesterol, irritable bowel syndrome and migraine headaches) and pay somewhat more attention to health prevention and health maintenance practices, frequently discussing bodily aches and pains (Table 4). They consider this to be a normal, routine part of their lives. Alexander clients are often involved with artistic occupations that make the body a salient issue, such as being a dancer, musician or actor.

Health Behavior

Participants reported engaging in nearly half of the 20 health practices I asked them about, such as regular exercise or a special diet. Consistent with their greater interest in the body, Alexander clients engage in slightly more practices (9.9) than medical (8.3) and chiropractic (7.8) clients (Table 4).

Health Attitudes

I asked a series of questions from the World Health Organization's scale of medical beliefs and tendencies to use medical services. The degree to which the three clienteles were skeptical of medical care with regard to their back problems was related directly to the practitioner they were attending at the time of interview. The clients of physicians were the least skeptical of all three clienteles; those seeing a chiropractor were more skeptical of medical care, while those attending Alexander teachers were the most skeptical (Table 4).

Similar attitudes appeared when the participants were asked: "In general, do you think physicians provide effective treatment?" More than half (58%) of the medical clients answered positively, although few elaborated on their answers (Table 4). By contrast, less than one-fifth of the chiropractic and Alexander clientele said that their physicians provided effective treatment. About half of the chiropractic and Alexander clientele gave ambivalent yes/no answers.

In almost all cases, participants agreed that their back care from physicians was not adequate and blamed it on the large, bureaucratic health care system. They made particular mention of insufficient time spent with clients and inappropriateness of physician treatments to back care (i.e., drugs and prolonged bed rest). They perceived this latter problem as a result of poor medical training and experience with chronic illness. As one chiropractic client said, "Phyusicians do what they can but they don't have the time."

Health Knowledge

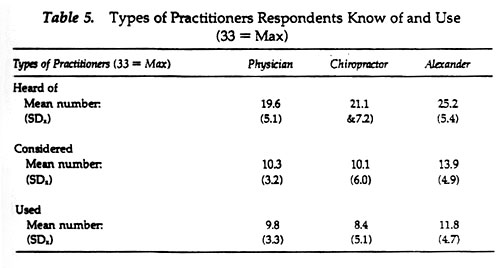

Since "choice" is one aspect of "use" and both are dependent on availablility, awareness, knowledge, and financial capability, it was important to learn if the participants had heard of, considered or used many of the treatment options available in Toronto. Out of a list of 33 types of practitioners that were presented in the questionnaire (Figure 1), the clients of physicians had heard of 19.6, the clients of chiropractors had heard of 21.1 and the clients of Alexander teachers had heard of 23.9 (Table 5). All three clienteles had considered using half of those they had heard of and had used most of those they considered. This data complements Berger's Canadian survey (1990), about one fifth of Canadians have used an alternative practitioner.

Although medical clients had firm beliefs and respect for their physicians, they also said they were less familiar with other treatment options. By contrast, Alexander clients were the most skeptical of physicians, they most involved with their body, and discussed their health with their friends and relatives the most.

SOCIAL NETWORKS AND SOCIAL PROCESSES

Social Networks

Information from Network Members

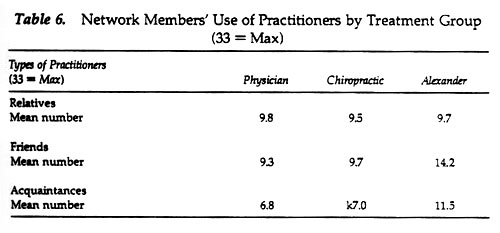

To evaluate the impact of social network relations on the use of different types of practitioners, I gave the participants the same list of 33 types of practitioners and asked them if they knew whether any of their relatives, friends or acquaintances had used any of them. The mean number of types of practitioners that the participants report their relatives have used is similar for all three groups, slightly less than ten (Table 6). However, friends of the Alexander clientele have used more types of practitioners (mean = 14.2) than friends of chiropractic clientele (9.7) and, especially, friends of the medical clientele (9.3). Similarly, acquaintances of the Alexander clientele have used a broader range of practitioners (11.5) than those of the chiropractic and medical clienteles (6.8).

