|

|

"But

I want to make a difference": Six novellas about teacher educators

and teacher education reform

Ardra L. Cole

Living

in Paradox: A Multimedia Representation of Teacher Educators' Lives in

Context

Ardra L. Cole, J. Gary Knowles, brenda brown

and Margie Buttignol

Dance

Me to an Understanding of Teaching

Ardra Cole and Maura McIntyre

Living

and Dying with Dignity: The Alzheimer's Project

Ardra L. Cole and Maura McIntyre

the

earthworm

Nancy Davis Halifax

Artistry,

Inquiry, and Sense of Place: Secondary School Students Portrayed in Context

J. Gary Knowles & Suzanne Thomas

Portraits

of Land and Sea & Arctic and Tropic

J. Gary Knowles & Suzanne Thomas

Images of September 11, 2001

Lisa Lipsett

On

Boxes and Words

Kathy Mantas

Reclaiming

the Real: Photographic Literacy and Historical Memory in Big Intervale,

Cape Breton

Amish Morrel

Holding

Flames

Eimear O'Neill

Landscapes of Embodiment and Moments of Re-enactment

Suzanne Thomas

"But

I Want to make a difference":

Six novellas about teacher educators and teacher education reform

(a fictional work in progress)

Ardra L. Cole

You will soon meet six members of the teacher education professoriate. They are what you might call 'typical' of teacher educators of this current generation at the turn of the new millenium. They are mostly women; all are of white European heritage; they range in age from early thirties to early fifties; they reflect a wide spectrum of personal relationships-lesbian, heterosexual, single, divorced, partnered, married; young children, grown children, grand-children, no children. All took up their tenure-track positions at different universities after many years of experience as classroom teachers, school administrators, curriculum consultants, special education/resource specialists, staff-, program-, and/or community-developers; many had several years experience teaching part- or full-time at a community college or faculty of education in a non-tenure track capacity. Without exception, they made career changes to become teacher educators, a move that had high associated costs. They did so because they wanted to and believed they could make a difference.

The teacher educators were hired, under various circumstances, at a time when teacher education (and public education in general) was once again under fire. Pressure from various sources for universities to better prepare teachers to work in a postmodern and pluralistic society so that teachers might assume more expansive roles in classrooms, schools, and communities; threats and realities of fiscal constraint in a socio-political context of conservative rationalism; and, an increased emphasis on performance and production characterise the prevailing conditions when they joined the ranks of the professoriate. Despite these and many other contextual challenges, they began their university careers with hope and optimism. They, like many before, and presumably to follow them, were convinced that they would be able to do their part toward changing a system of teacher education that was and is in dire need of revitalisation.

When you meet these six people, chances are you will think that you know them. You probably do, in the sense that there are likely to be strong points of connection, identification, resonance. It may seem as though you are reading about yourself, or someone you know, perhaps your colleague in the next office. But you don't really know these people because they are fictional characters born of research data and my imagination, an imagination illuminated by my own experiences as a university-based teacher educator. They are fictional out of necessity.

The stories reveal some terrible truths about the

academy and they powerfully elucidate how the university has remained

virtually unchanged in any substantial way for centuries. The stories

also reveal the strength of commitment and unabashed passion of those

who challenge the status quo; they are inspirational stories. For these

reasons, among others, the stories must be told. Their telling might,

in some small way, help us move forward as a profession and as a community

of scholars. But, telling these stories cannot and must not place individuals

at risk. Details and idiosyncratic complexities, which could surely identify

individuals and institutions, must be camouflaged. Particular events and

incidents, which both illustrate and reveal, must be presented carefully.

Circumstances must be changed. Aspirations, commitments, and strategies

that perhaps have remained covert must remain so, somehow; I cannot blow

anyone's cover.

back

to index

Living

in Paradox: A Multimedia Representation of Teacher Educators' Lives in

Context

by Ardra L. Cole, J. Gary Knowles, brenda brown and Margie Buttignol

The three installations which comprise this multimedia representation draw inspiration from the tableau art form particularly as interpreted by American contemporary artist Edward Kienholz (1927-1994). Kienholz' work incorporates all art forms and all manner of method and material. His use of multimedia is intended to fuse art into life in order to do away with the distinctions between artist and artisan and to enable us to see the various aspects of "truths". His raw, often shocking, realistic renditions are intended to make bold cultural and political statements allowing no room for the viewer to escape. According to Ruskin (1996, p. 43), Kienholz' art invites us "to judge our present social conditions and then we are begged, through a visual scream, to create another reality, one which celebrates human dignity". For Kienholz, the reality of human suffering is best expressed through art with the use of absurdity, exaggeration, or distortion which forces the viewer to become an active participant in the representation.

