Meng Li and Richard D. Sylvester

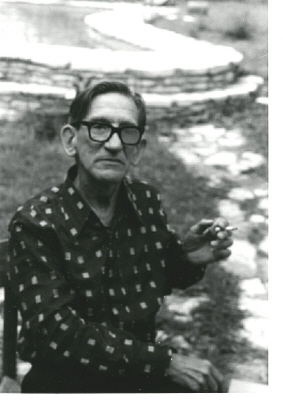

Valerii Pereleshin at the International Poetry Festival in Austin, Texas (April 1974)

Valerii Pereleshin (1913–1992, pseudonym of V. F. Salatko-Petryshche, a Russian émigré poet in China and, after 1952, in Brazil) visited Austin, Texas in April, 1974, as one of the poets invited to the Fourth International Poetry Festival at the University of Texas. He was nominated to participate by his friend the poet Iurii Ivask, and the arrangements for his visit were set in motion by Professor Sidney Monas, Chairman of the Slavic Department at Texas. The nine poets invited were Chinua Achebe (Nigeria), Ai (USA), Ana Blandiana (Romania), Rolf Dieter Brinkmann (German Federal Republic), Russell Edson (USA), Angel González (Spain), Valerii Pereleshin (Russia and Brazil), Nanos Valaoritis (Greece, France, USA), and James Welch (USA).

The poets read their works on the Austin campus on Thursday, Friday, and Saturday April 11-13, 1974. Pereleshin arrived from Rio de Janeiro too late to attend Thursday’s readings, but the poems he read on Friday and Saturday are included in this document in the English translations made for the festival. Pereleshin wrote his own account of the poetry festival in an article entitled “Prazdnik poèzii” published in the New York newspaper Novoe russkoe slovo (The New Russian Word) on 3 May 1974.

While he was in Austin, Pereleshin narrated to Richard D. Sylvester, at the latter’s request, a short account of his life to 1952. Their conversation took place in Russian and lasted four hours. When Sylvester translated his notes into English, he sent them to Pereleshin in Brazil, who returned them with a few corrections and additions.

The present publication is arranged into the following sections:

1. Pereleshin’s Narration of His Life to 1952

2. Commentary to Pereleshin’s Narration

3. Poems Read by Pereleshin at the Poetry Festival, in English Translation

4. Letter of April 4, 1974 from Pereleshin to the U. S. Consul in Rio de Janeiro

Valerii Frantsevich Salatko-Petryshche was born 20 July 1913 (New Style) in Irkutsk.

The Salatko-Petryshche family is Polish Catholic gentry from Byelorussia (province of Vitebsk, district of Lepel’).[1] The family name is mentioned in state archives as early as 1620. In the 17th century many members of the family received privileges from the Polish kings. Valerii has met personally only those members of the family who were his immediate kin. From books (novels and memoirs, especially those relating to the Civil War, 1918-20), it is clear that the family has many branches. One Salatko-Petryshche was a chamberlain (kamerger) who lived in St. Petersburg before the First World War in a style grand enough to give his own balls during the season.

His father, Frants Erazmovich Salatko-Petryshche, was born about 1885[2] and graduated from high school in Vladikavkaz. At the time of Valerii’s birth he was working as a civil engineer on the Baikal section of the Trans-Siberian railroad, then still under construction. He was subsequently posted to Verkhneudinsk,[3] and after that to Chita station, a few versts from the town of Chita; at the former, in 1915, Valerii’s brother Viktor was born.[4] In 1920 the family went to Harbin, the headquarters of the Chinese Eastern Railway that linked up with the Trans-Siberian in Manchuria. In Harbin he worked as a court appraiser; in 1947 he was a professor at the Harbin Polytechnical Institute. He was raised a Catholic but in 1943 he became a Russian Orthodox; it was in that year that Valerii saw him for the last time.[5] He and Valerii’s mother divorced about 1921, and he never remarried. He paid for the university education of his two sons. Valerii says that he felt rather close to his father, who was sympathetic to his poems and quite proud of them. He died about 1955 in Harbin. His parents, Mariia Petrovna and Erazm Frantsevich, were citizens of independent Poland, jovial and good people. They emigrated to Harbin, too. Erazm Frantsevich, an engineer like his son, taught math at the Russian high school in Harbin; in addition to Russian and Polish he knew German and French.

