Robert Ormsby

Review of Coeur de Chien / Heart of a Dog

In the broad field of Russian literature in the USSR I was the lone literary wolf. I was advised to dye my coat. It was absurd advice. Dye its fur or cut it, a wolf will still not look like a poodle.

Mikhail Bulgakov, in a letter to Joseph Stalin, 1931

Coeur de Chien and Heart of a Dog are two halves of a striking theatrical adaptation of Mikhail Bulgakov's novel. Adapted and translated by Anne Nenarokoff (she shares translation credit for the second title with John Van Burek) and directed by Jean-Stéphane Roy, the productions represent an ambitious and truly collaborative undertaking. Two companies (Théâtre Français de Toronto and Pleiades Theatre) have come together to stage the productions for two separate runs at two different theatres, in two different languages (first in French first at The Berkeley Street Theatre Upstairs, then in English at Artword Theatre's Mainspace).

In some ways the productions take their cue from Bulgakov's own work and career. Although the author may now most often be remembered and revered in North America for The Master and Margarita, he was no stranger to the theatre and theatrical adaptation. Besides a difficult career as a playwright and an association with the Moscow Arts Theatre, he adapted Gogol's Dead Souls and his own novel White Guard for the stage (as Days of the Turbins), the latter earning him both considerable harassment and a lasting place in the canon of twentieth-century Russian drama.

M. Albert — Schwonder

|

The novel Heart of a Dog itself suggests a certain type of adaptation, with its representation of failed experiments in the engineering of human souls. By grafting the criminally alcoholic Klim's pituitary gland onto Sharik's (played in French by Louis-David Morasse and in English by Rafal Sokolowski) canine brain, Professor Preobrazhenskii (played in French by John Gilbert and in English by William Webster) unleashes a struggle between essentialism (whether this means a universalised view of human nature or characterological or biological determinism) and political and cultural difference that unfolds in Bulgakov's satiric prose. The productions take up and dramatise this struggle through their specific narrative alterations, a striking scenography, eclectic acting styles, and in the specific nature of this theatrical collaboration.

Nenarokoff sees Bulgakov's novel, in part, as a fable that is firmly grounded in a universal human experience: ”it is the magic of the fable that attracted me to it and Bulgakov's mastery of presenting the whole world within that little fable. The whole of humanity with its trends and its foibles in just a few characters.“ Roy concurs, remarking “The first note I gave to the designers was that it's a children's fable for adults,” and that “the scientific world of the play is just a pretext to talk of humanity.” Attempting to reflect this quality while maintaining the humour of the novel, Roy sought elements of design that border on the cartoonish: the actors are made up with cadaverous Expressionist visages; when the telephone and doorbell ring, a voice chimes “telephone, telephone” and “doorbell, doorbell” respectively; and the Professor's first entrance is accompanied by sinister silent movie-era organ music (music and sound design by Keith Thomas).

At the same time, Nenarokoff's transformation of the relatively short novel into a one-act, ninety-five minute drama emphasises specifically political concerns. Indeed, political concerns are difficult to avoid, as the adaptation has maintained the broad outline of the story, including the Professor's and Sharikov's (the name he adopts upon becoming a man) dealings with Shvonder and the issues of class this encounter entails. But the adaptation also artfully tightens Bulgakov's narrative focus by eliminating the doorman Fedor, and several members of the apartment building's Housing Committee members, and by folding Preobrazhenskii's maid Maria Petrovna into his assistant Zina (Patricia Marceau). Nenarokoff newly conceived Zina, furthermore, in order to embody what she sees as the Revolution's impact on women's lives in Russian society: “I thought ok, it's their first go at unlimited possibilities and education, they can sleep with whomever they want, leave them, divorce them, it's unheard of.” As a result, Zina is no longer simply the unmarried girl whose modesty makes Sharikov's attempted assault on her chastity all the more horrific. Here, despite her deference to the Professor, Zina (played by Marceau with a confident, sultry elegance) tries to claim her own sexuality; not only is she involved with Bormental' (Eric Goulem), Preobrazhenskii's assistant, she also reserves the right to choose other partners.

Nenarokoff further reworks Zina by having her try to complete her emancipation by fleeing to America, only to be captured and left to a cruel, though unspoken, fate. The character thus not only addresses issues of gender, but comes to embody the political upheaval, human destruction and exodus left in the wake of the Revolution. This dramatised Zina also points to the hopes and risks of transplanting oneself in a new culture, a dilemma that hounded Bulgakov throughout his adult life, and one that reflects the history of Nenarokoff's family, who fled Russia for France shortly after the Revolution.

Both the burdens and the triumphs of transplanted cultures should resonate in a place like Canada, where uprooted peoples have been regarding each other-often in different states of “solitude” — for centuries. Indeed, Van Burek, who is also Artistic Producer of Pleiades Theatre, saw the opportunities and the challenges of carrying out the collaborative adaptation in Canada's two official languages:

I think, culturally and linguistically it's very different [in the two languages] because, as Jean-Stéphane is saying, in French there is a certain rhythm, there's a style, there's a quality, there's a character and personality that comes with the language. As soon as you change from that into English it's not only the language of the performers that is changing, but it is the language of the audience.