Living in Paradox was created from information gathered through interviews, e-mail exchanges, observations, and personal and professional writing in a three-year study of pre-tenured teacher educators working to change the way teachers are prepared in Canadian faculties of education. The paradoxical nature of much of their experience was an overarching theme from the research analysis as was their experience of struggle or conflict. Often, when talking about certain issues and experiences, words seemed woefully inadequate to convey the passion and emotion felt. Frequently, the teacher educators used graphic language to create images or metaphors to describe elements of their experiences. The power in their message could not be contained by or adequately communicated through printed words on a page. Hence, the creation of this multimedia representation. Following Kienholz, the images rely on shock value and exaggeration to draw viewers in, to connect with the truths expressed, and, hopefully, to precipitate the creation of a more humane and generous reality for teacher educators in the academy.

The process of engaging with and making sense of the teacher educators' experiences engendered the metaphors represented by and in the installations. Acknowledging the power of metaphor as a mode of communication and an analytic construct, it is our intention and hope that viewers will engage with the images with a transformative spirit, and commitment to change.

Installation 1: Academic Altarcations

Installation 2: Wrestling Differences

Installation 3: A Perfect Imbalance

Installation 1:

Academic Altarcations

media: common objects; clothing; wood; vinyl; metal; rubber; peau de soie; polyester batting; audio recorded text; acrylic paint on canvas; music, Canto Gregoriano, Coro de monjes del Monasterio Benedictino de Santo Domingo de Silos, 1973, EMI Records, S. A., Madrid, Spain.

One of the most striking and prevalent self-contradictory yet 'truthful' expressions made by the teacher educators is represented in this installation. It is the paradox of sacrifice.

The academy, it seems, is a sacred place held in high esteem because of the power it holds and grants to its worthy members. For those with aspirations and commitments to make a difference in the lives of students and teachers and, by extension, to better society, the academy is a place where that kind of influence is deemed possible. Such individuals with secure, well paying jobs in schools or other educational settings often leave those situations to take up positions as university-based teacher educators, usually for much less salary and little or no job security. Frequently, their quest for an academic life uproots them; they leave home and family. Sometimes they literally leave behind spouses and children; other disconnections might be more metaphorical. Once affiliated with the academy the desire to stay is so strong that they become increasingly self-sacrificing. Work becomes all encompassing, all consuming. Pressures to perform as teachers, researchers, scholars, and community members and personal ambitions to "make a difference" leave little time or room for life outside work, especially when those two sets of goals require different but equally demanding ways of working. Self-care is reduced to luxury and family commitments become a challenge to uphold.

The promise of the academy, though, is seductive. Despite the personal and professional sacrifices made religiously at the academic altar, often with considerable associated pain and loss, the chant resounds: "But I love my work. I really, really love my work".

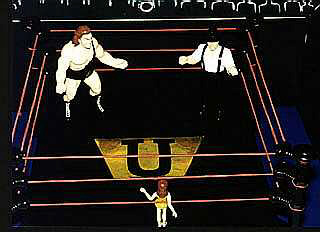

Installation 2: Wrestling Differences

media: plastic action toys; plastic; nylon; elastic; wood; acrylic paint; narrative text; slides

The academy, as a bastion of patriarchy built on norms and values of rugged individualism, competition, and hierarchy, is an adverse arena for many women faculty members. While the number of women holding full-time academic positions has increased in most areas of the university, in large part due to affirmative action policies and practices, the climate for women faculty in universities is still chilly. In education this is particularly ironic because education (along with other professional faculties such as nursing and social work) has been and continues to be perceived as women's work. Education faculties, as feminine structures with low standing in the academy, continue to struggle for acceptance as legitimate members of the academic community. Within education faculties women struggle both for acceptance by their male counterparts and against the norms and values upon which the dominant male culture is built (even in a feminized profession). For many women teacher educators, this is the paradox that defines their struggle.

Many of the messages women receive, when they make known their presence and difference, are in the form of subtle suggestions about how to become socialized and fit into the existing culture. The kind of political posturing and self-justification that go on at faculty meetings or the isolationist ways of working that are expected and rewarded are two examples. Some not so subtle messages serve as reminders to women of their proper place in the male-defined hierarchy, for instance, the kinds of roles to which women are assigned and the ways in which they are expected to assume their responsibilities in those roles. The woman faculty member who was invited to join a committee and then given the responsibility to make and serve coffee, and the one who chaired a labour intensive committee and was left to carry out all the very time consuming clerical work only to be succeeded the next term by a male faculty member who was provided full clerical support for the committee work are two blatant examples drawn from the many stories told by women teacher educators in this study. And then there is the invisible labour associated with field- and community-based work and guidance and support of students which counts for little in the academy but which takes up a large percentage of women faculty members' time and energy.

To challenge and change the status quo is a tiring and seemingly relentless struggle, sometimes with little visible gain. It is a sparring game that often involves men and women in an oppositional stance. The gendered nature of the academy presents particular problems for women in faculties of education where the arena of change extends from within the faculty to the broader university context.