Valerii’s mother, Evgeniia Aleksandrovna Burakova, was born in 1892 and graduated from the gymnasium in Kurgan. In her youth she spoke Polish but later forgot it. Her father’s family was Great Russian, her mother’s father was Polish. Before they went to Harbin, she helped in the building of the new school in Chita and taught Russian there. In Harbin, after her divorce, she married Vasilii Evgrafovich Sentianin, who was head of the Department of Pensions for the railroad. As his wife, she had many social duties until his retirement in 1924. That year the Soviets took over the rights of the old Imperial Railroad Company[6] (as a result of China’s recognition of the USSR in 1924, by which the railroad became a joint Chinese-Soviet enterprise). The family did not become Soviet citizens then. For the children, this meant a change of schools in 1924, from the old railroad school, taken over by the Soviets, to the newly-opened YMCA Russian High School in Harbin, run by Baptist missionaries from the U. S. For Sentianin, this meant retirement, after which the family had to live much more modestly.[7]

After Sentianin’s death in 1927, Valerii’s mother had to work for a living. She translated (from English) for the newspaper Kharbinskoe vremia (The Harbin Times), founded by the Japanese a short time before they took over Manchuria in 1931. Later she went over to the newspaper Zaria (New Day), privately owned by a Russian Jew named Evgenii Samoilovich Kaufman, a very capable and good man loved by all. Her translations were not of major works, but of stories for the Sunday edition; and for a time she edited the women’s page in Zaria.[8] She supported the family.

Valerii graduated from the YMCA High School in Harbin in 1930, magna cum laude. By that time he could read English well and understand spoken English fairly well.

Pereleshin at Austin

He entered Law School in Harbin, graduating in 1935. The faculty of law was organized into sections: economic law, railroad law, and so forth. Valerii entered the “Law Section” (pure law). His most important teacher was Georgii Konstantinovich Gins [Guins], who later taught at Berkeley, where he and Gleb Struve became good friends. In 1935 Gins had Valerii begin studying Chinese in the Oriental Section of the Law School[9] so he could write his thesis on Chinese civil law. But in 1937, the Japanese closed the Law School and several other institutions of higher learning. That year Valerii entered the St. Vladimir Theological Seminary in Harbin..

In 1938 Valerii became a monk at the Virgin of Kazan’ monastery in Harbin (Kazansko-Bogoroditskii Muzhskoi Monastyr’). His monastic name was German.[10]

There were ten to fifteen monks at the monastery, most of whom were hopeless drunkards (“gor’kie p’ianitsy”). They had their own printing press. His memories include a most unpleasant large number of bedbugs. His health suffered: he had a recurrent case of tuberculosis every spring, and finally the doctor ordered him to live at home. Shortly after that, in 1939, he applied for a post with Archbishop Viktor in Peking and got the job.[11] The Archbishop took him in, and he lived in the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission (Rossiiskaia Dukhovnaia Missiia) in Peking until November, 1943. He went back to Harbin twice during that time, to take exams in theology required for his graduate degree.[12]

In those days Peking wasn’t the capital. The Russian colony there consisted of older people who had been notables under the Empire—consuls, ambassadors, and so on. Among those Valerii knew there were the Khorvaths. General Khorvath—Dmitrii Leonidovich—was married to Camilla Benois, the daughter of Albert Benois.[13] She was a vivacious, artistic woman, who liked to put on Russian plays. The Khorvaths lived in the old Austrian Embassy compound, which had been taken over as residences for important families. Iakov Iakovlevich Brandt and his family lived there too: he was a famous Sinologist whom Valerii knew personally. On the embassy grounds there were some separate houses; in one of them lived Valerii’s friends the Popov sisters—five of them. They were all spinsters except the youngest, Mariia, who was married to the son of the last ambassador under the Empire, Ivan Iakovlevich Korostovets.[14]

Valerii was appointed Librarian at the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission. Life there was good. There were a few monks, and many refugees: the Archbishop gave shelter to any Russian in need.[15] Archbishop Viktor was a simple, very good man, extraordinarily charitable. He once took the shirt off his back and gave it to Valerii.

