Rachel Perlmeter

Infectious Plasticity:

The Scenic Movement of Andrei Droznin

Of Cartwheels and Cosmic Terror

This boundless ocean of grotesque bodily imagery within time and space extends to all languages, all literatures, and the entire system of gesticulation; in the midst of it the bodily canon of art, belles letters and polite conversation of modern times is a tiny island.

Bakhtin 319

Russian literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin's study of the grotesque and carnivalesque, Rabelais and His World, posits the grotesque body as a cosmic body that is unfinished, becoming, entangled with the world, and decidedly erotic and sensual, as opposed to the individualized, bordered, bourgeois body. For Bakhtin, the individualized (post)modern body has been annihilated by a peculiar desire to smooth its proturberances, conceal its excretions, and deny its vulgarities. His ideas illuminate the oeuvre of Russian theatre director and movement theorist Andrei Droznin, whose project is designed to expose and dispel the physical trauma of contemporary life. Encountering one of Droznin's performances, or observing or participating in his stage movement classes, is a heightened sensual experience. Viewing his creations provokes a bodily confusion: the spectator feels simultaneously within and without the confines of the flesh, provoked to study their corporeal being from a clear objective vantage point, while at the same time, made hyperaware of what it means to dwell inside the skin.

Droznin's most recent creation, Plastic Evening: A Class Concert, at the Schuckin School of the Vakhtangov Theatre, which premiered in the Fall of 2001 in Moscow, is a particularly strong realization of his ideas concerning living movement.[1] Living movement is Droznin's phrase for stage movement that blurs the boundaries between dance, mime, and vernacular gesture. In Plastic Evening, living movement propels its audience into a pliable realm of infectious plasticity that is strikingly fearless. In this realm, inventive physical forms lead the audience to identify viscerally with the performers on a sensual level. The spectator is implicated in choreography that highlights the virtuosic manipulation of everyday objects and dares to present an alternative physical reality.

The sensation of dread is a noticeable component of most theatre and dance construed as postmodern. What is the source of this shifting, often faceless terror? Bakhtin observes that cosmic terror "is the heritage of man's ancient impotence in the presence of nature" (336). In other words, the topography of terror is inscribed in the physical relationship between the human body and its environment. Droznin's scenic choreography re-imagines that relationship, and in doing so, makes use of concepts that Bakhtin associates with folk culture. In Rabelais, Bakhtin traces the rise of the alienated body from the egotism of elite culture originating in Renaissance humanism, to the Romantic construction of the natural realm as menacing and hostile, noting that:

"Folk culture brought the world close to man, gave it a bodily form, and established a link through the bodily life, in contrast to the abstract and spiritual mastery sought by Romanticism. Images of bodily life such as eating, drinking, copulation, defecation, almost entirely lost their regenerating power and were turned into 'vulgarities.'" (39)

The disconnect that Bakhtin describes is both psychological and physical- and is a parallel to the condition that Droznin has diagnosed in the modern theatre. Droznin seeks to invent a new type of movement that might free participants from this crippling fear of the unfinished nature of the human organism. Such a way of moving seeks to release the will from its desire for intellectual mastery of the body.

Droznin challenges the actors he works with to be masters of a rigorous physical technique, however, he also demands an organic quality of human expressiveness. In his directing and teaching, Droznin asks his performers to organize their bodies in space and time, while preserving their ability to move "naturally." He reminds them that the craft of acting requires them to labor to achieve the illusion of natural behavior before an audience on the stage, in an unnatural situation. [2] It is this teasing, stylized, Rabelaisian naturalism that defines Droznin's aesthetic. Performing "naturally" demands the use of mimetic technique to re-present action as it might occur in everyday life. This learned naturalism, confronted with Droznin's intellectual rationale for a return to body-oriented sensuality in the theatre, produces a conflict in the work that is never resolved.

Droznin's conflict can be understood within the lengthy trajectory of theorists concerned with the schism between the modern individual and the natural world. Droznin reads a wide range of body oriented writers, and theorists and is steeped in erotic literature and art. He is in many ways the prototypical Lawrencian artist: committed to casting off squeamish conventions about the body for extremely heady reasons.