Installation 3: A Perfect Imbalance

media: wood and metal, foam blocks

Teachers educators' work is a balancing act of activities, demands, obligations, commitments, and aspirations. The multiplistic and diverse nature of their work and the time and energy commitments involved in the elusive pursuit of a balanced professional life also makes a search for balance between the personal and professional realms of life a fruitless effort.

The dual mandate of teacher educators' work that requires them to serve both the academy and the profession keeps their gaze focused on the fulcrum of their lives striving for balance. Work and personal (self and family) commitments pull against one another. Time spent on teaching and field development activities must be kept in check so that sufficient time is available for research and writing. Decisions about the kind of research to engage in, where to publish, and for what purposes must take into account the different sets of values that define the profession and the academy. Aspirations and commitments to work collaboratively must be carefully monitored (even in spite of rhetoric that suggests otherwise) so as to live up to the university's standards of individualism, especially for purposes of tenure and promotion. A divergence in research interests must be curtailed in order to establish a specialized and unique program of research. Attitudes, values, and practices cannot be overly challenging of the status quo upon which all structures, policies, and norms are based.

The problem for most teacher educators, especially those committed to change in teacher education, is that no matter how hard they try the scales are impossible to balance because the weights are uneven to begin with. According to the values and standards of the university teaching, service, professional and community development, and other activities that have mainly local or personal implications and which demand inordinate time and energy commitments do not carry much weight. The heavy weights from the university's perspective are those activities which result in intellectual and financial prestige and international acclaim. For most teacher educators, it seems, any balance that is possible to achieve is always imperfect.

For more on the research project

Dance

Me to an Understanding of Teaching

by Ardra Cole and Maura McIntyre

PRELUDE

Dance Me to the End of Love (Leonard Cohen)

ACT I

CONSTRAINT

Dance: Drills

Narrative: Refrain

Music: Wizard of Oz

ACT II

Conflict

Dance: Steps Out of Time

Narrative: Arrhythmia

Music: You Gotta Change (All that Jazz)

Ghengis Dreams (Oliver Schroer)

Piano Concerto No. 1 in B Flat Minor Op. 23 (Tchaikovsky/Clayderman)

Common Threads (Bobby McFerrin)

ACT III

CREATIVITY

Dance: Improvisation

Narrative: Synchronicity

Music: Tha Mi Sgith (College of Piping Celtic Singers)

Mist Covered Mountains (Bill Gardens Scottish Orchestra)

Shake your Groove Thing (Peaches and Herb)

I Heard It through the Grapevine (Marvin Gaye)

Shake your Groove Thing (Peaches and Herb)

Finale

Dance Me to the End of Love (Leonard Cohen)

The above is taken from a program of a performance we wrote, choreographed, produced, and performed as a representational account of a collaborative self-study. The substantive focus of the inquiry was rooted in a persistent, self-observed incongruity between Ardra’s "style" of teaching (who she is as a teacher) and her "style" of learning (who she is as a learner). We wanted to augment conventional approaches to research with non-conventional methods in order to explore teaching and learning in a fuller, more textual way. Together, our dual focus on substance and form comprises the two broad purposes of the self-study: to better understand the relationship between teaching and learning, specifically, as they relate to one's autobiography; and to explore the use of non-conventional forms for understanding and representing teaching and learning. We used verse, music, and dance as organizational and analytical constructs and metaphors to explore and represent the relationship between self as teacher and self as learner.

Living

and Dying with Dignity:

The Alzheimer's Project

Ardra L. Cole and Maura McIntyre

The memory loss that accompanies Alzheimer's is perhaps the most striking feature of the disease. Those stricken with Alzheimer's gradually lose touch with themselves, their loved ones, and their personal and social location. They forget. Those in primary caregiving roles can also experience a kind of memory loss as they get caught up in the immediacy of coping with the practical difficulties associated with caring for someone with Alzheimer's disease. In order to explain the personality changes and unpredictable behaviours that accompany the loss of memory it is often said that the person is gone. Through our mothers both of us have first-hand experience of the devastating effects on individuals and families stricken with Alzheimer's Disease and of what it means to care for persons with the illness. As daughters, caring for our mothers at home and in institutions and witnessing their physical and mental decline, we felt and continue to feel a moral imperative to advocate on their (and others') behalf for the preservation of human dignity within the context of health care. We feel a certain imperative to actively remember our mothers-who they were as healthy, vital women and who they became as women with Alzheimer's. The process of actively remembering our mothers returns to them their dignity and makes explicit their ongoing capacity and continuing role in our lives. In the 'Alzheimer's Project' we use various metaphorical frames to remember and represent elements of our mothers' lives and, more generally, to interrogate the constructs of illness and health as they relate to the presence and preservation of human dignity.

