![]()

-

Chapter 8

Partners in Ilness: Who Helps When You Are Sick [1]

Beverly WellmanIn Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Challenge and Change edited by Merrijoy Kelner, Beverly Wellman. Harwood Academic Publishers, a subsidary of Taylor & Francis, 2000

Identifying Health Care Supporters in the Community

Since the 1960s, sociologists and anthropologists have been interested in the association between the use of medical services and the influence of family, friends and others on health care choices (Mechanic 1968; Suchman 1965; Kleinman 1980; Ryan 1998). Kadushin (1966) found that the use of psychiatric services was associated with membership in an informal social circle that was supportive of psychotherapy. Patients who belonged to such a circle were more likely to receive support, advice and encouragement, compared to the clinic patients who were not members of a psychiatrically oriented informal group.

While some researchers have argued that the presence of everyday symptoms of illness is not necessarily sufficient to bring a person to medical care (Alonzo 1979; Coe et al. 1984; Levanthal and Hirschman 1982), others have noted the important influence of family, friends and others on the process of seeking care (McKinlay 1972; Salloway and Dillon 1973; Pescosolido 1986, 1992). Such scholars have discovered empirically that who one talks to influences what one does, and particularly, what course of action is taken to resolve health problems (Pescosolido et al. 1998). For example, McKinlay (1975) found that those people whose social networks were composed primarily of family tended to be underutilizers of health care, while those whose social networks were composed primarily of friends tended to be heavy utilizers of medical care.

On a more general level, Friedson (1960) identified the importance of the "lay referral system"; Kleinman (1980; Kleinman, Eisenberg and Good 1978) described how the "popular sphere" (members of one's community) influenced health, and Chrisman and Kleinman (1983) expounded upon the interrelationship between the use of the popular sphere, the "professional" sector (Western medicine) and the "folk" sector (complementary and alternative therapies) in the quest for health care. Yet despite these documented overlaps and linkages between the popular, professional and folk sectors, most scholars have tended to analyse the use of a single sector, the professional sphere. In chapter ten, Pescosolido discusses the Network Episode Model which takes a broad perspective on how people find their way into various treatments. It focuses on the social influences exerted by community members on the dynamic process of dealing with emotional and physical health problems. Adopting a network analytic approach has made it possible to broaden the focus and ask patients from a variety of modes of treatment to tell us who were the people they depended on for support and information for their health concerns, and ultimately their health care choices. This is the model used in the research reported here.

The key question posed was: To whom do patients involved in various treatment modalities turn when they have a health problem? The research looked at the patients of four different kinds of alternative practitioners (chiropractors, acupuncturists/traditional Chinese medicine doctors, naturopaths and Reiki healers) as well as the patients of family physicians (called general practitioner in the UK and primary care givers in the USA). It examined the ties that provided three major kinds of health support: 1) talking about health (i.e., health confidants), 2) giving general information about health, and 3) giving specific information about alternative therapies and practitioners. The main objective was to explore the support and information that patients received from family and friends, as well as from practitioners. In this connection, scholars have shown that not all network members are supportive, and that among those network members who are supportive, different members provide different kinds of support (Wellman and Wellman 1992). Although ties with health-care professionals (physicians) are included in the analysis, previous research (Eisenberg et al. 1993, Wellman 1995) has shown that patients are not learning about alternatives to conventional medical care from their physicians. Using a network approach and not pre-defining who the health information providers would be, made it possible to discover and describe how health support flowed to patients in this study from their social networks, and subsequently to identify how some patients found their way to complementary and alternative medicine practitioners. For example, while spouses provide a wide range of support compared to network members outside the household (Wellman and Wellman 1992), friends and family members each tend to provide different kinds of support (Wellman and Wortley 1989, 1990).

Interviewing patients from five treatment groups, made it possible to examine the linkages between 300 Toronto-area patients and their 1344 health ties (See Kelner and Wellman 1997a and 1997b for detailed information on sample selection.). The fundamental problem was to disentangle what types of ties were associated with which kinds of health support for patients in each of the five treatment groups. A secondary goal, but nonetheless germane to the study, was to assess the importance of:

- The strength of ties, from very close intimates to acquaintances. "Strong ties" were measured by asking patients to tell us how close they felt to the person giving them support. The scale ranged from 1 (extremely close) to 5 (acquaintance only, not close at all). Given the research objectives and large data set, the five categories were collapsed into three: very close, close and acquaintance.