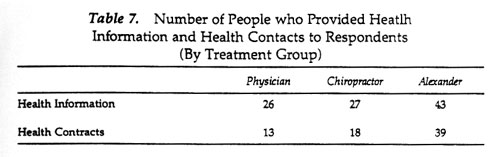

The Alexander clients name a more diverse set of friends and acquaintances than medical or chiropractic clients from whom they obtain information about treatment alternatives. They know considerably more people who have used a variety of treatments and who are passing that information on to network members (Table 7). In addition, they also report having more discussions with network members about health and health-care, and they appear to have obtained more specific information about back care from them.

Strong and Weak Ties

Do people with stronger or weaker relationships in their networks get more information about health-care? Although strong, intimate ties generally provide more social support (Wellman, 1992), Granovetter has argued (1973, 1982) that persons with more weak ties (which usually means more heterogeneous networks) are likely to acquire a wider range of information. This suggests that clients with more weak ties should know about more health care alternatives.

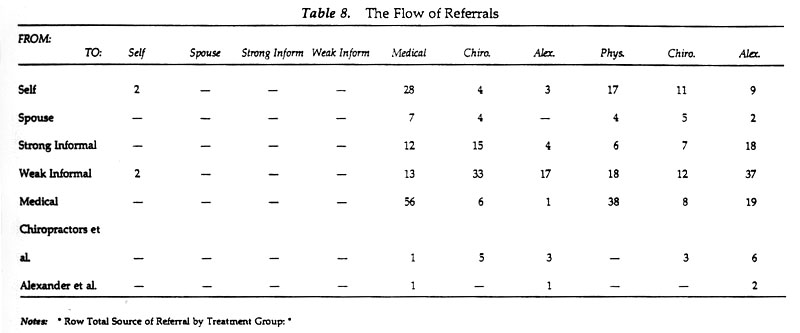

Referral data constructed from health-care pathways and information about network relations shows what kinds of ties have led to the use of different types of health care.7 Medical clients rarely name weak informal relations as sources of information about health care (Table 8). Rather, they go directly to physicians who are already known by them, their employer or their family doctors for referrals. By contrast, chiropractic clients learn about chiropractors mainly through their weak informal relations, and to a lesser extent from spouses and close friends and relatives. Alexander clients are even more apt to have learned about their caregivers from weak informal relations such as friends of kin, friends of friends, and weak ties with dancers and actors. Moreover, many of the Alexander clients who have also used chiropractors report that they learned about their chiropractors through weak and strong network ties.

Patterns of Using Practitioners

Initial Contacts

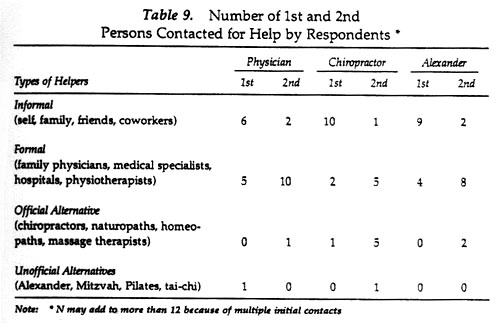

Based on the accounts of participants, it appears that back care begins before any decision is made to seek help. Many participants have lived with pain for long periods of time before supplementing self-care with professional care. They have rarely walked into a practitioner's office without first obtaining advice from friends, relatives or co-workers. Half (50%) of the medical clients initially discussed their back pain with members of their family, people at work and a friend, in that order (Table 9). One-third (33%) reported consulting with their family doctor about their back pain, and one (8%) went directly to the hospital for help. Only one person (8%) sought advice from an outside source, an instructor at her fitness center.

Medical clients usually sought medical care quickly regardless of their initial discussions with lay people. In general, those who first went to their family doctor subsequently went to a specialist, physiotherapist or used self-care (Table 9). Those who first consulted with network members then went to their family doctor. In only one instance did a consultation with a family member lead directly to an alternative practitioner such as a chiropractor.

By comparison, chiropractic clients usually go to chiropractors on the recommendation of network members or other alternative practitioners whom they already are using to deal with other kinds of health problems (Table 9). Ten of the chiropractic clients (83%) spoke first to their family, friends and co-workers, two people (17%) went straight to their family doctor (in one case the family doctor was also a friend), and one went (8%) to her homeopathic physician.8 Of the ten who spoke initially with social network members, four next went to a physician, five went directly to a recommended chiropractor and one went to a massage therapist. Of the two who visited their family doctor first, one was advised to try physiotherapy and the other massage. The one woman who regards her homeopath as her regular physician followed his recommendation to see a chiropractor.

