Kyrgyzstan, officially the Kyrgyz Republic, is a small, landlocked and predominantly mountainous country in Central Asia; it was previously one of the 15 union republics of the Soviet Union, formally known as Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). Kyrgyzstan encompasses 198,500 square kilometres, bordering China to the east, Tajikistan to the south, Uzbekistan to the west and Kazakhstan to the north. Kyrgyzstan consists of seven oblasts (provinces): Batken, Chüi, Naryn, Osh, Jalal-Abad, Talas, and Yssyk Köl. Two-thirds of its population of five million live in rural and mountainous areas. Thus, the majority of people in Kyrgyzstan are involved in agriculture.

Kyrgyzstan is a multinational state; more than 90 nationalities and ethnic groups live in the country. The Turkic-speaking Kyrgyz, one of the most ancient people of Central Asia, constitute around 65 percent of the country’s population. The capital of the country is Bishkek, which has a population of about 790,900. However, according to unofficial sources, there are now more than one million people living in Bishkek, including many who moved recently from rural areas to engage in commerce.

Soviet rule was established in Kyrgyzstan between 1918 and 1922, and for more than 70 years Kyrgyzstan was an integral part of the USSR. Soviet rule aimed to abolish class-based human exploitation and to establish an equal society. As part of the Soviets’ grand scheme for the establishment of national republics in Central Asia, the Kara-Kyrgyz Autonomous Oblast was formed within the Russian Federation in October 14th, 1924. It then became the Kyrgyz Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic on February 1, 1926; and the Kyrgyz Soviet Socialist Republic (KSSR) on December 5, 1936.

The Kyrgyz developed their systematic written language during the time when it was part of the USSR (Though, the Kyrgyz used runic written scripts before as well). The written alphabet was first developed on the basis of Arabic script in 1924; then it was changed into Latin script in 1927. The Kyrgyz then shifted to the Cyrillic alphabet in 1940. The official announcement about the shift to Cyrillic claimed that the change of script was done in accordance with the sound peculiarities of Kyrgyz language and gave the Kyrgyz the opportunity to learn the Russian culture and gain access to Soviet and world literature.

Soviet attempts to integrate Kyrgyzstan into the USSR were reflected in people’s dress, personal behaviour, language, and modes of speech. Many Kyrgyz, particularly those who lived in urban areas, became deeply immersed in Russian (Soviet) culture and barely spoke their mother tongue. During Soviet rule, and especially from the 1960s on, many people became alienated from their Kyrgyz identities and become “Russified” in order to succeed economically. Later, during perestroika (re-building), the Kyrgyz intelligentsia referred to the process of “Mankurtisation”1 to denote the loss of national, ethnic, linguistic and cultural identities.

In addition, Kyrgyzstan’s population, like other citizens of the USSR, suffered from Stalin’s mass repression. Thousands of Kyrgyzstan’s intellectual and political elite were imprisoned and killed prior to World War II. They were falsely accused of being "nationalist reactionaries" and "anti-Soviet". Among those who were executed were such progressive members of Kyrgyz society as J.Abrakhmanov, K.Tynystanov, A.Orozbekov, P.Tynaev, and A. Sydykov.

World War II broke out in 1939; Kyrgyzstan, as an integral part of the USSR, began fighting against Nazi Germany from June 22 1941, when Germany attacked the USSR. The soldiers from Kyrgyzstan fought along other nationalities of the USSR, while older men, women and children contributed with their labour to defeat the enemy. After World War II, the USSR became involved in continuous Cold War and the continuous arms-race.