- The basis of the relationship, be it kinship, friendship, family physician, or alternative practitioner. In response to the original question, "Who do patients turn to when they have a health problem?", all of the relational responses to the health support questions were grouped into four categories that reflected the informal, professional and folk sectors: kin, friends [2], physicians and alternative practitioners.

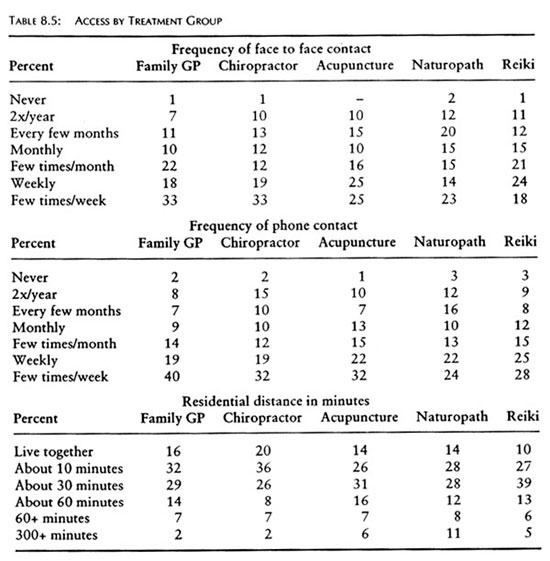

- The access that patient and network members have to each other. Access or frequency of contact was measured by: frequency of face-to-face contact, frequency of phone contact and residential distance from one another. Frequency of face-to-face and phone contact were measured on a scale ranging from 182 ("a few times per week") through 52 ("weekly"), 12 ("monthly"), 2 ("2 times per year") to 0 ("never"), with gradations in between. Distance was measured in minutes from 0 ("same residence") to 400 ("more than 5 hours away"), with meaningful time distances in-between.

In essence, we asked if the patients of family physicians had more family members and fewer alternative practitioners in their networks than the patients of CAM practitioners? By examining the relationships of supportive health networks for each treatment group, it was possible to reach a conclusion to this question,

The Strength of Ties

Granovetter (1973) provides a useful way of understanding how some patients moved from informal to conventional medical care to alternative care. He argues that it is weak ties - not strong ties [3]- that are important for the diffusion of information. Whereas strong ties tend to be found between persons who are members of the same social circle, weak ties tend to be found between socially dissimilar persons, which gives them access to more diverse social circles. Hence, Granovetter argues, weak ties transmit a greater range of information.

In support of Granovetter's weak ties argument, Weimann (1982, p. 769), in his study of communication flows, notes the importance of "marginals" as "bridges" or "importers" of new information. Nevertheless, strong ties are often more supportive and persuasive (Wellman and Wortley 1990; Wellman 1992). For example, Lee (1969) and Badgley, Fortin-Caron and Powell (1987) found that many women used ties with close friends and family as key sources of information for locating (then illegal) abortionists.

Therefore, we examined the relationship between the strength of a tie, the type of treatment a patient was in, and the type of support given. For example, did people who have strong ties become health confidants for family physicians? Did people who have weak ties provide information about alternative practitioners? We expected that weak ties would predominate in providing information about alternative practitioners - because information about them is not widely known - while strong ties would predominate in providing support and information about the more established treatments of family physicians and chiropractors. For example, the prediction for Reiki clients would be that they would have the largest networks of all five groups of patients, and by extension, a larger proportion of their networks would be comprised of acquaintances (weak ties). Furthermore, given that Reiki therapy is relatively unknown, not popular, and not reimbursable from the state or private insurance, one should expect to find support for Granovetter and Weimann's arguments about weak ties as bridges to Reiki and Reiki practitioners [4].

Basis of Relationship

Where did a majority of supportive information come from; the popular, medical and/or folk (CAM) sectors? Many health care professionals are aware that much of the health information their patients acquire comes from the lay public, including the Internet. In this study, we differentiate between family and friends. Research has shown that family- especially close family- tend to be supportive (Pratt 1976). People have a normative claim on their relatives' help in dealing with taxing health situations, and densely-knit kin networks are structurally connected so that members can learn about health problems and mobilize collective support (Wellman 1990). Yet friends may tap into more diverse social circles and hence, be more apt to know about alternative forms of health care.