Alexander clients made contact with alternative practitioners only after much trial and error (Table 9). They initially used self-care and got advice from family, friends, co-workers, (75%) and formally from family doctors, specialists and physiotherapists (33%). Only 17% had contacted an alternative practitioner as early as their second contact.

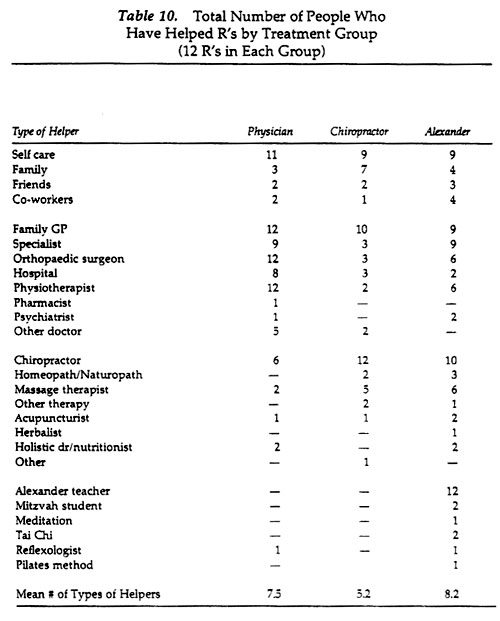

Practitioners Consulted

Medical clients have used the least diversified set of practitioners. Although they have had contact with several practitioners, almost all are physicians (family doctors, specialists, surgeons) and medically-approved ancillaries such as physiotherapists (Table 10). Indeed, medical sources have provided primary care for all twelve of these clients, and all have been involved with a family doctor, special physician(s) and physiotherapist(s). Moreover, eight have been to the hospital for surgery or for opinions about the usefulness of surgery.9 Half of the medical clients sought the assistance of a chiropractor at later stages in their health-seeking pathways and less than a handful of people used alternatives such as massage and acupuncture. At the time of interview, the mean number of health care practitioneers used was 11.3 and the mean number of types of helpers was 7.5 (Table 10). The difference reveals multiple practitioners within each type, used either consecutively or simultaneously. It is also noteworthy to mention that informal encounters and self-care play major roles in all twelve pathways under consideration.

Chiropractic clients have used fewer health care practitioners than Alexander clients and medical clients (Table 10). Yet it is important to emphasize that all twelve of these clients have not rejected the use of physicians for their back care. Ten have used family doctors, five mention contact with medical specialists, and two have gone to physiotherapists. In addition to chiropractors and physicians, chiropractic clients have also used massage therapists (41%), homeopaths (17%), acupuncture (8%) and a fitness club (8%). No one mentioned having used other, more obscure, forms of alternatives such as rolfing. On average, the chiropractic clients in this study consulted with 5.9 health care practitioners and have been helped by 5.2 types of practitioners (Table 10).

Self-care shows up significantly in the pathways of 9 chiropractic clients (75%), and it appears at all points in their pathways. In addition to routine office visits, chiropractic clients are often encouraged to follow an exercise regimen at home.

Alexander clients, like physician clients and unlike chiropractic clients, use many health care practitioners. On average, the total number of health care practitioners used was 11.8 and the number of types of helpers was 8.2 (Table 10). In the words of one participant, Alexander clients use "lots of everything": Alexander teachers, Mitzvah teachers (a Toronto variation on Alexander), and their students, massage therapists, the martial arts, chiropractors, naturopaths, homeopaths, psychotherapists, family physicians, specialists, surgeons, and their family, friends and co-workers. As one Alexander client said: "Once you're in an alternative circle, the support and recommendations seem to multiply."

Alexander practitioners are a last resort, appearing far along health care pathways. It is important to remember that initial contacts were similar for all three clienteles and that Alexander clients have also used one or more physicians and chiropractors. In fact, 83% cent of those people who are using Alexander practitioners have used chiropractors, doctors (including specialists and physiotherapists) and other forms of alternative health care such as Tai-chi and Pilates (Table 10).