We identify our research as 'advocacy work'; we, therefore, are concerned with issues of research relevance and accessibility. We extend our work beyond the walls of academic institutions and into communities where we hope to provoke and facilitate discussion among care providers (family members and health professionals). To do so, we draw inspiration mainly from tableau and installation artists.

The Alzheimer's Project is comprised of several three-dimensional multimedia representations based on predominant themes emerging from our research. Data informing our work are from multiple sources: personal writing, journal entries, caregiving notes, photographs, personal documents, library and internet research, and a series of structured conversations about our experiences. The six themes represented in the installations, subsumed under the overarching theme of dignity, are: caregiving and contexts of care; dependence; education; mother-daughter relationships; memory; and, identity.

Life Lines

materials: concrete blocks, clothes line wire, aluminum clothes line reels, "s" hooks, nylon rope, clothes pins, clothes pin bag, astro turf, folding lawn chair, sprinkler, fan, overwashed white female undergarments

description: A free standing clothes line about 20 feet in length is held up by ropes and secured by concrete blocks at each end. Astro turf carpeting represents the grass below; a chair invites the viewer to sit and relax. The clothes on the line are blowing in the breeze. The undergarments are ordered from left to right according to the time in the life cycle at which they are worn.

interpretive text: The female undergarments represent a life line of feminine learning. By airing our laundry in public, we are bringing into view what have traditionally been the private spaces of learning between mother and daughter. As our eyes move along the line from baby diaper to lace garter belt to adult diaper we are reminded of the shift in personal power over the most basic and private elements of a woman's life that occurs over a life span. The undergarments move differently in the breeze with varying degrees of liveliness-symbols of the changing nature of dependence along the life line. Our responses to each of the garments on the line, from the adorable baby's undershirt and plastic pants, through to the multi-hooked nylon brassiere and extra-large size plastic pants gives us information about each of these stages in the life cycle as a site of learning. Do we want to take the baby plastic pants off the line and see if they smell like powder? Or slip off with that padded push up bra and see if maybe it might fit? Do we want to take the adult diaper off the line and touch it?

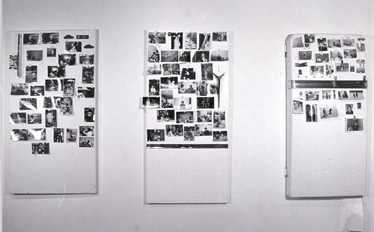

Still Life with Alzheimer's I

(Maura and Eilene)

materials: three fridge fronts, black and white photographs, colour photographs, magnets, wire

description: The fronts from three white fridges backed with wire are hung in "chronological" order on a wall. The first, a "Norge Customatic" circa 1950, has rounded edges and chunky chrome. Affixed to its front with magnets are photos, mostly in black and white. Mother, with horn rimmed glasses and red, red lipstick is young. Daughter is infant, is baby, is girl, is teen. The second fridge, an "Admiral Deluxe" circa 1965, is rectangular and sharp cornered, the chrome handle stream lined and pointy. It is covered with photos, this time in colour. Mother and daughter are both adults. The final fridge, a "Westinghouse" circa 1980 is so plain that it is nondescript. In the photos mother is ill, daughter is older.

In presenting the images Maura felt that she needed to find a way for the medium and the message to intertwine. She realized that she wanted to recapture that feeling of movement, of the everyday, of ordinariness in the mother-daughter relationship over time. And what could be more everyday, more ordinary than a refrigerator? Refrigerator fronts are not for posed family portraits. Fridge photos are not framed and finished but full of movement and vitality. Fridges are where we put snapshots, those fleeting moments caught by the camera. Fridge photos, themselves, are not permanent: they might get wet, stained, or lost. They hold the indelible yet ephemeral images of everyday life.

interpretive text: On the first fridge, Maura's mother is young and vital. She is "getting into the car", she is "working in the kitchen", she is "a young professional". Maura is "baby in the bath", she is "toddler running on the grass", she is "irreverent adolescent sitting on the kitchen table". Together they are "beside the wading pool", they are "at the table eating", they are "walking through the snow". Life.

On the second fridge, Maura's mother is middle aged and vital. She is "travelling in Japan", she is "costumed and outrageous", she is "naked holding grandson". Maura is "travelling to France", she is "on a ladder roofing", she is "sitting naked with son in wading pool". Together it is "Maura's university graduation" and her mother has just hooded her, they are "deep in conversation", they are "laughing together on the couch". They are enjoying being adult women together. Still life.

On the final fridge, Maura's mother is older and ill. She is still "costumed and outrageous", but what we know is that someone has helped to dress her up. It is "her birthday" and Maura's daughter has presented her with her diabetic jello "cake". She is slumped over, "sleeping in the easy chair". Together, they are "in her wheel chair bike" but Maura is driving; she is "being bathed" and Maura is bathing her; "she is eating" and Maura is helping her. Still life with Alzheimer's.