Luckily, three of the priests at the Mission were Chinese, and Valerii took private lessons from them, continuing his study of the language, only more intensively.[16] From them and his other Chinese friends he learned a great deal during those years about Chinese art, theater, literature, and so on. A good many of the poems he wrote in Peking are about China.

Valerii stayed in Peking until “the incident of the armbands” in 1943. By that time the Japanese controlled Peking. Interned nationals hostile to Japan had the right to move freely through the city by day, but they had to wear armbands with the character “Di”, which means “enemy”: these armbands were red. Neutrals and Russians wore green armbands with a different character. After the mysterious death (on 22 December 1942) of Archimandrite Nafanail Porshnev[17] (he was from St. Petersburg, a fine musician and highly intellectual gentleman), Valerii replaced him as Archbishop Viktor’s most trusted subordinate. The Mission had a small dairy of fifteen cows. The Japanese wanted to appropriate it by getting the Mission to agree to sell all its milk to them; then they would process it into dried milk in a plant to be erected in the southern park, which was a part of the Mission grounds. As a lawyer, Valerii knew that the Japanese, once established there, would never leave. Thus he resisted this plan and told the Archbishop why. Among Valerii’s friends in Peking there were several Catholic missionaries, including Italians, Englishmen, and Americans. The latter were, of course, in the “enemy” category. When the Japanese learned of his opposition to the milk plant, they started a rumor that he had loaned his green armband to some of his friends who were enemy aliens. This was a false story used by the Japanese as a pretext to get him out of their way. The Archbishop was forced to transfer Valerii to Shanghai.[18] That was in November, 1943.

Living conditions in Shanghai were awful. In Peking he had been, first, a deacon, then a priest, and he had his own small parish and church there where he conducted services. In Shanghai he had to live at the cathedral (Sobornyi dom), where he conducted services on a “duty roster” system but received no salary. To earn enough money to buy food he commuted twice a week to teach at a school across the river; it was distant and the commuting was arduous. He also taught religion at a Russian school for girls called “Liga russkikh zhenshchin” (the League of Russian Women): the salary was so small that a month’s pay bought a pound of sugar.[19] So on top of all that, in order to make a living wage, he gave private lessons in English and Russian to Chinese.

When he came to Shanghai, Valerii joined a group of poets, all of them Russian, who called themselves “Piatnitsa,” the “Friday” group. They met every Friday at 8 p.m. in a converted garage in Shanghai. Valerii subsequently moved from his lodgings at the cathedral into the garage where the “Piatnitsa” group met. This literary circle was started by Nikolai Vladimirovich Peterets, a Catholic with a Czech passport.[20] Valerii first met him in 1932 in Harbin. When he met him again in 1943 in Shanghai, he was married and lived in a single room, with his wife Iustina [the second poet in the list below], her brother, her mother, and two cats.

Besides Peterets, there were eight Russian poets in the group including Pereleshin:

1. Larissa Nikolaevna Andersen, born in Harbin in 1912 [in Foster, p. 144; other sources give her year of birth as 1910 or 1914]. She was the daughter of a Russian colonel of Swedish origin. She was a beautiful, lively, very capable woman, who published only one book, Po zemnym lugam (On Earth’s Meadows, Shanghai, 1940). In Shanghai she married a Frenchman named Maurice Chaize; they eventually lived in Saigon, Tahiti, and other exotic places, before moving to Yssingeaux, Haute Loire, France.[21]

2. Iustina Vladimirovna Kruzenshtern-Peterets [1903–1983; in Foster, p. 661]. An aristocrat through and through (“dvorianka do mozga kostei”), she published a book of verse Stikhi (Poems, 1946) and a book of short stories Ulybka Psishi (Psyche’s Smile, 1969). She wrote feature articles for the Shanghai newspapers, using the pseudonym, among others, of “Merry Devil”; since then she has been called Mary. As Mary von Krusenstern-Peteretz, she moved to Washington and worked at the Voice of America until her retirement.[22]