One of the pivotal exercises in the second semester of his first year course in stage movement asks the students to summersault over one another: feet are hooked over shoulders, hands grip the upper thigh, and the effect reminds one of the illuminated illustrations of medieval jongleurs contorting their carnivalesque bodies in all sorts of impossible positions. Droznin explains that this most Rabelaisan exercise is crucial, "because I want the actors to understand-- work is not about looking beautiful-- [he mimics a snooty, put-together sophisticated actor] this is crazy movement." [3] The movement is crazy because it demands the performer to abandon decorum, merging with another body to produce a fanciful, grotesquely comic feat. Bakhtin's analysis of somersaulting circus performers elaborates why such feats disconcert:

"The entire logic of the grotesque movements of the body (still to be seen in shows and circus performances) is of a topographical nature. The system of these movements is oriented in relation to the upper and lower stratum; it is a system of flights and descents into the lower depths. Their simplest expression is the primeval phenomenon of popular humor, the cartwheel, which by the continual rotation of the upper and lower parts suggests the rotation of earth and sky." (353)

Droznin's technique and stage direction revel in primeval phenomena such as these, and nowhere is this more evident than in the classroom where such principles are applied to young modern bodies whose bodily prejudices are not fully fixed.

Attracted to all things that are in flux, evolving and becoming, Droznin is currently focused on performance research, pedagogy, and the creation of a laboratory studio dedicated to the rehabilitation of modern bodies. He argues that contemporary life has gradually stripped the body of most of its natural activities, resulting in a fundamental discomfort with physicality. Thus, performance has a therapeutic value in treating the twin maladies of physical and spatial disorientation, or what he terms space-cretinism, an illness that afflicts every aspect of life.

For Droznin, we are cretins because we lack a sensual understanding of what it means to inhabit the body; we live cautiously, moving through the universe with a sense of dread. He observes: "if I ask a student to close their eyes and lift their arm above their head, and I ask them if it is straight above, if they are sure that it's vertical, they don't feel the difference between vertical and horizontal. A man cannot feel his own body- and you cannot speak of any expressiveness without this. With a body that cannot feel." In this sense, Droznin's work shares some of the concerns of movement and behavioral therapists, who seek to ease their patients' physical mobility by identifying and relieving blockages that prevent natural movement.

Plastic Evening derives its strength from the tension between the casual ease of the ensemble and the craft and skill that enables its style. [4] It is representative of Droznin's career, which has been marked by an attention to the science and the art, the ethics and the aesthetics of movement.

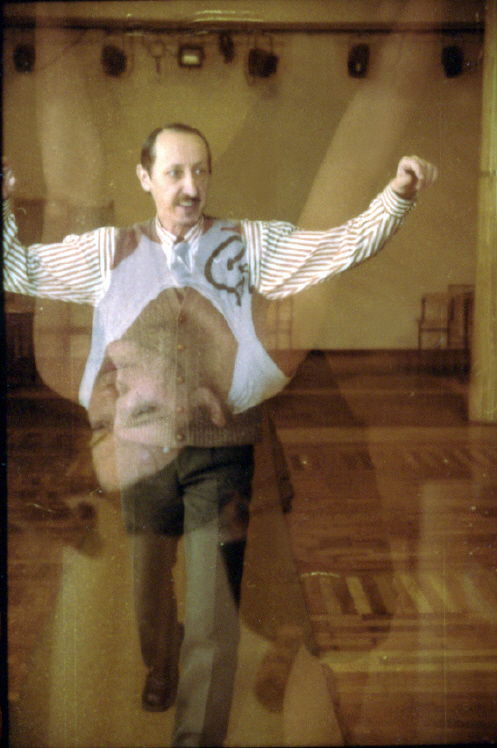

Droznin demonstràting in clàss àt the Schuckin School

Àll photocredits by Fàinà Ostànovà

Droznin came to performance from an engineering background and is still apt to approach scenic choreography with the detailed precision of a draftsman. His grasp of physics may have been the reason he was so impressed as a young student by the work of radical Polish mime artist Henryka Tomaszewski. This highly erotic and athletic mime had little in common with the delicacy of classical white-faced mime artists like Marcel Marceau, rather, his work pulsated with a distinctly current and violently physical sensibility. [5] After seeing Tomaszewski's company perform in Moscow in 1957, Droznin returned to his home city of Orsha, near the Belorussian border, and began researching the art of movement through the study of mime.