He is also conscious of the particular circumstances of his audience in Toronto (a place which enjoys trumpeting its status as the most multicultural city in the world) and conscious of the fact that these circumstances complicate the reception of any universal message residing in the script:

So the reception is also different, and so it may well be that if we were doing this show in French in Montréal or Toulouse there too it would be different. But the fact is that we're doing it in French and in English in Toronto, and I think last night, for me anyway, it was a great treat to see how many Russians showed up. That audience was not there for the French version, so what we're getting now is regular Canadian Anglophones mixed in with lots of Russians, so there too we're getting layers of language, layers of appreciation of the story.

Yet the messages of the script and Roy's powerful scenographic vision borrow from European political and theatrical traditions that French, English and Russian audience members should be familiar with. Indeed, Van Burek sees the production driving home various political points through its design: “so much of the story here is told visually, and that's what bridges cultural gaps. A heavy emphasis on words requires a certain understanding of that language and culture. Something visual just leaps over that kind of a gulf.” Hence, for example, the Expressionist visages noted earlier. Such visual quotation of this tradition is, furthermore, carried over into the blood-red panels of the Professor's apartment walls, and his specimen jars arranged on shelves, in which fleshy morsels (including a hideous human foetus) float in thick crimson fluid (set and costume design by Rudy Braun).

Of course, the red motifs, richly lit by Glenn Davidson, also evoke the “colour” of Soviet Socialism and Stalinist oppression, a connection that Bulgakov himself makes elsewhere (see Professor Persikov's crimson ray in “The Fatal Eggs” for an illuminating comparison). The threat of totalitarian persecution is also discernible in the electric crackling that sounds each time someone speaks on the telephone, whether it is one of the aparatchiks Preobrazhenskii rejuvenates with organ transplants dressing down Shvonder, or the curious hordes of interfering journalists who hound the Professor, demanding to know about his fantastic experiment with Sharikov. The explicitly political comes through strongly in Martin Albert's Shvonder who, in cap and greatcoat, surges about the stage, growling his lines and reading from a sheaf of documents and proclamations (here aptly symbolised by a large ring of passe-partouts) like some socialist realist statue come to life. The production thus cleverly exploits the flexibility of theatrical signs to give substance to or materialise Bulgakov's prosaic depiction of class struggle ruthless co-opted.

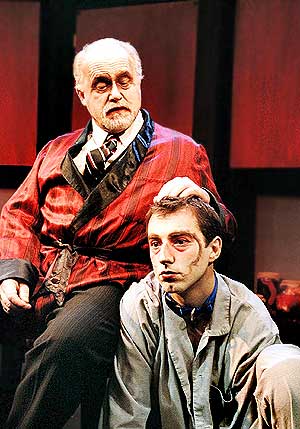

Sitting on a chair Prof. Preobrazhensky (W. Webster), on the floor — Sharik (R. Sokolowski)

Sitting on a chair Prof. Preobrazhensky (W. Webster), on the floor — Sharik (R. Sokolowski)

|

It is this theatrical flexibility that makes Coeur de Chien and Heart of a Dog a pair of the boldest and most sophisticated productions seen onstage in Toronto this year. Roy views the accumulation and counterpoint of theatrical signs as a way to get at what he regards as the multiplicity of meanings inherent in Bulgakov's prose: "There are so many layers in the play, this masterpiece, so my objective was to show a part of the subtext in the staging. I cannot put the whole job on the actors. There are so many layers, they cannot play [all of them] on just one line, it's impossible. So I said let's show them." Thus, for instance, Shvonder's menace is qualified with farce, both in his growling delivery, and in the music that accompanies his entrances and exits, a parodic take on Revolutionary marches.

Frequently, such theatrical layering resides in elements of the set which accumulate both complementary and contradictory meanings. The two operating tables, when pushed together also serve as the dining table (where the Professor tries in vain to civilise Sharikov), and a cage to reign in the misbehaving man-dog. Similarly, the five doors which, along with the red panels, form the rear wall of the apartment setting, serve multiple functions. As part of the wall, they are a relatively realistic means of getting on and off the stage. But when detached by the actors and rolled out into the middle of the set, they acquire a more symbolic purpose. Two are brought out facing each other at angles, with Sharikov and Shvonder behind one and Preobrazhenskii and Bormental' behind the other to represent the stand-off between the two classes. As they open and slam doors, hurling accusations at each other, a sense of danger begins to encroach upon the initial humour of the one-upmanship. Later, after Sharikov has run away, all five doors are arranged in a row from stage left to stage right. With Zina, Bormental' and the Professor slowly opening and walking through the doors, one at a time, looking back in the hopes of seeing Sharikov return, the scene acquires both humour and a touching concern for the creature as the actors slowly draw out the repeated series of motions.