To recognize the importance of family and friends in health networks is not to downplay the importance of health care practitioners in such networks. They can serve as confidants, sources of information, and sources of referral to other practitioners. But the situation is not symmetric for physicians and alternative practitioners. For one thing, alternative practitioners (except for chiropractors) have no officially recognized status, and their fees are not covered by the government's health insurance plan. Moreover, many physicians have a low regard for alternative therapies, while CAM therapists have been shown to have more mixed and more accepting opinions about physician-based medicine (Wellman 1995; Kelner, Hall and Coulter 1980). This suggests, on the one hand, that family physicians will be substantial participants in the networks of their patients, but CAM practitioners will not be members of these networks. On the other hand, we predict that both family physicians and CAM practitioners will be substantial participants in the networks of patients who use CAM therapies.

Access

Information, advice and support about health can only be provided if the giver and the recipient are in communication with each other. Such communication is also the principal means by which network members learn about each other's health problems. In addition, the more that people are in contact, the more likely they are to empathize with each other (Homans 1961). Wellman and Wortley (1990) have found that the supportiveness of such contact is independent of the strength of the tie and the basis of the relationship. In other words, the more contact that network members have, the more health support they can be expected to provide.

The physical proximity of network members may also matter, despite the communication facilitated by the telephone and the Internet (Wellman and Tindall 1993). It has been demonstrated that communication media are never a total substitute for the full range of communication that face-to-face contact provides (Wellman and Gulia 1999). This is an especially important consideration when people are communicating about delicate matters of health. Moreover, physical proximity means that network members can more easily provide concrete health care.

Gathering a Health Network Sample

The information on health ties comes from the patients' responses to the following four questions:

(1) Who do you talk to when you have problems with your health?

(2) Who, if anyone, gives you information about health in general?

(3) Who, if anyone, gives you information about alternative health care practitioners?

(4) Who, if anyone, gives you information about alternative therapies?

For each question, patients were asked to name a maximum of three persons. The responses to the questions on information about therapies and practitioners were combined in order to simplify the complex management of data and also because the responses to the two alternative support questions tell a similar story. In total, three hundred patients spoke about 1,344 people who were important to their health histories [5].Studying Health Ties in Metropolitan Toronto

The patients came from all parts of Metropolitan Toronto, a city with a population of more than three million people. While most of the patients in this study were Canadian and European, the city is ethnically diverse and multicultural. "Institutionally complete" ethnic communities tend to take care of their members' health needs by using physicians and other health care practitioners who come from their own ethnic group (Breton 1964). This means that a variety of alternative therapies and therapists which are particular to certain ethnic communities are available to everyone else in the city. The patients we interviewed reflected the cosmopolitan nature of Toronto, They came from a variety of backgrounds and displayed a variety of patterns for obtaining help for their health problems. Had English not been a requirement, the percentage of foreign born would have been higher.

Patient Characteristics

The three hundred patients in this study exhibited different kinds of social characteristics, depending on the type of health care they were currently using. The characteristics highlighted here are the ones that are relevant to their health network behaviour. In the case of gender, women were in the majority in all five of the treatment groups. Their percentage was highest among patients who were using acupuncture/traditional Chinese medicine (70%), naturopathy and Reiki (85%) and lowest among patients of chiropractors (58%). In terms of age, the highest mean age was found among the patients of family physicians (m=56, md=60 and the lowest mean age was found among the patients of chiropractors (m=40, md=37). Echoing the research of scholars here and in other countries (Astin 1998, Eisenberg et al. 1998; Furnham and Smith 1988; Sharma 1995), the data here show that CAM patients were well educated. In fact, they were better educated than the patients of family physicians, and Reiki patients had achieved the highest educational level of any of the groups (88% had university degrees). In addition, these CAM patients were also more affluent than family physician patients; Reiki patients earned the highest income of all (51% earned at least $65,000 per year).

Health Problems

CAM patients reported more about chronic problems than did the patients of family physicians, who said they saw their doctors for more acute kinds of problems such as cardiovascular conditions as well as diagnosis and monitoring. Not surprisingly, chiropractic patients consulted their practitioners almost entirely for musculoskeletal problems. Other differences between groups were minimal, although more patients used Reiki for emotional problems than any other patients.