Self-care has also played a major role in their pathways at all stages of health care. Nine people have used self-care in their pathway, and four of them have used it twice. Self-care not only determines when the decision is made to seek help from a health care practitioner (either in the formal or informal sector) or at different stages of the pathway, but it also reflects the response to comply or not with a recommended treatment regimen.

Social Processes

Pathways

The strategy of all clients in this study included self-care as well as lay consultation with family, friends and co-workers. They typically tried this before using any kind of health care practitioner. Pathways to care were not necessarily linear progressions from self-care through informal to formal care. There were many multiple pathways -- two or more sources of care being used at once -- and many interludes in which clients used only self-care. What is clear is that the three clienteles exhibited different patterns and combinations of health care use.

Medical clients are "single users." They almost always obtain care from physicians, or from therapists recommended by -- and influenced by -- physicians, such as physiotherapists and massage therapists. A few have tried chiropractors, but none have tried the less institutionally recognized alternatives. Yet medical clients have consulted with a large number of doctors: they have consulted with as many physicians (an average of twelve) as Alexander clients have consulted with all types of practitioners. Figure 2 presents a typical case. A woman who is presently a housewife with a small child began having back pain five years ago. She was a data entry clerk, sitting long hours at the keyboard. At first, she was forced to go on short term disability which later resulted in long term disability. More recently, a car accident in 1989 brought this woman back to the physician for help. There are seven steps to her physician-patient pathway, beginning at the family doctor and ending with self-care. The family doctor recommended x-rays, physiotherapy and further consultation with an orthopaedic surgeon. This initiated a linked set of medical referrals from one orthopaedic surgeon to another. Although she has not received satisfaction for her back pain from her doctors, neither has she give up on medical care. At the time of the interview, however, she had resorted to self-care only. When I asked her about chiropractors, she only had a vague notion about what they did. This is the conversation I had with her:

Int: So no one has suggestsed that you go to a chiropractor or anything like that?

Resp: No, I have never been to a chiropractor. They are the people that crack your bones and everything right. No, I've never been to one.

Int: So, basically you have been to physicians, orthopaedic surgeons and to physiotherapists. And you haven't gone back to the physiotherapist because it has not done anything for you.

Resp: I do my own. I do exercises and I put the heating pad on. I try to avoid things that aggravate it, which is hard.

Two things were true for this woman; she did not have the networks and she had confidence in her own judgment and that of her family physician. In addition, she did not know anyone else with a similar back condition and had no one with which to share health information or health contacts.

Chiropractic clients are "dual users." In addition to medical care, they have used the more institutionally recognized non-medical forms of care such as chiropractors, homeopaths and naturopaths. However, none had gone to less recognized practitioners such as Alexander teachers, rolfers or reflexologists. During their last episode of back pain, chiropractic clients have consulted with fewer health care practitioners than the other clients.

Figure 3 is typical of chiropractic clients. A 41 year-old lawyer has sought help from three chiropractors and a family doctor (not his original physician). His initial use of chiropractors was closely linked to the advice of his wife, who works for one, firmly believes in them, and supports and encourages his use of them. But the deciding factor to influence his decision to try his wife's chiropractor, came after his family doctor recommended surgery. Over time, however, he phased out the use of his wife's chiropractor because he felt the adjustments were not helping much and he was able to "live with" his condition. Nonetheless at a later time, when a close friend who was a manufacturer of orthotics suggested he try his chiropractor, the participant said: "I was in a frame of mind to act upon his referral."

This lawyer's response to his family physician is not uncommon. Several chiropractic clients explicitly stated that the medical experience, drug therapy, prolonged bed-rest, and the professional physician-patient relationship made alternatives more attractive. For example the following person expresses the sentiments of chiropractic clients in general with respect to back care:

I don't think physicians provide effective treatment. I don't think they are equipped to treat people. They are disease oriented, not symptom oriented. They're good technicians but not good at dealing with chronic illness. They can't deal with mental symptoms except band-aid solutions with drugs.

Almost all of those who sought help from chiropractors made their choice of modality on the recommendation of either network members (close family members, friends, co-workers) or other alternative practitioners (such as homeopaths and naturopaths) whom they regularly use as sources of health care. The chiropractic clients' pathways to care are comparatively direct and shorter in length than those of the medical or Alexander clients. Their pathways often reflect consecutive use of several chiropractors as they accept the approach but seek to get more relief from different chiropractic practitioners, in ways similar to the physician client pathways.