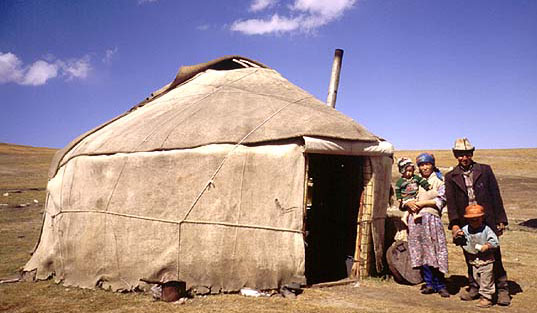

Major changes in the political life of the USSR started in the mid 1980s, when Mikhail Gorbachev introduced perestroika (re-building) and glasnost (public voicing) to overcome social, political and economical stagnation in the country. Because of perestroika and glasnost it also became possible to reflect on and re-consider the grey areas of the USSR history. People could openly discuss the negative aspects of the USSR in a manner not possible before. Historical information about huge human losses, population dislocations, and artificial divisions of territories during the establishment of the Soviet regime became publicly available. Other problems hotly discussed in Kyrgyzstan included disastrous changes in traditional identities and ways of life, forced collectivisation followed by mass arrests, and deportations, expropriation of the property of wealthy Kyrgyz families, ecological disruptions due to the building of irrigation systems for the mono-culture cotton industry in Central Asia, and imposed sedentarization of the nomad population.

Kyrgyzstan’s victims of Stalin’s repression were granted amnesty and then rehabilitated. Many mass graves of innocent victims were found. Many writers, poets and historians were rehabilitated and the ban on their work was lifted.

During perestroika, Kyrgyz people raised questions of preserving their historic heritage and mother tongue, and on September 23 1989, the Supreme Council of the Kyrgyz S.S.R. adopted a law "On a State Language" in which Kyrgyz was given the status of state language.

With perestroika and glasnost, people in Kyrgyzstan gained the rights of assembly and freedom of speech, the right to strike and the right to hold multi-candidate elections. However, the deteriorating economic conditions also increased resentment among the population. Such issues as religious extremism, ethnic rivalries and regional differences became more prominent.

Finally, the failed war in Afghanistan, economic, political and ideological battles with the capitalist world, and ineffective economic construction compounded by excessive misuse of natural resources (especially oil and gas) led to the collapse of the USSR.

The USSR broke up on December 7, 1991 and Kyrgyzstan became independent. Gaining independence aroused the hopes and aspirations of the people of Kyrgyzstan. The first president of Kyrgyzstan, Akaev, introduced an array of reforms, such as getting membership in international organisations, introducing a national currency (Som is the Kyrgyz national currency introduced on May 10, 1993), privatization, shifting from a monistic power structure to a pluralistic electoral system and moving from a centralised state economy to a market-oriented one. President Akaev gained international reputation as a reformer and he was the first leader of Commonwealth of Independet States to take his country into the World Trade Organisation in December 1998. Kyrgyzstan gained a reputation abroad as a leader of democracy in Central Asia; the term of "Island of Democracy" was popularly used to refer to the country. Understandably, all Akaev’s reforms were appreciated and supported by the Western countries.

Despite these growing hopes in the West, the USSR’s break-up was tragic for many people in Kyrgyzstan; it brought chaos, despair and uncertainty to the lives of thousands. Economic crisis, unemployment, poverty, dislocated civilians, poor living conditions, and various health problems have plagued Kyrgyzstan since the early 1990s. Kyrgyzstan’s economy found itself in a deep crisis: Industrial production declined by 63.7 percent from 1990 to 1996; agricultural output declined by 35 percent and capital investment by 56 percent. In 2001, a World Bank report indicated that 68 percent of Kyrgyzstan’s population lived on less than US$ 7 a month and the average annual salary was just US$ 165; the same report estimated a subsistence-level salary at US$ 295 a year. Between 1990 and 1996, Kyrgyzstan’s gross domestic product was almost halved, falling by 47 percent.

By Düishön Shamatov

1 It is "forgetting one’s roots", a term introduced by the Kyrgyz writer Chyngyz Aitmatov to denote the loss of national, ethnic, linguistic and cultural identities. Mankurt was a legend about a captive who was turned into a mental slave. According to the legend, certain nomadic people in old times used to take captive and clean shaved the head of that person and cover the head with a tight cap made of fresh skin from the udder of a camel. When the skin dried out, the cap tightened, the slaves suffered torments in the baking sun, and if they lived they lost their memories forever, could not even remember their tribe or their clan, and became stupid, hardworking and absolutely obedient. See Aitmatov’s (1988) novel "The day lasts more than a hundred years" for full description of the legend.