The images on the three fridges represent both the changes in Maura and Eilene as individuals and the changing roles they have assumed in each other's lives. The images also reflect how little they each have changed and the continuity in their relationship. Taken together these images form a narrative of teaching and learning in a mother-daughter relationship, in illness and in health.

Still Life with Alzheimer's II

(Ardra and Marie)

materials: photographic images on foam core; narrative text on paper

description: The photo-narrative depicts, through visual and literary text, how, while relational roles may shift through wellness and illness, the fundamental nature of the mother-daughter connection transcends time, circumstance, and context. Also illuminated is the history that is often forgotten when a vital, active woman becomes just another resident to care for. The photographic images and the narrative texts each tell a separate but interrelated story. They can be read as parallel or corresponding texts.

The visual images, selected from family photograph albums, were chosen because they so clearly signify the mother-daughter connection over a life span and poignantly elucidate the role reversal that inevitably occurs when Alzheimer's interrupts, confuses, and redefines a relationship.

The texts contained within the books are modified excerpts from personal reflections written as part of a larger memoir. The books were created to frame the text because books, like photographs, exhibit a permanency that reminds us that, regardless of human capacity, a life has a history and is a rich text. The selections exemplify the elemental nature of a mother-daughter relationship and how, regardless of location, the depth of that relationship is expressed through attending to the most basic human physical and emotional needs. The stories themselves also prompt us to remember the person inside the fading mind and body of someone with Alzheimer's disease.

interpretive text: One of several narrative threads joining the images is physical connection. The movement from mother holding daughter, to close but independent physical proximity, to daughter holding mother portrays the cyclical and reciprocal nature of relational interdependence. Metaphorically, the holding of daughter and mother signifies a reluctance to let go-of the other, of roles, and of that relationship.

The brief narrative excerpts each tell a human story of relationship. They are presented in small word clusters or meaning units to encourage readers to hold onto and be thoughtful about each word on each page of text-to pause and remember, to engage in the creation of a personal narrative. The ambiguity in the text created by the undefined use of the pronoun "her" highlights the role reversal of mother and daughter in health and illness. It also creates a level of discomfort brought about by the acknowledgement of the close association between independence and human dignity.

Life Cycle

Writing

Life Cycle is comprised of several clusters of objects grouped in sets of three. The theme is education: what we learn from and then try to re-teach our mothers. Each set of objects contains a symbol of childhood, adulthood, and Alzheimer's hood. Two segments of the installation are complete.

Reading

materials: 3 wooden stands, books

description: Each of three books is lying open. The first, baby's first book (made out of hardened cardboard) is colourful, cheerful, and well worn. The second, the doctoral thesis is well kept, plain and serious. The third, a book of poetry, shows signs of disrespect and disrepair. Pages are ripped out, the margins have been written in and words underlined in crayon. Emerging out from between the pages are a packet of denture cleaning tablets, an emery board, and scraps of paper.

interpretive text: Baby is proud of her first book. She has mastered the alphabet. Her sturdy cardboard book is touchable proof of the solidness of her achievement. She likes to carry her book around and show it to people. She recites the alphabet and shows what a good learner she is.

Woman is proud of her thesis. She wrote it and she defended it. This solid hard bound book with her name embossed on the spine is touchable evidence of the solidness of her achievement. She feels proud when she thinks about it sitting on the shelf in the library.

Older woman won't be separated from her book. She likes to carry her book around and show it to people. She writes in it with crayons, with eyeliner, with anything that will make a mark and sometimes rips out the pages and puts them altogether in the toilet. She "reads" passages to show that it is her book.

Life Cycle

Writing

materials: plain black picture frames with glass, childish handwriting sample, child's crayon drawing, postcards, stamped passport pages, sample of Alzheimerhood handwriting attempts

description: Three separate "collages" hang on the wall. Framed in the first is the confident printing of a little girl who knows her name and her place. She has accompanied her written work with a crayon drawing. The second frame holds a series of postcards and passport pages. The cursive writing is clear and fluent. The text indicates that the author is a world traveller who has strong family connections. The final frame holds an enlarged photo copy of an attempt by a woman with Alzheimer's to write name and address.

interpretive text: Girl is proud of her first writing. She prints her name constantly, everywhere, in big block letters. Soon she can write her address too!

Woman loves to write home when she travels. She wants to share everything that she sees, hears, thinks, feels-all the places, all the people. She is constantly excited, she is constantly learning.

Older woman writes her name constantly, everywhere, in small tense handwriting. Soon her last name is too long, too difficult to get all the way through. Soon she can't write her address either.