Training independently, Droznin became acutely aware of the extent of Russia's lost movement tradition. During most of the Soviet era, materials on Vsevolod Meyerhold's work with Biomechanics were banned, and writings on plastics were scattered and difficult to find. [6] Droznin scoured old theatrical journals and magazines and began a life's work: reconstructing and synthesizing the work of Russia's most innovative directors of stage movement (Meyerhold, Vakhtangov, and Tairov). [7] His technique would later develop as an amalgam of these theorists' ideas, mixed with those of Jerzy Grotowski and Michael Chekhov, and formulated via practice over the course of a rich professional career. [8]

À student in the first yeàr of the scenic movement course àt the Schuckin School

In Plastic Evening, kinesthetic feeling becomes the primary focus of stage action. The production features the graduating class of the Schuckin School in a series of etudes that have little in common thematically other than their living plasticity. In most of the scenes, a solo performer or a pair, working in concert, explore the limits of a tactile object: exploring through movement the widest possible range of its expressions. Droznin notes that "the point is not to move better but to express better… expressivity has many steps… because we are stuck in cages, based in fear, that block us." At times the exhiliration of his actors is so infectious that it is as if windows and doors in the theatre have been thrown open to let a wild breeze blow through.

Ce ci n'est pas une pipe…

In the tradition of Magritte's mocking painting of legend, which proclaimed that the pipe it depicted was not a pipe, nothing abides by definition in Plastic Evening. Objects and bodies defy the properties we typically attach to them and surprise and amuse accordingly. The effect is surrealistic; like Dali's clocks that drip and melt, the objects featured in the performance conform to expectations at the start and then suddenly mutate and evolve into something other than what they are/are not. The viewer is consequently made aware of the irreality of the thing itself and the physical agility of the performer that highlights this quality. [9] However, such prowess proves daunting for the passive modern spectator-for these bodies are rife with ambiguities, moving in unfamiliar ways with reckless gaiety. In Bakhtin's terms, the ambiguities of Droznin's bodies correspond to the blurred boundaries of the grotesque body as represented in folk culture: protruding, moving past its own confines, the grotesque body "swallows the world, and is itself swallowed by the world" (317).

Such an idea of a devouring/devoured body disturbs at first; however, in Bakhtin's analysis the concept actually reflects a joyous, grounded, and fearless relationship between the human organism and its environment. He argues that our contemporary distaste for our "convexities and orifices" misses an essential principle, that "it is within them that the confines between bodies and between the body and the world are overcome: there is an interchange and an interorientation" (317). In other words, we fear a vision of the body that reveals its interconnectedness with other bodies, animals, objects, and the universe at large, when in fact; such a phenomenon has historically been celebrated in the extra-official strata of folk culture. Our legacy as modern bodies is thus not only that of prudish terror, but one of earthy delight at the "interorientation" between our selves and our world. Droznin's performance aesthetic and his movement technique, may startle initially, but eventually they remind the viewer/participant of this basic fearless harmony.

The first image in Plastic Evening is a stage filled with objects: two white wooden chairs, a large blue barrel, a step ladder, a couple of giant inner tubes, some scattered umbrellas, a bunch of reeds, a red hoop, a whiskey bottle and various and sundry other items. What is striking is the latent energy of the objects and a feeling of expectancy connected with their potential use value. The ensemble enters in silence and takes their places in and around these objects. Suddenly- a head pops out from the blue barrel set on its side center stage, and a pounding world music groove begins as the barrel rolls wildly from one side of the stage to the other- scattering the cast in the process. This first etude recalls the feverish intensity of street musicians and steel drum players, for as the performer spins and articulates the barrel, his shaggy haired defiance dares us to keep up with his pace. The barrel transforms from a container, to a ballast- as he balances astride its open end and spins it in a circle- to a pliable surface that he can ripple across. The space inside the barrel seems to grow and contract, becoming liquid around the performer's mutating form. Kissing the audience goodbye before folding in half and sliding down to disappear within the depths of the barrel, the performer's cocky arrogance feels justified. Observing this wild play with orifices, the viewer becomes conscious of the contrasting stillness in the audience. Hurtling into the next scene, the barrel disappears and a long table with two chairs and a pair of domino players takes its place.