3. Lidiia Iulianovna Khaindrova [1910–1986; in Foster, p. 1126]. Valerii knew her from 1932 in Harbin. She was a Georgian beauty (her father was Georgian), black-eyed, black-haired, white-skinned, with fine, dignified aristocratic manners. She was not strong as a versifier, but had the heart of a true poet. She never imitated Akhmatova or anyone else. In China she published three small books of verse: Stupeni (Steps), Na rasput’i (At the Crossroads), and Kryl’ia (Wings).[23] In about 1947 she returned to the Soviet Union. Twenty-three years later, she had some poems published in a provincial journal in Krasnodar. From 1948 until 1968 Valerii and Lidiia were out of touch with each other; then, through an uncle of hers in California, they learned each other’s addresses. After that they corresponded frequently. It was through her that Evgenii Vitkovskii (to whom most of the sonnets in Arièl’ are addressed) first heard about Valerii,[24] and Valerii about him—their whole friendship grew out of that.

4. Varvara Nikolaevna Ievleva [1900–1960; not in Foster] was older than Valerii, and very ambitious. She knew both English and French well—so well that she did simultaneous translating for one of the UN conferences held in Shanghai after the war. As a poet she was cold and correct (“kholodnaia no gramotnaia poètessa”). As a journalist she could be very incisive (“ochen’ ostraia zhurnalistka”): Valerii remembered her story “Tsvety i shtyk” (“Flowers and Bayonet,” on the theme of the chrysanthemum and the sword) about a Japanese general who understood and loved flower arrangement and at the same time tolerated cruelty by his soldiers—and was later condemned by a tribunal. It was probably a true story. In 1948 she returned to the Soviet Union, where she hoped to be given a job as a simultaneous translator. But she was made a teacher of French in a Kazan high school, and soon died,[25] heartbroken. Lidiia Khaindrova later told Valerii that in Kazan one had to walk six versts for water.

5. Maria Pavlovna Korostovets [1899–1974; in Foster, p. 645]. One of the Popov sisters. For Valerii she was his “guardian angel,” though just as poor as the rest of them. She sold stories to Rubezh (Border), a Harbin weekly, and gave the money to Valerii’s mother, just as Valerii gave his mother whatever money he got from his poems. The stories were always very clever. In 1973 when Valerii was in France there was a rumor that she had died. Valerii wrote her obituary and published it in Novoe russkoe slovo. But soon it turned out that she wasn’t dead after all; she was in a suburb of Brisbane, Australia, paralyzed, able to hear, understand, and smile, but unable to speak a word. There is a lot of China in her poems, which are sometimes mystical. They did not think of her as a very important poet, but later Evgenii Vitkovskii wrote Valerii that in Moscow she is considered a very interesting poet.

6. Vladimir Pomerantsev [1914–1985; in Foster, p. 890].[26] About a year younger than Valerii, they knew each other at the YMCA High School in Harbin. He joined the “Churaevka” circle in Harbin.[27] A taciturn and very intelligent man; a follower of Gumilev (“iavnyj uchenik Gumileva”); returned to the USSR around 1947 and no one heard anything more about him. He never published a book of poems. A very nice man, really.

7. Nikolai Aleksandrovich Shchegolev [1910–1975; in Foster, p. 1201]. Born in Harbin in 1910. Returned to USSR in 1947. Valerii met him in 1932 in Harbin. He was chairman of the literary section of the “Churaevka” circle (a group that included all the arts). He was intelligent, an educated musician, who knew English well. He left Harbin when “Churaevka” dissolved and went to Shanghai, where they met again in 1943. He lived in Sverdlovsk, where he taught Russian literature in the local conservatory. He answered a couple of letters from Valerii, but was very cautious; Evgenii Vitkovskii tried to correspond with him, but broke it off because Nikolai answered too cautiously. He never published a book of poems; but he did get something published in the Paris émigré journal Sovremennyia zapiski (Annales contemporaines) which was considered a great honor by the Far Eastern poets, and his poems can be found in Iakor’ (Anchor, an anthology published in Berlin by M. L. Kantor and G. V. Adamovich in 1936). He died in Sverdlovsk on 15 March 1975.

Except for Shchegolev and Khaindrova, who was “one of a kind” (“sama po sebe”), “we were all Acmeists”; or “maybe we all wanted to be Acmeists, and thought we were.” Valerii says only now (1974) is he ceasing to be an Acmeist.