Alexander clients are "multiple users." In addition to visiting Alexander teachers to deal with their low back pain, they have used other types of alternative practitioners as well as chiropractors and physicians. Indeed, some are currently using other forms of health care in addition to the Alexander technique. On the average they have consulted with twelve health care practitioners of varying types beginning with the most recent episode of back pain. By contrast to the direct, short pathways of chiropractic clients and the long, medically focused pathways of medical clients, the pathways of Alexander clients are long and complicated. They show simultaneous and consecutive use among and between many types of practitioners.

For example, Figure 4 shows a 37 year-old psychiatric nurse working in a major Toronto hospital. Her back problem began, fairly typically, while helping a friend move. She has an extensive network that supplies her with information and guidance to all levels of health care. The intersection of family, friends, co-workers and psychiatrist has provided her with a good deal of health care advice.

CONCLUSIONS

The medical, chiropractic and Alexander clienteles differ in their socioeconomic statuses, health practices and beliefs, social networks, and pathways to treatment. To some extent, the occupational and health practices/beliefs differences between the three clienteles supports an individual determinants model. But are these really individual determinants? Reference group theory has shown that sociocultural differences transmitted through interpersonal relations affect beliefs and practices (Erickson, 1988). And occupational differences are associated with another interpersonal phenomenon: People in some occupations have larger and more complex social networks, and these are the people who tend to become clients of chiropractors and Alexander teachers. Moreover, the higher educational level of these two clienteles means that they -- and the members of their networks -- are more apt to have acquired a wider range of information, including information about alternatives to medical care. Their jobs also give them more opportunities to meet other people who are inclined to think about the body and alternatives to medical care.

The evidence shows that different types of networks provide different amounts of health information and health contacts, leading subsequently to the different use patterns displayed by the three clienteles. The networks of Alexander clients are the most heterogeneous with respect to socioeconomic status and residential dispersion. The networks of chiropractic clients are less heterogeneous, while the networks of medical clients are the least heterogeneous. These findings are consistent with Granovetter's conjecture (1973) and Lee's demonstration (1969) that the more heterogeneous the network the more possible it is for network members to provide access to a wide range of resources. The Alexander clients are in the most heterogeneous networks and have been in contact with the widest range of practitioners. The medical clients have the least heterogeneous networks, and although they have seen as many practitioners as the Alexander clients, they have tended to use only physicians.

In general, although all three groups were frustrated and disappointed with medical care, those who used alternative health care were neither dedicated believers in it nor eager consumers shopping around for the best care. All of the Alexander clients and the chiropractic clients had been medical clients; some still were. Yet whatever practitioners they have seen, few clients have searched systematically for health care practitioners. Rather, it seems that as people go about their lives, they receive information from a variety of sources. Information about chiropractors and Alexander teachers flowed to participants more frequently than information gained from deliberate searching for a chiropractor or an Alexander teacher. In this study, more information and contacts flowed to those who had more resources, both personally (higher socioeconomic status) and through their networks.

One implication from the data is that different types of people use an array of practitioners for a variety of reasons; alternating between lay, medical and alternative care. The health care choices that the participants made were not mutually exclusive "either/or" decisions to seek help from physicians or from alternative practitioners. Rather, they have sought help from a variety of sources that appeared to them to offer reasonable hope of relief.

REFERENCES

Aakster, C.W. 1986. "Concepts in Alternative Medicine." Social Science and Medicine, 22 (2):265-73.

Aakster, C.W. 1993. "Concepts in Alternative Medicine." Pp. 84-93 in Health and Wellbeing: A Reader, edited by A. Beattie, M. Gott, L. Jones and M. Sidell. London: MacMillan.

Aday, Lu Ann and Ronald Andersen. 1975. Development of Indices of Access to Medical Care. Ann Arbor, MI: Health Administration Press.

Andersen, Ronald and John F. Newman. 1973. "Societal and Individual Determinants of Medical Care Utilization in the United States." Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 51 (1):95-124.

Angel, Ronald and Peggy Thoits. 1987. "The Impact of Culture on the Cognitive Structure of Illness." Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 11 (4):465-494.