In each of the Life Cycle installations, the sets

of three objects tell a story of teaching and of learning. Girl is a proud

learner; her reading brave, her writing bold. Woman is confident and independent;

her writing lively, her reading significant. Older woman continues to

seek access to these places of power in her past.

back

to index

the

earthworm

by Nancy Davis Halifax

I wander through the streets, my everyday surrounds, my plain thoughts. Some thoughts are not here yet. Thinking the unthought. The silence of the unthought is not the silence of resistance to an area of being; it is the quiet of the rose in its blossoming. What claim does this mortal creature have upon me? She calls out to me, will not let me walk by and brings me low to the ground. Slow and continuous all earthworms share the same progenitor. My imagination when freed stoops to the ground to pick up leaves, small bodies. The death of an earthworm is real and I know of no way to help her in her suffering. What is it to witness the death of a small creature? Does her death provoke me to avoid thoughts of my death, the death of dark thoughts unearthed? No, she helps me to perceive that I have been made a corpse while still alive. The worm is silent and it is this silence that beckons me. I carry the touch of her body upon my hands and spirit like faint scars. The earth is written by her body. The earth is her text. Drawings are like worms, I think, each enters us in silence, through them we hear silence. The language of worms, the invertebrate text lies at our feet, a dead script. The drawing of a worm repeats slowly, earth moves through this drawing. Follow me: lay your body on the earth beside mine, mime the positions that I was taught during my tenure underground.

This body of work contemplates

our animal vulnerability and has its origins in my immersion in a sensation

that resists translation. It is a sensation that I could have ordinarily

left aside, but the encounter pricks me. Perhaps the sensation chose me

because it is or can be experienced by the artist as s/he works-the experience

of being vulnerable, a bloodied embodiment of writing deep into flesh,

down and under the red of our animal meat.

back to index

Artistry,

Inquiry, and Sense of Place: Secondary School Students Portrayed in Context

by J. Gary Knowles

& Suzanne Thomas

Artistry, Inquiry, and Sense of Place consists of a series of photographic and mixed media assemblages created by secondary school art students who are creatively inspired by the work of internationally renowned 'place' photographer, Marlene Creates, from Newfoundland. This inquiry involves students in an exploration of place and sense of place in school and interweaves the elements of Creates' artistry into life history researching processes (Cole & Knowles, 2001; Creates, 1990, 1991; Knowles & Thomas, 2001, 2002; Thomas & Knowles, 2002).

We see the absence of students' voice in current agendas of educational reform, and believe students hold personal knowledge and perspectives that have the potential to significantly inform future educational directions (Erickson & Schultz, 1992; Pollard, Thiessen & Filer, 1997; Levin, 2000).

We engage students as 'prime collectors' and interpreters of experience and empower them by capturing, exhibiting, and representing youth-generated knowledge, experience, and perspectives of sense of place in schools. They explore the cultural dynamics of student life within the context of school by examining school as a 'sociophysical' environment (Berleant, 1997) and identify the qualities and dimensions of place that are most influential in shaping ways that they approach learning. Inspired by the work of Creates, student photographic assemblages consist of a self-portrait, memory map, photo of place, place narrative, photo of self-in-place, "found artifact' and a two or three-dimensional artwork.

Artistry, Inquiry, and Sense of Place is unique in the extent to which the convention and form of art influences the inquiry 'process' and 'product', as the multi-media exhibits of student photographic assemblages represent simultaneously the elements of a multi-faceted information gathering, meaning-making and knowledge. This research reflects learning from, and responsiveness to, the discipline of art as a way of informing alternative 'data' gathering and representational modes of social science and educational inquiry.

Media: framed photographs, textual narratives, 'found artifacts', two/three dimensional artwork.

Portraits of Land and Sea & Arctic and Tropics

|

|

Arctic/Tropics

Poles Apart and Portraits of Land/Sea represent a series of arts-informed,

collaborative self-studies that draw on the principles of life history

research and reflect the perspectives of experiential knowing and reflexive

inquiry. As inquirers we trace patterns and elements of our place experience,

place memory, sense-of-place, and explore personal history experiences

within natural and institutional contexts. Our intent is to deepen and

enrich our understanding of experiential place perspectives, to acknowledge

their impact on the foundational principles of our teaching, and to broaden

the development of a pedagogical theory that engenders a sense-of-place

in education. We focus on ways 'place perspective' influences our fundamental

pedagogical assumptions and practices while representing our interpretations

and insights through multi-framed, two-dimensional installations. The

complexities of our multi-layered processes of intuiting, sensing, responding

and interpreting are represented through the artistic elements of sailcloth

canvas paintings, natural artifacts as 'found objects' and a series of

mixed media panels and textual frames. The essence of our work requires

a re-visioning of a pedagogical orientation that engenders an awareness

of our deep-rooted connectedness, interdependence and interrelatedness

to others and the natural world. Our explorations of place, experiential

perspectives and pedagogy continue as a work-in-progress as the textual

and multi-framed two-dimensional installations simultaneously become arts-informed

inquiry representation and 'data' for future discourse and theoretical

development of a sense-of-place in education.

back to index

Images

of September 11, 2001

by Lisa Lipsett

Images of September 11, 2001

This installation, comprised of nine images reveals the power of painting

to embrace the complexity of a moment in time. The images range in content

from a screaming woman, a flag, the cosmos, burning and exploding buildings,

and weeping beauty in a harsh black-white reality. Through the alchemical

process of painting, pain and grief can be transformed into strength.