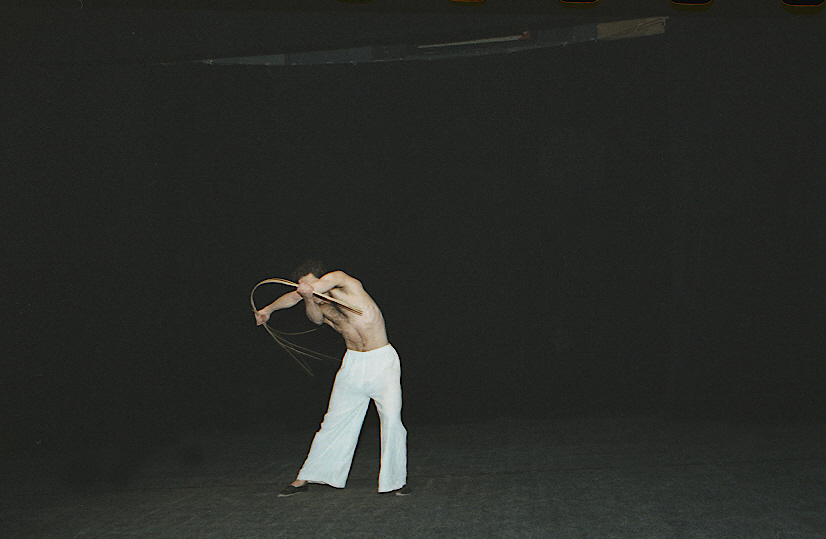

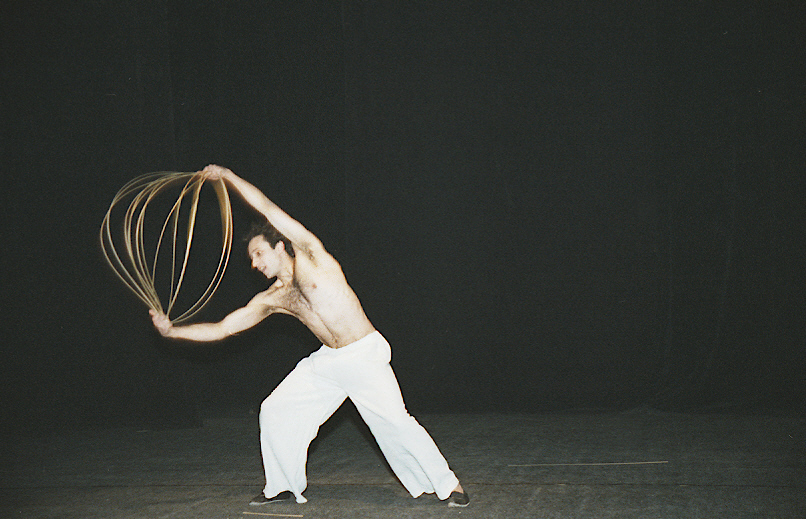

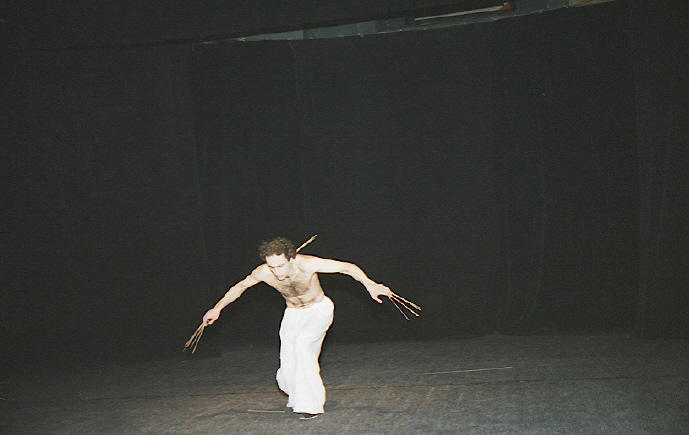

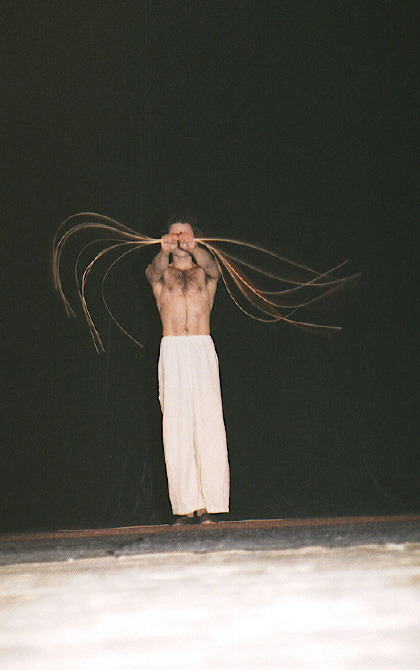

In subsequent scenes the audience is transported from a library to a rain-swept street filled with swirling umbrellas, to an encounter with a fierce performer who kneels on a bare stage grasping two bunches of loose reeds.