In 1943 when the “Friday” group was organized the conditions in Shanghai were very bad: there was a shortage of food, clothing, shoes, and coal. Someone got the idea of establishing a “game” to be a surrogate for inspiration. Each wrote a theme or subject for a poem on a slip of paper; then the slips were placed in a wine glass and one was drawn. That week, everyone had to submit a poem on that theme. It wasn’t obligatory, but almost everyone would write a poem on the theme of the week. This was a great success. There were twenty themes in all: angels, Gioconda, “through colored glass”, smoke, house, carousel, desert (pustynia), sea, Russia, Dostoevsky, chimera, bell, “we weave lace”, mirror, phoenix, cameo, lamp (svetil’nik), ring, poet, cat (koshka).[28] Valerii wrote a poem on every theme except Dostoevsky.

When the war ended, the “Friday” circle broke up. But to commemorate it they decided to publish an anthology in which all the poems written on the twenty themes could be collected, excluding the failures. Valerii was chosen to be editor, Shchegolev co-editor. They raised money to publish the book by giving two public readings in Shanghai cafes.[29] The book came out in 1946; it was called Ostrov (Island). It was beautifully printed, over 200 pages long, without a single misprint (Valerii did the proof-reading). It is a rare book (Valerii, Larissa Andersen, Mary von Krusenstern, and Gleb Struve had copies). It probably dates 1946, because in 1947 Repatriation began.[30] Valerii called it the best anthology of Russian poetry published in the Far East over the entire period of emigration there.

With Repatriation, the poets began to disperse: four went back to Russia, and four stayed in China. There were two waves of Repatriation, in 1947 and 1948. Those who didn’t return were in a state of agony. After 1948, when the Communists took Shanghai,[31] no one wanted to stay there.

All the Russian papers and journals gradually died out. By 1954 nothing in Russian remained. After 1947, Epokha (Epoch, a journal) published some of Pereleshin’s translations from Chinese poetry; another journal, Segodnia (Today),[32] published some of his own poems, some translations, and an article about a Chinese artist, a Buddhist monk, whom Valerii knew.

Through Shchegolev, who worked for the Soviet paper in Shanghai, Valerii became a translator of Chinese news articles for TASS. He was the best translator from Chinese to Russian in Shanghai. For the first year in this job, he still wore a beard, priest’s robes and cross; Soviet visitors to the TASS office would practically faint when they saw him. In about 1948[33] the Soviets decreed that there were no more Russian emigrants, and all could regain Soviet citizenship. The acting director of TASS talked Valerii into taking a Soviet passport on the last day it was possible.[34] In 1948 Valerii resigned from TASS, because Russian–American relations were very bad, and he eventually hoped to come to the United States. From 1948 to 1950 he did occasional translating for various clients, including, at times, TASS.[35]

Back in 1945 or 1946, a conflict had begun between two of the Russian bishops in China: Viktor in Peking, and John in Shanghai. John was an outspoken monarchist, a supporter of Grand Duke Vladimir, and declared that anyone who did not support this was a heretic. He did not like being subordinate to Archbishop Viktor in Peking. Viktor was a very good Christian and didn’t care much about politics.[36] Late one night (after midnight), John called Valerii to his cell in the cathedral, looked at him in doubt, and asked “What do you think about my becoming an Archbishop?” Valerii replied: “Personally I don’t think anything and I don’t think you should think of it.” From that answer, John understood that Valerii was not on his side in his plan to break away and become an Archbishop. Viktor came to Shanghai on some ecclesiastical business and was immediately arrested by the Chinese police.[37] He was jailed with the pettiest felons for three days and nights (imagine!) until he was released at the insistence of the Soviet embassy. At the time, the Chinese Nationalists were in control of Shanghai. By this time it was clear to Viktor that he had to rely on Soviet support.[38] He agreed to recognize the jurisdiction of the Moscow Patriarch. Bishop John at first agreed to go along, and so did the clergy. Then something happened—not clear what—and John decided to break away from Viktor and assume the title of Archbishop granted by the Synod located in Yugoslavia during the war and in the U. S. after the war ended. Valerii either had to join the rebellious party or remain faithful to Viktor. He declared himself a faithful servant of Viktor, who had ordained him deacon and priest and whom Valerii loved for his noble and generous nature. As a result, Valerii was soon forced to leave the “Liga” school,[39] which had gone along with Bishop John. From that time (1947)[40] Valerii lived in Shanghai and wore Chinese dress.