Patients' Health Ties

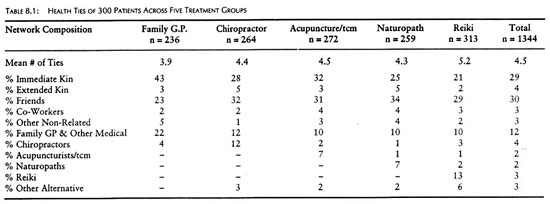

CAM patients had more health ties to members of their social community than did patients of family physicians (Table 1). In other words, these patients had more people in their social networks with whom they could discuss health issues. Of all the CAM groups, Reiki patients had the highest number of health ties (mean=5.2) compared to family physician patients (mean=3.9). It is worth noting that more than half of the health ties for each of the treatment groups were female (family physician ties= 55%, chiropractic ties=52%, acupuncture/tcm ties=62%, naturopathy=59%, and Reiki=71%).

A majority of the health ties were the people who are referred to here as 'health confidants' (i.e., the people with whom patients talked when they had a health problem). For all groups of patients in the study, health confidants constituted approximately half of their total health ties. When patients were asked who gave them general advice and information about health, the percentages were slightly lower. About one third of all health ties in all treatment groups provided such information. Information about CAM practitioners and CAM therapies was provided even less frequently by any of the patients' health ties. Less than one fifth of family physician patient ties provided any information in this regard as compared to less than a quarter for chiropractic patients, and about one quarter for the other CAM patients.

Tie Strength

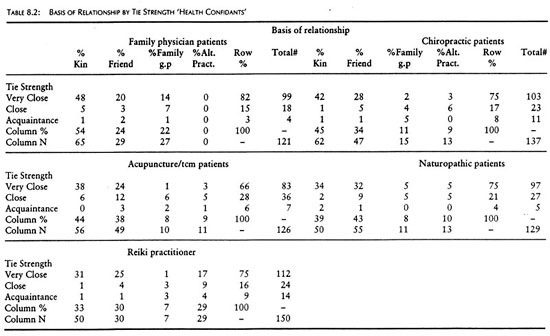

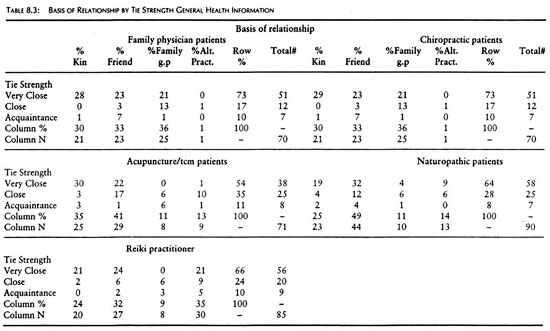

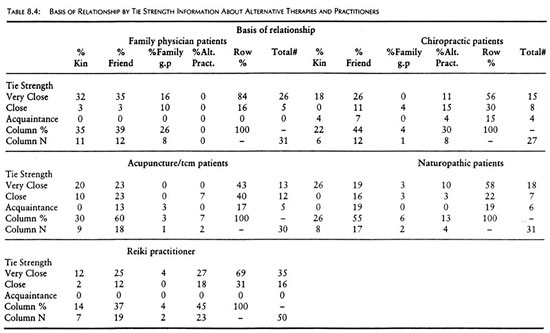

Most people that these patients talked to about their health were people that they felt close to, and with whom they had strong ties. This was especially true of the family physician patients (Table 8.2). CAM patients also reported many strong ties among the people they talked with about their health, but acquaintances played a somewhat stronger role in this than they did for the family physician patients. The pattern varied modestly with the type of health support provided, although in almost all cases strong ties predominated. For general health information, the picture did not vary by treatment group (Table 8.3), The patients were getting it from people to whom they felt close. Even when it came to receiving information about specific alternative practitioners and therapies, most of the patients still relied on their close ties (Table 8.4). In fact, family physician patients and Reiki patients received no information of this kind from acquaintances, while the other three groups received only a small amount of this kind of information from acquaintances

Relational Basis of Support

Health ties were mainly with family and friends (Table 1). In the case of patients of family physicians, family members comprised almost half (46%) of the health ties who provided some type of health support, while friends comprised almost one third of ties (30%). Similarly, family also played an important role for CAM patients, but friends generally provided an even larger amount of support and information. For example, in the case of naturopathy, friends and other lay persons comprised 42% of their health ties, for acupuncture/tcm it was 38% and for Reiki 34%. Indeed, friends comprised at least one third of the health ties for all CAM patients, regardless of treatment group.