V. Bromberg performs with reeds in Plàstic Evening

The reeds trànsform

The reeds become the wing-spàn

Electic reeds

The reeds are extremely stiff and turgid, and the action of bending them requires substantial force. Over the course of the etude the reeds bend and ripple, merge and separate- at one dramatic moment they flicker on either side of the actor's clenched fists like bolts of electricity. Seconds later, spread along the backs of the performer's arms, the reeds create the illusion of the wingspan of a heaving bird. It is difficult to convey the power of a live audience's proximity to such transformations in words or photographs: the pleasure of the crackle that the reeds produce when the actor bends them savagely, or the feeling of a loss when he finally comes to rest with them wrapped around his muscled back. The live spectator shares this effort vicariously; there is a level of endurance required to sit through Plastic Evening as it relentlessly travels across physical extremes in eighteen contiguous scenes.

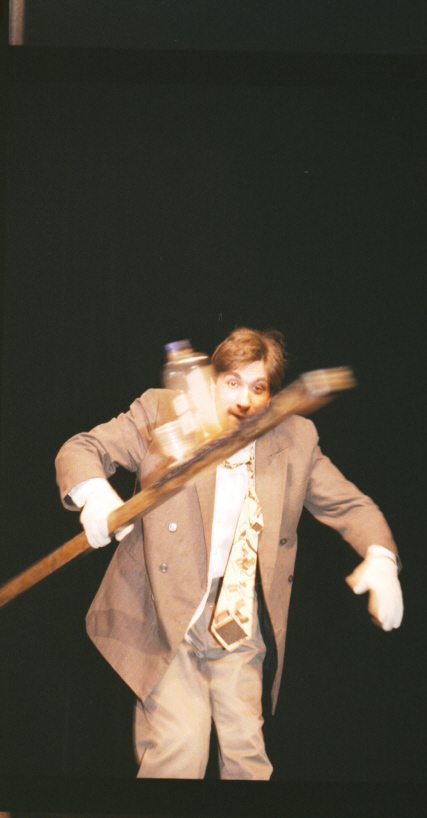

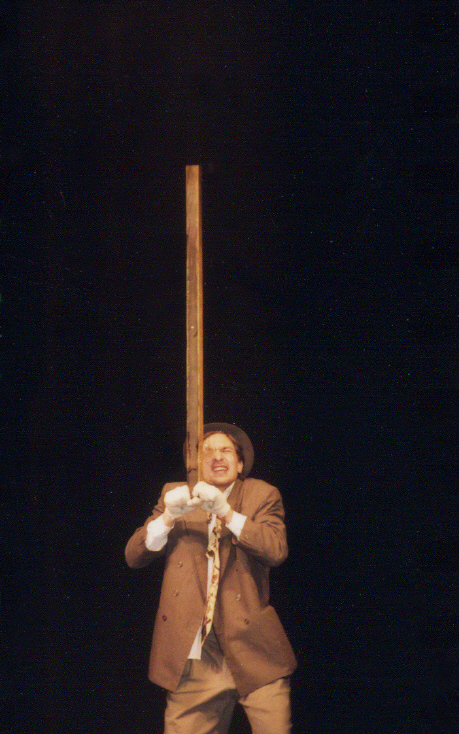

There are moments in many of the scenes that seem to verge on mime; however if the actors achieve the clarity of a mime artist in terms of establishing space and planes that aren't there, they lack the artificiality that the mime's formalized, nonverbal sign system produces. [10] An example of an etude that conveys a complex narrative in this vein features a drunken derelict, swigging to the gritty music of Tom Waits. The action begins with a group of dozing barflies draped along a long wooden plank that they hold, suspended, to represent the bar. The derelict enters, approaches the bar, and whistles several times for a drink before noticing a glass of whiskey and a bottle resting on the plank. The others stumble off and the derelict is left supporting the bar as Waits growls "the first one's always free." Soon the derelict is reeling, spinning the bar and amazingly maintaining the liquid in the glass.