Badgley, Robin F., Denyse Fortin-Caron and Marion G. Powell. 1987. "Patient Pathways: Abortion." Pp. 159-171 in Health and Canadian Society, edited by David Coburn, Carl D'Arcy, George Torrance and Peter New. Toronto: Fitzhenry and Whiteside.

Barlow, Wilfred. 1973. The Alexander Principle. London: Gollancz.

Barsky, A.J. 1988. Worried Sick: Our Troubled Quest for Wellness. Boston: Little Brown.

Becker, Marshall and Lois Maiman. 1983. "Models of Health-Related Behaviour." Pp. 539-68 in Handbook of Health, Health Care, and the Health Professions, edited by David Mechanic. New York: Free Press.

Berger, Earl. 1990. The Canada Health Monitor, Survey #4 Toronto: Price Waterhouse.

Biggs, Catherine L. 1989. "The Professionalization of Chiropractic." Doctoral dissertation, Department of Community Health, University of Toronto.

Burt, Ronald. 1992. Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Chrisman, Noel and Arthur Kleinman. 1983. "Popular Health Care, Social Networks, and Cultural Meanings: The Orientation of Medical Anthropology." Pp. 569-590 in Handbook of Health, Health Care and the Health Professions, edited by David Mechanic. New York: Free Press.

Coleman, James. 1988. "Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital." American Journal of Sociology 94:s95-s120.

Coulter, Ian D. 1985. "The Chiropractic Patient: A Social Profile." Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association 29 (1):25-8.

Eisenberg, David, Ronald Kessler, Cindy Foster, Francis Norlock, David Calkins and Thomas Delbanco. 1993. "Unconventional Medicine in the United States: Prevalence, Costs and Patterns of Use." The New England Journal of Medicine 328:246-252.

Epp, Jake. 1986. "Achieving Health for All: A Framework for Health Promotion." Ottawa: Ministry of National Health and Welfare.

Erickson, Bonnie. 1988. "The Relational Basis of Attitudes." Pp. 99-122 in Social Structures: A Network Approach, edited by Barry Wellman and S.D. Berkowitz. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Evans, John, Mathilde Bazinet, Alexander Macpherson, Murray McAdam, Sister Winnifred McLoughlin, Dorothy Pringle, Rose Rubino, Hugh Scully, Greg Stoddart and W. Vickery Stoughton. 1987. "Toward A Shared Direction for Health in Ontario." Toronto: Ontario Health Review Panel.

Feld, Scott. 1982. "Social Structural Determinants of Similarity among Associates." American Sociological Review 47 (December):797-801.

Frank, Richard G. and Mark S. Kamlet. 1989. "Determining Provider Choice for the Treatment of Mental Disorder: The Role of Health and Mental Health Status." Health Services Research 24:83-103.

Freidson, Eliot. 1961. Patients' Views of Medical Practice. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Fuchs, Michael and Rashid Bashur. 1975. "Use of Traditional Indian Medicine Among Urban Native Americans." Medical Care 13:915-27.

Fulder, Steven. 1988. The Handbook of Complementary Medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Garro, Linda. 1987. "Decision-Making Models of Treatment Choice." Pp. 173-188 in Illness Behaviour, edited by Sean McHugh and Michael Vallis. Plenum Publishing Corporation.

Gevitz, Norman (ed.) 1988. Other Healers: Unorthodox Medicine in America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins.

Gottlieb, Benjamin and Peter Selby. 1990. "Social Support and Mental Health: A Review of the Literature." Working Paper, Department of Psychology, University of Guelph, Canada.

Granovetter, Mark. 1973. "The Strength of Weak Ties." American Journal of Sociology 78:1360-80.

Granovetter, Mark. 1982. "The Strength of Weak Ties: A Network Theory Revisited." Pp. 105-30 in Social Structure and Network Analysis, edited by. Peter Marsden and Nan Lin. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Hamilton, Barbara Jean. 1986. "The Alexander Technique: A Practical Application to Upper String Playing." Master's thesis, Department of Music, Yale University.

Haug, Marie and Bebe Lavin. 1983. Consumerism in Medicine: Challenging Physician Authority. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Health and Welfare Canada, Health Services and Promotion Branch. 1989. Knowledge Development for Health Promotion: A Call for Action. Ottawa: Supply and Services Canada.