At other times, the multiplicity of meaningful layers is indeed expressed in the acting which mixes stylisation with psychological realism. Although Marceau and Goulem generate a realistically passionate and intense relationship between Zina and Bormental', it is cut across with bizarre gesture and blocking. Early in the play, as the two speak of the transformed dog, sexual tension builds in their voices, although they stare straight ahead into the audience and circle one another sideways, rather than coming face to face. Later, as Bormental' confronts Zina upon her return from a rendezvous with another man, the blocking is initially much more realistic, yet the realism deteriorates into a hilariously frenetic mutual embrace, after which Bormental' is left alone, frozen on the ground in mid-grope.

Features of the acting, are, moreover, brought into focus with the cast changes. Morasse portrays Sharikov far more broadly than does Sokolowski: where the latter plays the role in a physically subdued manner, the former howls like an out of tune Tom Waits as he picks at his balalaika and meticulously embellishes the clumsy, doggish movements of the character. In the same way, Webster's Preobrazhenskii exudes bonhomie, whereas Gilbert's is far more sullen and melancholy. On the one hand, this may have something to do with the direction of Roy, who sees a basic difference between acting in French and English: “in French, I don't know, because of the language, because of the way we are, it was more about comedic timing. But now, in English, it's different, it's more poetry than timing.” On the other hand, this may be a result of the actors themselves: Webster's deep, rich voice lends most of what he does a geniality that Gilbert does not have; and Sokolowski's whole bearing is simply more shy and retiring in comparison with Morasse's shaggy demeanour.

Elements of the design are also driven home with the change in venues. Although both theatres have a flat stage and seats raked at about the same angle, Berkeley Street's Upstairs space, is wider than it is deep, while the Artword Mainspace is deeper and narrower. Thus the sound is allowed to dissipate somewhat in the first space, but seems to shoot up at the audience and takes some getting used to in the second one. The space also effects aspects of the lighting. For instance, when Sharikov swings a bare bulb hanging at chest height on a long wire, the startling effect of the oscillating shadows cast as the bulb sways and as he moves from downstage to upstage of the light are even more sinister on the seemingly narrower Artword stage. This is not to say that either space is more amenable to the design, rather that it is manifested differently in the two theatres.

Doctor Bormental' (E. Goulem) and Zina (P. Marceau).

Doctor Bormental' (E. Goulem) and Zina (P. Marceau).

|

In fact, the change of space bears witness to Roy's ability to adapt the powerful design he has been given to work with. This is made particularly clear in his staging of a song inserted into the adaptation sung in Russian by Shvonder at three points in the performance. Entitled “On the Dusty Road,” it is written from the point of view of a prisoner on his way to Siberia. The refrain runs: “Break my chains release me / I will teach you to love liberty.” Each time he sings it, he becomes more confident, until finally, he uses the song as a kind of weapon against Zina whom he intends to trap.

At Berkeley Street, Roy maintains a certain distance between the audience and Shvonder as he marches, singing, along the floor in front of the stage from left to right. Because of this physical relationship to the audience, Shvonder's appearance remains constant, and the spectacle seems like a detached, though evocative (it is beautifully sung) aesthetic experience, as though we are watching a parade. At Artword, this distance is collapsed. Instead of marching in front of the edge of the stage, Shvonder ascends the centre aisle, pausing under a spotlight three steps up. Here he becomes a very human presence because he is so close and because in the spot, the extremely artificial makeup-indeed every pore on his face-is plainly visible. This living, almost oppressive, presence is particularly felt the third time he climbs the stairs, now in pursuit of Zina who has preceded him. Pausing under the light, intoning his song confidently, Albert still manages to blend his own overbearing proximity with Shvonder's rapacious intent. Again, both are very powerful moments, but adapted artfully for the different physical demands of the two spaces.

Such adaptability points to the great strength of Coeur de Chien and Heart of a Dog. The productions' achievements are in embodiment, in the sense of a transformation from one medium to another, fleshing out and making concrete words on a page. Unlike the disastrous experiment with Sharik, however, the transplanting of Bulgakov's prose here does not result in the same essential creature. Bringing the novel to life, adaptor, translators, director, actors and audiences, have given flesh to the project, bringing with them their own cultural, political and physical interpretations and transformations of the original.

Works Cited

- Bulgakov, Mikhail. Heart of a Dog. Trans. Mirra Ginsberg. New York: Grove, 1987.

- Bulgakov, Mikhail. Letter to Joseph Stalin. 1931. Mikhail Bulgakov and His Times. Trans. Liv Tudge. Moscow: Progress, 1990.

- Bulgakov, Mikhail. “Fatal Eggs”. Diaboliad and Other Stories. Trans. Elendea Proffer. 2nd ed. Ann Arbor: Ardis, 1993.

- Nenarokoff, Anne, Jean-Stéphane Roy and John Van Burek. Interview with Robert Ormsby. March 2003. March 17, 2003. http://drama.ca/drama/main_articles/index. cfm?fuseaction=first&Articles_ID=80

© Robert Ormsby

© David Hawe (photographer)

|