G. Àntipenko mànipulàtes the whiskey bottle on the movàble bàr in Plàstic Evening

Eventually the trick is revealed: the glass and bottle are affixed to the plank via magnets, so they can slide and move and flip upside down. After a couple of shots, the derelict's fantasy life takes over and the plank becomes the long barrel of a gun as he holds it up to his shoulder and "looks through" the glass. Later it will transform into a telephone on a pole, a makeshift coat hook, and the periscope of a submarine.

The bàr becomes the periscope

His fantasy wound down into a drunken reverie, the derelict ends up in the fetal position, wrapped around the bar counter/plank, pulling a last slug from the bottle of Teacher's Special.

Droznin describes the highly narrative capacity of his performers by talking about the foundations of the training system. He explains:

"I'm training future actors and their work is to go to the stage and tell the audience something. For me the communicative ability of the actor is the first quality he or she should possess. Then there is the moral nature- I don't usually talk about this. For something to be in a very bright, sophisticated form, at all stages of forming this future brilliant event, a trace of this special quality should already exist. We want to train an expressive actor to communicate something to another person but already starting at a physical level we must think about how to form the training so that the actor will move towards expressiveness… to find something behind the words, behind the exercises. "

In this way, the deeper emotional life of physicality surfaces in etudes that begin as simple object studies. Movement theorist Moses Feldenkrais speculated that emotional memory lives buried in deep muscle memories; thus, clearing physical blockage frees the psyche as well. Droznin would concur that such rehabilitative work is the only way to get out of the cage, and that strong story telling is its byproduct in the theatre.

Plastic Evening is concerned with the abstract pleasures of shifting spatial relationships over time.

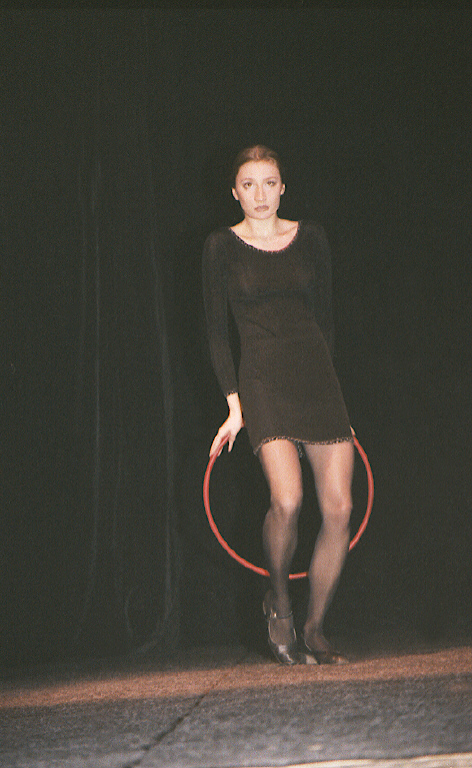

D. Hàbibulinà works with the levitàting red hoop in Plàstic Evening

An etude based on a red hoop that seems to float and levitate and move around an actress' body of its own volition is followed by another scene featuring a red hoop that goes suddenly limp. This flaccid second hoop is revealed to be a red string that, with its ends held together, can imitate its sturdier predecessor. The actor works with the string in a coy way- causing it to smile at the audience and to loop down provocatively towards his crotch. Droznin's understanding of the humor inherent in sensuality, derived from our recognition of its blurry reality, is clearly deployed here. The joke of the sequence is precisely that a string is not a hoop.

Rehabilitating Cretins

If Droznin's formal concerns in performance are to remind the audience of the humor basic to human topography, and to challenge the modern sense of dread that surrounds and cripples the body, his goals in the studio are even more focused on the need to rehabilitate the actor's organism. Organism is an apt term here for the same reasons that Bertrand Russell preferred it when he observed: "the distinction between mind and body is a dubious one. It will be better to speak of an "organism," leaving the division of its activities between the mind and the body undetermined" (821). There is a level on which Droznin leaves so much undetermined, that his own willful, philosophical rationales for this crusade remain unexamined. Instead, the body takes on almost mystical powers: for Droznin, re-socialized, the body can release the modern person from a self-made cage of physical hypocrisy.