When examining health ties from the professional sector, the findings were that all treatment groups had health networks comprised of medical doctors. Major differences existed, however, between the patients of family physicians and all CAM patients. Almost one quarter (22%) of the health ties of family physician patients were with medical doctors, whereas they constituted only about 10% for all other CAM groups. By comparison, CAM patients reported health ties with other alternative practitioners but not to the same extent as family physician patients with their doctors. Once again Reiki patients provided an exception to the other CAM patients. They had health ties with several different types of alternative practitioners as well as with family physicians.

Moreover, the different kinds of relationships provided varying types and amounts of support. When looking at the people who were health confidants, it was apparent that very close family and friends constituted most of these networks (Table 2). For family physician patients, health confidants were drawn primarily from family (54%), particularly close family members (48%) whereas for CAM patients, friends played at least as great a role if not more so. What is distinctive about the Reiki patients in this respect is that their close friends included alternative practitioners (17%) who served as health confidants.

The patterns were fairly similar, but the percentages were slightly lower for people who provided general health information. Most of it came from very close family and friends too (Table 3); only in the case of Reiki are alternative practitioners mentioned often in this respect. For chiropractic patients, just over one third (36%) of their health information came from family physicians. The rest of the CAM patients also reported receiving health information from family physicians, but to a considerably lesser extent.

Information to patients about alternative practitioners and therapies came from a small subset of their patients' social networks. In fact, among family physician patients, almost no information about CAM came from any member of their network. The only CAM therapy that they mentioned was chiropractic and the information about this stemmed from very close or close family and friends. For the CAM patients, this kind of information was also provided by the people they knew and trusted (Table 4). This is true for all CAM groups, but in the case of Reiki, the sources of information included other close/very close alternative practitioners as well as family and friends.

Frequency of ContactIt is not surprising that the health ties of these patients were people with whom they were in contact on a fairly regular basis. They tended to see them frequently, talk to them often on the telephone and live within close proximity (Table 5). Once again, family physician patients were different from the CAM groups, in that they had more frequent contacts with their health ties. The profile for all CAM groups looked fairly similar; approximately two-thirds of these patients saw or spoke to their health ties frequently and about three-quarters of them lived in the same residential area and some even lived in the same house..

DiscussionSomeone to Talk To

The patients in this study did not lack for people to talk to about their health, nor did they lack health informants. Almost everybody mentioned someone; in only two cases did patients say they did not speak with anyone about their health. A typical network contained two family members, one or two friends, and one practitioner (physician or alternative). Yet, there was one major difference between patients of family physicians and patients of CAM practitioners: the size of the networks. Family physician patients had the least number of ties available for support, compared to the clients of Reiki who had the greatest number of health ties. The number of patient ties of people who used chiropractors, acupuncturists/traditional Chinese medicine doctors and naturopaths fell in between these two extremes.

Beyond that, a similar pattern was evident for the five treatment groups. Most of their ties were made up of health confidants: people with whom patients discussed their health problems. Fewer ties served as sources of health information, and even fewer provided advice and information about CAM therapies and practitioners. A typical patient had two confidants and one network member who provided general health information. Fewer people had networks that could provide them with information about alternative therapies and practitioners. (Reiki was the only exception: Almost every network had someone who could advise patients on alternative therapies and practitioners.) This low representation of providers of information about CAM may be a result of the fact that the data were collected in 1994-95; a time when the use of CAM had not yet spread so expansively to the larger population (see Valente, chapter seven).

More than half of the health ties of the patients of acupuncture, naturopathy and Reiki were with women. Indeed, women formed the great majority of Reiki ties. Given that many more women than men were patients of acupuncture/traditional Chinese medicine, naturopathy and Reiki, the predominance of women was not surprising. It may also be that women discuss and exchange information about health and health care more frequently than men, thus accounting for the predominately female composition of the health ties.

Patients revealed modest but real variations in their health networks depending on the type of health care provider patients were consulting. The networks of physician patients were made up almost entirely of family and friends, with some representation by physicians. Only one family physician patient mentioned an alternative practitioner in their health network. Similarly, the networks of CAM patients were also made up almost entirely of family and friends. Yet, all the CAM groups of patients had physicians in their networks, showing that the use of CAM did not imply that patients had turned their backs on physicians; Finding that has been demonstrated in a number of other studies (Crellin, Andersen and Connor 1997; Eisenberg et al. 1998; Vincent and Furnham 1997). Only in the extreme situation of Reiki, did clients have many alternative practitioners in their networks.