The act of painting roots us firmly in the present moment while being

simultaneously predictive and historical. We are afforded the opportunity

to join the seemingly disparate in a sensuous interplay. Painting stills

life so that the personal dances with the cosmic, the natural interweaves

with the cultural, and the simple is given context by the complex. By

opening to the colour and form of an experience, it can be deeply felt,

completely embodied, at the same time as it is stilled forever, to be

relived at will, each time offering deeper understanding. In this sense

painting is a transformative self-making process, where the experience

of self is melded with an enriched experience of life.

back to index

On

Boxes and Words

by Kathy Mantas

In August of 2000 just before they, Olivia and Amelia (pseudonyms), began this collaboration, Amelia was in London, England to visit family. While wandering around the newly refurbished Tate Modern Gallery, she came across an installation entitled "After the Freud Museum" by artist Susan Hiller. In this exhibit, it was the interplay of word, text and the "unsaid" that excited Amelia.

Hiller's exhibit was comprised of a series of twenty-seven customized cardboard boxes generally used in archaeology to classify and store artifacts. Hiller says of her installation:

…my starting points were artless, worthless artifacts and materials - rubbish, discards, fragments, trivia and reproductions - which seem to carry an aura of memory and to hint at meaning something, something that made me want to work with them and on them. (Hiller, 2000)

Amelia was familiar with the work of artist Joseph Cornell (Cornell boxes) and was now intrigued by Hiller's particular use of archaeological boxes for her art installation. Later that summer, Amelia spoke to Olivia of Hiller's exhibit and suggested they look at using boxes as a form for their own collaborative inquiry. Olivia (whose work contains metaphors and images of cages, gates, prisons, and boxes) was also excited about the use of the 'box' as a form for their collaborative inquiry.

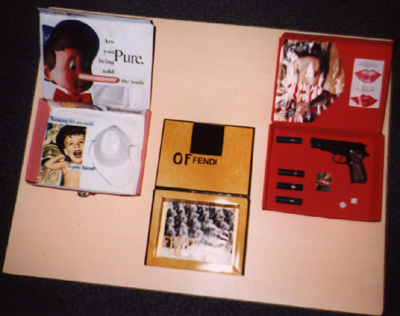

Together they collected various sized boxes. They later discussed the symbolism of colour, painted the boxes and went through some of their personal artifacts (from both their private and public worlds). The chosen artifacts were sorted (several times), grouped thematically, mounted/collaged into the various sized boxes and finally placed on a background made of foam-core. Inspired by Magritte's use of text and juxtaposition of unlikely images, they also searched out words and phrases lifted from magazines and from their own transcripts to go with the contents of their boxes.

Like Hiller's work, arts-based fragments of their own lived experiences are contained in these boxes. The artifacts, the text and their interrelationships can be seen as "epistemological triggers" which evoke their own experiences of womanhood, creativity, teaching, artistry, containment and moments of breakthrough.

Co-researchers

Amelia (pseudonym) has been a teacher for twenty years. She has spent the last ten years working with students deemed "at risk" in the school system. This year she and her students work out of "Portable 5" (the box!). Amelia completed her Ph. D. several years ago. She is interested in arts-based and narrative approaches to teacher self study, as well as the influence of self-directed teacher development on school contexts.

Olivia(pseudonym) has been

a teacher for eleven years. She has taught at both the intermediate and

high school levels. She is a teacher of Visual Arts and second languages.

back to index

Reclaiming the Real: Photographic

Literacy and Historical Memory in Big Intervale, Cape Breton

by Amish Morrel

When my father's father's father had a difficult task to accomplish, he went to a certain place in the forest, lit a fire, and immersed himself in silent prayer. And what had to be done was done. When my father's father was confronted with the same task, he went to the same place in the forest and said; '"We no longer know how to light the fire, but we still know the prayer." And what had to be done was done. Later, he too went into the forest and said: "We no longer know how to light the fire, we no longer know the mysteries of prayer, but we still know the exact place in the forest where it occurred. And that should do." And that did do. But when I was faced with the same task, I stayed home and I said; "We no longer know how to light the fire, we no longer know the prayers. We don't even know the place in the forest. But we do know how to tell the story." From the film Oh, Woe is Me by Jean-Luc Godard (Cinema Parallel, 1995)