Hill, Richard. 1981. "Attitudes and Behaviour." Pp. 347-77 in Social Psychology: Sociological Perspectives, edited by Morris Rosenberg and Ralph Turner. New York: Basic Books.

Janzen, J. 1978. The Quest for Therapy in Lower Zaire. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kelner, Merrijoy, Oswald Hall and Ian Coulter. 1980. Chiropractors: Do They Help? Markham: Fitzhenry and Whiteside.

Kleinman, Arthur. 1980. Patients and Healers in the Context of Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kohn, Robert and Kerr L. White. 1976. Health Care: An International Study. London: Oxford University Press.

Konner, Melvin. 1993. Medicine at the Crossroads: The Crisis in Health Care. New York:Pantheon.

Kronenfeld, Jennie J. and Cody Wasner. 1982. "The Use of Unorthodox Therapies and Marginal Practitioners." Social Science and Medicine, 16:1119-25.

Lee, Nancy [Howell]. 1969. The Search for an Abortionist. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Lipton, James A. and Joseph Marbach. 1984. "Ethnicity and the Pain Experience." Social Science and Medicine 19 (12):1279-98.

Lock, Margaret M. 1980. East Asian Medicine in Urban Japan. Berkeley: University of California.

Marshall, Joanne Gard. 1987. "The Adoption and Implementation of Online Information Technology by Health Professionals." Doctoral dissertation, Department of Community Health, University of Toronto.

Marshall, Victor. 1981. "Physician Characteristics and Relationships with Older Patients." Pp. 94-118 in Elderly Patients and Their Doctors edited by Marie Haug. New York: Springer.

McGuire, M. 1988. Ritual Healing in Suburban America. New Brunswick, N.J.:Rutgers.

McKinlay, John. 1972. "Some Approaches and Problems in the Study of the Uses of Services." Journal of Health and Social Behaviour 13 (6):115-152.

McKinlay, John. 1975. "The Help-Seeking Behaviour of the Poor." In Poverty and Health, edited by John Kosa and Irving Zola. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Mechanic, David (ed.) 1982. Symptoms, Illness Behavior, and Help-Seeking. New York: Prodist.

Moyers, Bill. 1993. Healing and The Mind. New York: Doubleday.

Murray, Raymond and Arthur Rubel. 1992. "Physicians and Healers -- Unwitting Partners in Health Care." New England Journal of Medicine 326:61-64.

Parsons, Talcott. 1951. The Social System. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

Pescosolido, Bernice. 1982. "Medicine, Markets and Choice: The Social Organization of Decision-Making and Medical Care." Doctoral dissertation, Department of Sociology, Yale University.

Pescosolido, Bernice. 1986. "Migration, Medical Care Preferences and the Lay Referral System: A Network Theory of Role Assimilation." American Sociological Review 51 (August):523-540.

Pescosolido, Bernice. 1992. "Beyond Rational Choice: The Social Dynamics of How People Seek Help." American Journal of Sociology 97 (4):1096-1138.

Pilisuk, Marc and Susan Hillier Parks. 1986. The Healing Web. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England.

Portes, Alejandro, David Kyle and William Eaton. 1992. "Mental Illness and Help-seeking Behaviour Among Married Cuban and Haitian Refugees in South Florida." Journal of Health and Social Behavior 33:283-298.

Riley, James N. 1980. "Client Choices Among Osteopaths and Ordinary Physicians in a Michigan Community." Social Science and Medicine 14B:111-20.

Romanucci-Ross, Lola. 1977. "The Hierarchy of Resort in Curative Practices: The Admiralty Islands, Melanesia." Pp. 481-86 in Culture, Disease and Healing, edited by David Landy. New York: Macmillan.

Salloway, Jeffrey and Patrick Dillon. 1973. "A Comparison of Family Networks and Friend Networks in Health Care Utilization." Journal of Comparative Family Studies 4 (1):131-42.

Sharma, Ursula. 1992. Complementary Medicine Today: Practitioner and Patients. London: Tavistock/Routledge.

Spasoff, R., P. Cole, F. Dale, D. Korn, P. Manga, V. Marshall, F. Picherack, N. Shosenberg and L. Zon. 1987. "Health for All Ontario." Report of the Panel on Health Goals for Ontario.