It would not be over-dramatizing to say that Droznin views such hypocritical behavior as pathological. In a paper titled "Exile, Extremity, and Animality," Una Chaudhuri theorizes ecopathology as a form of radical exile and alienation from the non-human world. Indeed, what alarms Droznin is just this confluence of mental, physical, and environmental maladies. What might be implied by work that calls for a resurrection of human animality at this historical moment? In Droznin's case, it is a response to the prevailing numbed, mediated, and cynical reactions to cosmic terror.

In opposition to that numbed response that wills the exterior non-human world into an abstraction, Droznin wants to shake his students and his audience by the shoulders and awaken a deep laughter in the face of fear. Such laughter is described by Bakhtin as an ancient coping mechanism:

"It was the victory of laughter over fear that most impressed medieval man. It was not only a victory over mystic terror of God, but also a victory over the awe inspired by the forces of nature and most of all over the oppression and guilt related to all that was consecrated and forbidden ("mana and taboo")." (90)

For an artist who came of age during the Soviet era, like Bakhtin, this kind of un-official laughter represented nothing less than revolution. What drives Droznin then might be a more complicated desire to topple consecrated, calcified approaches to actor training and trigger a liberation movement for the body.

In person, Droznin has the frenzied energy level of a revolutionary. Whether he is in class or in rehearsal or answering questions in his living room, Droznin himself is always in motion. He sits only to spring up again to demonstrate a point or look from a different angle, and he stands at constant attention- ready to rush to an actor or observer at any moment to explain or clarify something (frequently with his hands). The roots of his methods are in trial and error, a willingness to hurl himself into experimentation, and the fact that he truly loves his work.

Asked to describe the evolution of his technique, Droznin begins seated, but soon he is stomping, and eventually recreating the pivotal moment from the first act opening fight scene in Romeo and Juliet, which he staged for director Albert Burov. Droznin explains that Burov wanted the fight to begin slowly and rise to a frenzied temperature, but that he was limited to a small cast:

"Burov said that it should be naturalistic at times, 'but don't make it realistic, it should also be like a dance, but don't make West Side Story out of it… but it should be shocking.' I was walking along the streets and I finally found something. The beginning of the fight was only six movements- [he demonstrates- Capulets- eccentric movement, Montagues- concentric movement [11]- moving in turn- jazzy syncopation] the tempo meant that the audience only saw parts of bodies- it appears that bones are broken. It looks very macabre- with a shock at the end: the Montagues had knives in their sleeves on string that flung down- and the Capulets had knives on their legs. The problem was the rhythm- 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, knife- they couldn't get the rhythm correct and did not have the balance or coordination. Nobody in the theatre at that time ever paid attention to the vistibulata, so I began inventing exercises for this and it became a part of the training system." [12]

In this way, every exercise in Droznin's technique evolved from real needs. Diagnosing various practical problems in the rehearsal room led to the development of a concrete training regimen designed to correct common physical ills.

À gràduàte student demonstràtes how to fàll for the firts yeàr course àt the Schuckin School

Aided by his background in the sciences of physics, engineering, and psychology, Droznin observed that the sense of balance and coordination is broken in contemporary experience. His notorious coordination exercise, developed to attend to this problem, involves moving both arms in 45-degree increments to one rhythm while stepping in place to a different rhythm. It sounds simple, but proves incredibly difficult for most. Mastering the exercise depends on an internal awareness of the two competing rhythms. Droznin disapproves of mirrors in his rehearsal studios because the purpose of the technique is that the actor should sense internally that the exercise is performed correctly. This kind of self-awareness is produced by training the actor's muscle memory.

Droznin observes that many performers lack the ability to retain movement and complains that actors frequently discover an interesting physicality in rehearsal, only to forget how they achieved it the next time. This memory failure in the body is another component of the modern ecopathology. For Droznin, bodies that do not remember may not participate fully in the culture or the environment. The disconnect between psyche and physicality cripples our capacity to engage the world fully and produces unnatural behaviors.