In Harbin Valerii had written a thesis called “Filosofiia stradaniia” (Philosophy of Suffering). His supervisor was I. I. Kostiuchik. Three of the chapters were published as articles in Khleb nebesnyi (Heavenly Bread), the official organ of the Harbin diocese, including one on Dostoevsky and one on Ibsen.[41] Later, a certain Kirill Iosifovich Zaitsev (no kin to Boris Zaitsev) accused Valerii of an absence of humility befitting a monk for these published excerpts from his dissertation, even though Valerii’s advisor had called it the best piece of work ever done by a student on the theological faculty in Harbin. Zaitsev found an ally in the person of Bishop Demetrius (Nicholas Voznesensky). But Kostiuchik refused to allow this slander to go on, and they were defeated. One day in Shanghai, Valerii happened to run into Zaitsev on the street dressed in his monk’s hood (skuf’ia), with his rosary in his hand and an expression of assumed piety on his face. When he saw Valerii, he bowed. But instead of bowing back to him, Valerii spat, went directly to a barber shop, had his beard and hair cut and emerged as a “layman.”[42]

So from the formal point of view, Valerii is not an unfrocked priest (rasstriga) and has never been officially released from his vows. It is an open question legally. This is one of the persistent inner conflicts in his life, and a source of creative inspiration. This is why King Saul is such an interesting figure to Valerii: one who had been among the elect, and close to God—and then rejected.

In 1950 Valerii tried to enter the U. S. He was detained three months in San Francisco and deported back to the place of origin (i.e., Tianjin; Shanghai was blockaded).[43] His inability to gain entry to the U. S. resulted from his having worked for TASS. For two years more he taught Russian in a Chinese high school in Tianjin [he also mentioned a mining and a music institute]. Finally, in 1952, Valerii’s brother found an agent who arranged visas to Brazil.

For a long time after that, Valerii did not write any poems [though he did begin translating Portuguese poems in 1953]. Around 1955, when he sent some poems to Mikhail Karpovich at Novyi zhurnal (The New Review), Karpovich wrote him: “Vashi stikhi dlia NZh ne podkhodiat” (“your poems don’t suit the New Review”). The Chekhov Press in New York refused his Iuzhnyi dom (Southern Home). In 1967, in the Paris journal Vozrozhdenie (Resurrection) No. 188, a crown of sonnets “Krestnyi put’” (Way of the Cross) was published. This is the first major poem published after his “return to literature” (although a few poems appeared in Novoe russkoe slovo before that). It wasn’t until 1968 that he began to publish again in quantity.

In other autobiographical sources written by the poet after 1974, especially Poèma bez predmeta (Poem Without a Subject, written between January 1972 and March 1976, published partially in 1977-80, and first published in its entirety in 1989), important episodes in his life are discussed in much greater detail than in Sylvester’s interview with him. In one important event in his life, the version in Poèma differs markedly from the story as Valerii told it in 1974. In Sylvester’s notes, Archbishop Viktor transferred him from Peking to Shanghai in 1943 because of false accusations by the Japanese; but in Poèma, declaring he has been silent about it all his life, he blames the evil Russian women he called the “stimfalidy,” [44] who denounced him as a pederast to the Archbishop. In fact, Pereleshin had repeated the first version of his transfer from Peking to Shanghai on several official occasions, but the second version in his Poèma is much more trustworthy, because he did not expect to publish it during his lifetime and thus most likely told the truth in it. The real reason for his transfer can also be found in his letters to his mother and to his old friend Peter Lapiken, who was a gay man but never his partner.