These photographs are selected from a much larger collection of images that I either collected or produced as part of my PhD thesis research in the department of Adult Education, Community Development and Counseling Psychology at OISE/UT. They are of Big Intervale, a remote rural community on the upper sections of the Margaree Valley in Nova Scotia where I once lived. According to a petition to the provincial legislature in 1890 requesting the building of a bridge across the river, there were over 200 people living there at the time. There are now fewer than a dozen people living in Big Intervale, and few traces can be found of its earlier inhabitants. In my research, I have been gathering photographs of this area and re-photographing the sites of earlier photographs, the sites that people who have lived there describe to me in their stories, and sites that I remember.

Through this project I am exploring a method for using photography in developing historical memory. In my selection of images, I connect different traces; the photograph as trace of a past event; the traces of human presence that have been left on the landscape; and the traces inscribed in my own memory and in the stories that others have told me. By focusing on the traces held in common between different images, documented history, and memory, my aim is facilitate an encounter with the real, and a deeper understanding of ourselves in relation to the past.

All of the images shown here have been digitized from slides or prints and then output with an inkjet printer.

Holding

Flames

by Eimear O'Neill

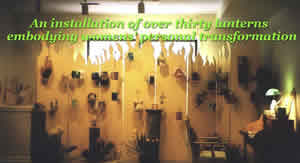

Women self-defined as having

undergone personal transformation were invited to take one of the mass

produced wood lantern boxes available, to capture some immediate sense

of their own journey. Boxes could be used in any way that helped hold

some sense of the particular changes. Artistry was less the issue that

creation of something truly reflective of experience, momentary or lasting.

The only limitations were that the finished piece be less than three cubic

fee and still safely usable as a lantern. The screen, supports, plants,

the curator/ researcher provided digital photo record, guest book and

desk. Lanterns were gathered as the illuminate component of doctoral research

on the processes fostering personal transformation of women's sense of

self. The diverse range of women responding included colleagues, fellow

students and therapy clients, all of whom had undergone some chosen process

of change, whether psychotherapy or less eurocentric approaches such as

work with native elders. A short artist's statement accompanies some lanterns

and some speak for themselves. Confidentially was maintained (i.e., no

names or directly identifying information are on the pieces), though several

participants signed their artist statements and most chose to reveal themselves

to the researcher. The first instalment of the finished lanterns was in

a community accessible gallery space in April 2001, the second at the

Fourth International Transformation Learning Conference. The installation

captures the embodied process and participatory nature of human consciousness

the deep differentiation, subjectivity and communion of each woman's particular

placed experience of change. Lanterns "speak" and "interrogate"

each other, some resonating with familiar themes, many eliciting the viewer's

curiosity. Currently there are thirty-six lanterns, including the researcher's

own work. Together they give some sense of the embodied presence, creative

diversity and many places form which each and all of us, as a community

of knowers, understand transformation. By seeing, responding and filling

in their comments, indeed imagining what their own lanterns might look

like viewers too become participant qualitative researchers.

back to index

Landscapes

of Embodiment and Moments of Re-enactment

by Suzanne Thomas

Landscapes of Embodiment and Moments of Re-enactment, reveals a 'placelessness' in education, human loss of intimacy with the natural world, and a sense of estrangement and detachment from community. It consists of a series of postmodern fragmentations informed by the arts in process, design, and representational form. I draw inspiration from two Newfoundland, site-responsive, landscape artists Marlene Creates and Pam Hall, whose work informs the theoretical and conceptual framework as well as the artistic perspectives, elements, and processes to be applied.

This inquiry focuses on the power of place, the power of biography, and the power of experiential perspectives to inform pedagogical theory and educational practice. It explores place literally and metaphorically as interior - perceived through somatic, affective modes of awareness; as autobiographical - experientially perceived through the exterior environment; and as sensual - perceived through bodily ways of knowing.

Landscapes of Embodiment and Moments of Re-enactment captures moments of 'placeness' that speak to our universal longings to connect, to re-experience community, and to recover a 'topographical intimacy' (Lippard, 1997). It develops a pedagogy of place that engenders an awareness of the nature of our connectedness, interdependence, and interrelatedness - moves us to imagine a 'worldview of attachment' (Lacy, 1995); to engage from a participatory stance rather than an observing one, and to seek place(s) beyond our contemporary, fragmented postmodern geographies.

This inquiry will be represented

through a multi-layering of mixed media comprised of the textual elements

of poetry, narrative, and the visual elements of photography, mapping

and geo graphe drawings.

back to index

Program in Adult Education & Community Development Department of Adult Education & Counselling Psychology Ontario Institute for Studies in Education of the University of Toronto 252 Bloor Street W, Toronto, ON M5S 1V6