The disconnect is perhaps not best described as a "modern" problem in this case, for here Droznin is adding his voice to a long line of philosophers including Rousseau, Tolstoy, and Schopenhauer, who have urged the bourgeois urban dweller to return to the land in order to rediscover the wisdom found in the laboring bodies of the peasantry. Nevertheless, each of these symptomatic difficulties, brought on by an inert middle-class life-style, must be corrected if movement training is to advance to the next level of the technique where the psychological and expressive qualities of movement become more central to the work.

The visceral power of Droznin's choreography derives from the ways that movement emotes and develops character through action. [13] Every action is understood to be a dual phenomenon, with a psycho component and a physical component, the performer must be skilled in the rendering of both aspects. The training can begin from either an internal or external position, but ultimately a balance must be achieved. Plastic Evening illustrates the results of a process that begins from an external position and gradually reaches the internal, psychological dimension. Droznin begins by sculpting the external elements so that the inner life has a clear form to inhabit. Given the amount of physical handicaps that persist in contemporary actors, the ability to perform expressively is impaired if the limits of the body are not addressed at the onset.

The urgency of Droznin's work, so apparent in Plastic Evening, is a product of his fear that the human race is liable to lull itself into physical extinction. He perceives the situation as a race against time:

"As individuals we realize- I don't move well, I eat too much, I haven't danced for ages, I'm afraid of running, I haven't done that for many years. But nobody now thinks that it's a catastrophe that threatens mankind. And until we realize the gravity and develop the capacity to resolve these problems, nothing will change. We need to reform the schools and the whole system of raising children, because now the only thing that helps is a very naive understanding of health. Jogging along the road with cars or going to the gym- he's training not himself- he's training his muscles, and then I ask such a student to do this [the coordination exercise] and he's helpless. He doesn't understand how it works. It's quite a serious problem. When I first came to the States I'd heard a lot about sports- lots of gyms in America. When I first saw American students I realized that they're worse than Russian students. "

Droznin has charged himself with combating the physical disintegration of human culture.

Droznin àt work

One hopes that his work will prove to have the corrective impact that he desires. Ironically, at the time of this writing, Russian president Vladimir Putin has charged his nation with rediscovering the benefits of physical education and sport in an effort to combat the dismal life expectancy and health statistics since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Perhaps the climate is ripe for Droznin's ideas to take root.

However, for all of Droznin's alarm, it is useful to consider this phenomenon of ecopathological disconnect in perspective. It has been a long time since Western culture has lived with a Rabelaisian certainty of the interdependence of things, and perhaps the natural impulse towards willful mental abstraction is just as crucial a component of our humanness. To strike a balance therefore, might be the best goal for the actor who desires a broadly ranged instrument for depicting the multiplicity of human responses to the ever-present sensation of cosmic dread. Arriving at a balance in today's heady culture presupposes a lot of corrective movement training of the sort that Droznin espouses, and a lot of laughter.

Notes:

Works cited

· Bakhtin, Mihail. Rabelais and His World. Trans. Helene Iswolsky. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984.

· Chaudhuri, Una. Exile, "Extremity and Animality," Theatre and Exile Conference. Graduate Centre for Study of Drama, University of Toronto. 21 March 2002.

· Dorcy, Jean. The Mime, and Essays by Etienne Decroux, Jean-Louis Barrault and Marcel Marceau. New York: Robert Speller & Sons, 1961.

· Droznin, Andrei Borisovich. Personal interview. Moscow, 22 January 2002.

· Hausbrandt, Andrzej. Tomaszewski's Mime Theatre. Warsaw: Interpress, 1975.

· Law, Alma and Mel Gordon. Meyerhold, Eisenstein and Biomechanics: Actor Training in Revolutionary Russia. Jefferson, NC: McFarland& Co., 1996.

· Ìîðîçîâà, Ã.B. Ïëàñòè÷åñêàÿ Êóëüòóðà Àêòåðà. Moscow: GITIS, 1999.

· Russell, Bertrand. A History of Western Philosophy. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1945.

· Ñìåëÿíñêèé Àíàòîëèé. Ïðåäëàãàåìûå Îáñòîÿòåëüñòâà èç Æèçíè Ðóññêîãî Òåàòðà Âòîðîé Ïîëîâèíû ÕÕ Âåêà. Moscow: Artist, Rezhisser, Teatr, 1999.

· Worrall, Nick. Modernism to Realism on the Soviet Stage: Tairov, Vakhtangov, Okhlopkov. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

© R. Perlmeter

|