But more importantly, regardless of the treatment group from which the patients in this study came, and the sectors represented in their networks, strong ties predominated in these health networks. Strong ties consisted not only of health confidants but they were also the ties that provided the patients in this study with general health information as well as specific information and advice about CAM practitioners and therapies. Granovetter's view on the function of weak ties providing new and diverse information was not supported here. Health seemed to be too important a matter to be dealt with by others who were not considered intimates. In short, health networks consisted of small networks of strong ties. This finding makes it clear that when it comes to health, people turn for support and information to their dearest and nearest.

Although Reiki clients had a higher percentage of acquaintances in their networks than other treatment groups, they too had a majority of strong ties in their networks. Why was it that acquaintances were not more influential, especially in the case of Reiki clients where, based on the strength of weak ties argument, we expected that they would play a stronger part? The explanation may lie in Friedson's concept of the lay referral group, and who people take seriously when they make inquiries about health and health care. Since health is an important and serious matter, people tend to rely on those they know and trust, (i.e., their strong ties). The patients in this study chose not only to confide in their close ties, but also to glean much of their information from these close relatives and friends (including some physicians and alternative practitioners). Acquaintances may have given them ideas about types of therapies and who to consult, but these suggestions required confirmation and legitimation from close ties in order to be taken seriously.

In support of Friedson (1960) and Chrisman and Kleinman (1983), the data show that different patients turned to different types of people in the various health care sectors for support and information. Patient ties of family physicians came mainly from the informal sector (family and friends) and to a lesser extent from the professional sector (physicians). Hardly any ties emanated from the folk sector (alternative practitioners). By comparison, the four alternative groups had health ties emanating from all three sectors: informal, professional and folk. But despite having ties emanating from the folk sector, these varied according to the type of CAM therapy they were using. For example, patients of chiropractors had health ties mainly with chiropractors, but hardly with anyone else. At the other end of the spectrum, Reiki clients had the most health ties with people from the folk sector. Their ties were not only with multiple Reiki practitioners but also with naturopaths, acupuncturists/traditional Chinese medicine doctors, chiropractors and several other types of alternative practitioners.

The health networks of all five treatment groups were embedded in family, especially immediate family. Strong ties with family members provided the most assistance and information for all types of patients, but especially for the patients of family physicians who had fewer weak ties in their networks. Next in importance came strong ties with friends. As expected for patients of family physicians, those physicians described as (very) close to them were also influential in their health care. Also as expected for Reiki clients, the CAM practitioners whom they regarded as (very) close influenced their health behaviour. Yet, contrary to expectations, CAM practitioners were not substantial components of the health networks of chiropractic, acupuncture, or naturopathic patients.

Being close also meant that patients of all groups usually lived near many of their health ties, saw them regularly, and spoke often by telephone. Access probably did have an indirect effect on support, for frequent contact and proximity helped keep strong ties strong and available to provide health support. Without access, strong ties could not exert an influence on health matters. Health confidants and providers of information and advice are needed on a regular basis and ready access is crucial.

Conclusion

The analysis presented here is one of the first attempts to use social network analysis to examine how people come to use alternative types of health care. We know that friends and family are important reference points in the search for health care; we also know that physicians have been a secondary although important source of support, information and advice. What we have not been able to ascertain until now is what kinds of people give specific kinds of support, and the extent to which the patients of physicians differ from the patients of alternative therapists. Are there overlaps in the sources of advice given? And does it make a difference if the people turned to are socially close or merely acquaintances?

We have found appreciable similarities in the health networks of physicians' patients and CAM patients. All their networks were small, and based on strong, informal ties with family and friends. With the exception of Reiki patients, all the patients in this study have about the same percentage of ties with physicians as they do with alternative practitioners. This suggests the intertwining of networks leading to physicians and to alternative therapies: the modalities of treatment are linked and often simultaneous, rather than separate and sequential.

The differences found suggest that those with somewhat larger, more diverse networks are more apt to be involved with alternatives. The larger the network and the greater the participation of friends, the more alternative therapies will be used. Although these networks are not built on weak ties, Granovetter was right in conjecturing that large, diverse networks provide a wider range of opportunities - in this case, leading patients to treatment options beyond the medical model. This was certainly the case for the Reiki patients whose high incomes and educational levels help to determine the breadth of their networks and the abundant information those networks provide. While these findings are derived from a sample of Canadian users of CAM, they are not bound by geographic location. Indeed, the same patterns are likely to be found in the United States, Britain and elsewhere.