Strain, Laurel Ann. 1988. "Physician Utilization and Illness Behaviour in Old Age: Prediction and Process." Doctoral dissertation, Department of Community Health, University of Toronto.

Suchman, Edward. 1965. "Stages of Illness and Medical Care." Journal of Health and Human Behaviour 6:114-128.

Telesky, Carol W. 1987. "The Effects of Chronic Versus Acute Health Problems, Social, and Psychological Factors on Reports of Illness, Disability, and Doctor Visits for Symptoms." Doctoral dissertation, Department of Sociology, University of California, Los Angeles.

Verbrugge, Lois. 1986. "From Sneezes to Adieux: Stages of Health for American Men and Women." Social Science and Medicine 22 (11):1195-1212.

Wellman, Barry. 1988. "Structural Analysis: From Method and Metaphor to Theory and Substance." Pp. 19-61 in Social Structures: A Network Approach, edited by Barry Wellman and S.D. Berkowitz. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wellman, Barry. 1992. "Which Types of Ties and Networks Give What Kinds of Social Support?" Pp. 207-235 in Advances in Group Processes, Vol. 9, edited by Edward Lawler, Barry Markovsky, Cecilla Ridgeway and Henry Walker. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Wellman, Barry and Scot Wortley. 1990. "Different Strokes From Different Folks: Community Ties and Social Support." American Journal of Sociology 96 (November): in press.

Wellman, Beverly. 1991. "Pathways to Back Care." Master of Science thesis, Department of Behavioural Science, University of Toronto.

Woffers, Ivan. 1988. "Illness Behaviour in Sri Lanka: Results of a Survey in Two Sinhalese Communities." Social Science and Medicine 27:545-552.

Young, James Clay. 1981. Medical Choice in a Mexican Village. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Zborowski, Mark. 1952. "Cultural Components in Responses to Pain." Journal of Social Issues, 8:16-30.

Zola, Irving K. 1966. "Culture and Symptoms: An Analysis of Patients' Presenting Complaints." American Sociological Review 31:615-30.

Zola, Irving K. 1973. "Pathways to the Doctor: From Person to Patient." Social Science and Medicine 7:677-89.

ENDNOTE

1. I suspect that there has been little financial support for such research because of the unwillingness of the medical establishment to recognize alternative practitioners as worthy of study. By contrast, studies of traditional Third World traditional health care fit within well-established ethnographic genres and studies of North American lay care is acceptable for study as either (a) a barrier to "proper" medical care or more recently, (b) a low-cost substitute or adjunct to such care (Gottlieb and Selby 1990).

2. Given this procedure, I cannot be sure whether some people refused to participate in the study although practitioners told me that almost all agreed when asked. The lack of a random sample inhibits generalization from my data to the general population of low-back pain sufferers.

3. The data show no significant differences in age between the physician, chiropractic and Alexander clientele. The lack of older age respondents might reflect some sampling bias on the part of physicians or self-selection, but it is more likely that low back pain disorders may be less important in the rank of complaints that older persons present to their physicians (Verbrugge, 1986).

4. They all have at least a high school education or above with two-thirds sample having attended university for a minimum of two years. This is slightly higher than that reported in other studies (Kelner, et al., 1980; Coulter, 1985), and it may be a result of the high-SES locations of their chiropractors.

5. There is a complete lack of scholarly research into the profession of being an Alexander teacher. There are no published studies that examine the number of certified teachers practising the technique, what practices are like, who their clients are, and how the clients got there (Hamilton, 1986).

6. I asked the participants if they did "anything in the area of health prevention or health maintenance", and I listed 20 different kinds of activities.

7. Information about the strength of ties was obtained by asking participants to describe how close they were with each network member.

8. Percentages add to more than 100% when persons have identified more than 1 person initially. For example, one woman who had an accident while body surfing spoke initially with her husband and her friends, all of whom had been present at the accident.

9. The high number of surgical procedures is not surprising as 8 medical clients were the patients of orthopedic surgeons. In cases where the family doctor or another medical practitioner was the primary caregiver, surgery was used less often.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I appreciate the advice and support provided to me by Merrijoy Kelner, Victor Marshall, Barry Wellman, the Department of Behavioural Science and the Centre for the Studies of Aging, University of Toronto.

|

|