This work represents an initial effort to identify who people turn to for specific kinds of health information and advice. It does not address the equally important considerations of who people in treatment turn to for emotional support, or for more concrete kinds of support such as financial help, assistance with tasks of daily life, and small health care services. Future research using network analysis has the potential to reveal the full range of health care supports that are available to protect health and manage health care.

ReferencesAlonzo, Angelo. 1979. "Everyday Illness Behaviour: A Situational Approach to Health Status Deviations." Social Science and Medicine 13:397-404.

Astin, John. 1998. "Why People Use Alternative Medicine: Results of a National Study." Journal of the American Medical Association 279:1548-53.

Badgley, Robin F., Fortin-Caron, Denyse and Marion G. Powell. 1987. "Patient Pathways: Abortion." Pp. 159-171 in Health and Canadian Society: Sociological Perspectives, 2nd ed. Edited by David Coburn, Carl D'Arcy, George Torrance and Peter New. Markham, Ont.: Fitzhenry and Whiteside.

Breton, Raymond. 1964. "Institutional Completeness of Ethic Communities and the Personal Relations of Immigrants." American Journal of Sociology 70:193-205.

Chrisman, Noel, and Arthur Kleinman. 1983. "Popular Health Care, Social Networks, and Cultural Meanings: The Orientation of Medical Anthropology." Pp. 569-590 in Handbook of Health, Health Care and Health Professions, edited by David Mechanic. New York: Free Press.

Coe, Rodney, Frederick Wolinsky, Douglas Miller, and John Prendergast. 1984. "Social Network Relationships and Use of physician Services: A Reexamination." Research on Aging 6:243-256.

Crellin, .J.K., R.R. Andersen, and J.T.H. Connor. 1997. Alternative Health Care in Canada. Toronto: Canadian Scholars' Press.

Eisenberg, David M., R.B. Davis, S. L. Ettner, S. Appel, S. Wilkey, M. Van Rompay, and R.C. Kessler. 1998. "Trends in Alternative Medicine Use in the United States, 1990-1997: Results of a Follow-Up National Survey." Journal of the American Medical Association 280:1569-75.

Eisenberg, David M., Ronald C. Kessler, Cindy Foster, Frances E. Norlock, David R. Calkins, and Thomas L. Delbanco. 1993. "Unconventional Medicine in the United States: Prevalence, Costs and Patterns of Use." New England Journal of Medicine 328:246-252.

Friedson, Eliot. 1960. "Client Control and Medical Practice." American Journal of Sociology 65:374-382.

Furnham, Adrian and Chris Smith. 1988. "Choosing Alternative Medicine: A Comparison of the Beliefs of Patients Visiting a General Practitioner and A Homeopath." Social Science and Medicine 26(7):685-89.

Granovetter, Mark. 1973. "The Strength of Weak Ties." American Journal of Sociology 78:1360- 80.

Homans, George. 1961. Social Behaviour: Its Elementary Forms. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Kadushin, Charles. 1966. "The Friends and Supporters of Psychotherapy: On Social Circles in Urban Life." American Sociological Review 31:786-802.

Kelner, Merrijoy, Oswald Hall, and Ian Coulter. 1980. Chiropractors, Do They Help? Toronto: Fitzhenry and Whiteside.

Kelner, Merrijoy, and Beverly Wellman. 1997a. "Health Care and Consumer Choice: Medical and Alternative Therapies." Social Science and Medicine 45:203-212.

Kelner, Merrijoy, and Beverly Wellman. 1997b. "Who Seeks Alternative Health Care? A Profile of the Users of Five Modes of Treatment." Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 3:1-14

Kleinman, Arthur. 1980. Patients and Healers in the Context of Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kleinman, M., L. Eisenberg, and B. Good. 1978. "Culture, Illness and Care." Annals of Internal Medicine 88:251-58.

Lee, Nancy Howell. 1969. The Search for an Abortionist. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Leventhal, Howard, and Robert S Hirschman. 1982. "Social Psychology and Prevention." Pp. 183-226 in Social Psychology of Health and Illness, edited by G.S. Sanders and J. Suls. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

McKinlay, John. 1972. "Some Approaches and Problems in the Study of the Uses of Services: An Overview." Journal of Health and Social Behavior 13:115-152.

McKinlay, John. 1975. "The Help-Seeking Behavior of the Poor." in Poverty and Health, edited by J Kosa and I Zola. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Mechanic, David. 1968. Medical Sociology. New York: The Free Press.

Pescosolido, Bernice. 1986. "Migration, Medical Care Preferences and the Lay Referral System: A Network Theory of Role Assimilation." American Sociological Review 51:523-540.

Pescosolido, Bernice. 1991. "Illness Careers and Network Ties: A Conceptual Model of

Utilization and Compliance." Advances in Medical Sociology 2:161-84.Pescosolido, Bernice A. 1992. "Beyond Rational Choice: The Social Dynamics of How People Seek Help." American Journal of Sociology 97:1096-1138.

Pescosolido, Bernice A., Carol Brooks Gardner, and Keri M. Lubell. 1998. "How People Get Into Mental Health Services: Stories of Choice, Coercion and "Muddling Through" from "First - Timers"." Social Science and Medicine 46:275-286.

Pratt, Lois V. 1976. Family Structure and Effective Health Behavior: The Energized Family. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Ryan, Gery W. 1998. "What do Sequential Behavioural Patterns Suggest about the Medical Decision-Making Process?: Modeling Home Case Management of Acute illnesses in a Rural Cameroonian Village." Social Science and Medicine 46:209-225.

Salloway, Jeffrey, and Patrick Dillon. 1973. "A Comparison of Family Networks and Friend Networks in Health Care Utilization." Journal of Comparative Family Studies 4:131-42.

Sharma, Ursula. 1995. Complementary Medicine Today: Practitioners and Patients London: Routledge.

Suchman, Edward A. 1965. "Stages of Illness and Medical Care." Journal of Health and Human Behaviour 6:114-128.

Vincent, Charles and Adrian Furnham. 1997. Complementary Medicine: A Research Perspective Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Weimann, Gabriel. 1982. "On the Importance of marginality: One More Step into the Two-Step Flow of Communication." American Social Review 47(December):764-73.

Wellman, Barry. 1990. "The Place of Kinfolk in Personal Community Networks." Marriage and Family Review 15:195-228.

Wellman, Beverly. 1995. "Lay Referral Networks: Using Conventional Medicine and Alternative Therapies for Low Back Pain." Pp. 213-238 in Research in the Sociology of Health Care, Volume 12 edited by Jennine J. Kronenfeld. Greenwich, Conn: JAI Press.

Wellman, Barry, and Milena Gulia . 1999. "A Network is More than the Sum of Its Ties: The Network Basis of Social Support." Pp. 83-118 in Networks in the Global Village edited by Barry Wellman. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Wellman, Barry, and David Tindall (Eds.). 1993. "How Telephone Networks Connect Social Networks." Progress in Communication Science 12:339-42.

Wellman, Beverly, and Barry Wellman. 1992. "Domestic Affairs and Network Relations." Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 9:385-409.

Wellman, Barry, and Scot Wortley. 1989. "Brother's Keepers: Situating Kinship Relations in Broader Networks of Social Support." Sociological Perspectives 32:273-306.

Wellman, Barry, and Scot Wortley. 1990. "Different Strokes From Different Folks: Community Ties and Social Support." American Journal of Sociology 96:558-588.

ENDNOTE

[1] Research for this paper has been supported by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada. I appreciate the advice and assistance supplied by Sivan Bomze and Barry Wellman. The "we" used throughout this text reflects the close collaborative relationship I have with Merrijoy Kelner. This is a single-authored paper that is a product of our joint work.

[2] "Friends" includes network members identified as neighbours and coworkers. As almost all such ties were strong ties, we felt comfortable grouping them with friends per se.

[3] Granovetter defines strong ties as having frequent contact, emotional intensity, feelings of intimacy, embeddedness and reciprocal social support.

[4] In Canada, patients who use conventional medical services are reimbursed by the government and patients neither see a bill nor have to fill out administrative forms..

[5] Based on the information for each tie, a data set was created for the 300 patients and 1,344 health ties. Each patient tie had an identification number that was linked with the patient identification number. This enabled us to link information about ties and networks. The information collected for each tie such as relationship, gender, closeness, length of time known, frequency of contact and residential distance was coded and entered into SPSS/pc. The three questions which generated the names of the network ties were coded dichotomously: getting or not getting support. Each of the three questions became our dependent variables, and we were able to use logistic regression to examine the relationship between tie relation, tie strength and tie support.

|

|