Despite his statement in 1974 regarding his warm relationship with his father, Pereleshin was much closer to his mother all his life.[45] During his stay in Peking (1939-1943) and Shanghai (1943-1950) he wrote letters to her frequently and told her nearly everything that had been happening in his life. In the summer of 1943, after staying at the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in Peking for three and half years, he told her that his position in the church was more stable than ever (letter of 15 June 1943). But in a letter dated 2 September he suddenly said something ambiguous: he was soon going to Shanghai on a mission, yet Peking to him was as dear as a hometown, but he himself had been careless. After he had moved to Shanghai, in another letter, he told her the whole truth and said it was all because of his own insatiability (letter of 9 December 1943). Many years later, in a letter to Lapiken he not only explained the real reason for his transfer, but also connected it with the “evil Russian women,” the “stimfalidy”: he became the target of those who were against him, partly because he was caught during his adventures with boys. After this, the Archbishop could no longer keep him in Peking and had to send him away, but, as he said to Lapiken, the place he was transferred to, Shanghai, a city like Babylon, did not help him curb his appetites.[46]

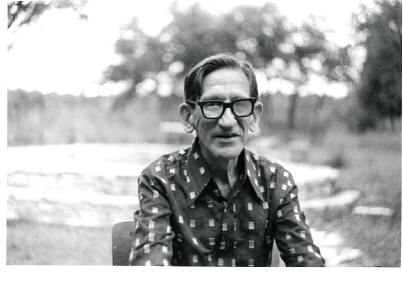

Pereleshin at Austin

Another important event touched upon in Sylvester’s notes is the cause of Pereleshin’s “walking out” of the church in 1946. In his narration Pereleshin emphasizes that he chose the side of Archbishop Viktor instead of Bishop John because the Archbishop was a nice man to him; but he did not explain why he did not remain in the pro-Viktor church, for, during the conflict between the two bishops, four of the eleven clergymen in Shanghai chose the side of Viktor, and in the pro-Viktor Shanghai churches there were twice as many followers as in the pro-John churches.[47] It was in a private letter that he first disclosed the real reason: shortly before his trip to Austin he told Peter Balakshin that “personal temptations also played a part” in the surrender of his monkhood.[48]

The personal temptation in 1946 was a young Chinese man, whom Pereleshin concentrated on in Canto VI of his Poèma and whom he considered one of the two men who ever loved him truly.[49] His name is Liu Xin (1926-1986). They met in the summer of 1946; yet in a letter to his mother in October he claimed that Liu Xin had already occupied such an important position in his life that he felt he could never leave China. In the letter to Lapiken mentioned above Pereleshin explained that his passion for Liu Xin made him feel that he was no longer qualified to serve at the altar, because Liu Xin could come to visit him only on Saturday evenings, and the church service was always the following morning.[50] At that time, Pereleshin had already fallen into a bad relationship with Bishop John and the church. He stopped signing his monastic name “Father German” in his letters to his mother as early as March 1945, moved out of the church residence in the following month, and shortly after expressed the idea of withdrawing from the church in another letter to his mother (4 June 1945). It should be pointed out that Pereleshin’s initial motive for joining the church in 1938 was to “cure” his “illness” of homosexuality, but the move from a soft bed to a hard one did not help him.[51] Since then he had been living in the contradiction between heaven and earth, between spiritual and physical sufferings. His relationship with Liu Xin made this contradiction no longer bearable. It was at that time that the conflict between the two bishops broke out, which offered him an opportunity to get rid of the spiritual burden and to live like a free man. This feeling is clearly expressed in his Poèma (Canto VI: 50). Indeed, in this narrative poem without a subject he was free to include any theme, especially his homosexual love.

Pereleshin did not discuss his homosexuality as a fact of his biography in the interview. He and Sylvester talked in Austin about his conception of what it meant to be “gay,” a condition he expressed as “spiritual lefthandedness” (“dukhovnaia levshizna”), and the forthcoming Arièl’ poems dedicated to “Zhenya” (Vitkovskii): he said to Sylvester in plain words “Ia vlubilsia v nego” (I fell in love with him). It is notable that when he was in China, he was not ready to talk about his homosexuality in print, and his poems of those years never expressed homosexual love in a frank way. But living in Brazil changed him a great deal. Between February 1971 and November 1974 he conducted his intense correspondence with Vitkovskii, which resulted in the love poems for Arièl’. In the meantime, he was writing Poèma and there addressed his homosexuality explicitly and unambiguously. It was then that he visited Austin. In a letter to Ivask shortly after his trip, while discussing a crown of sonnets dedicated to his second true lover, Tang Dongtian (1933-?), in which he described their love indirectly, he admitted: “I would have talked about it straightforwardly now. It is already the Brazilian psychology. The Austinian psychology, too. It simply has come another century.”[52] Then he felt completely free to admit his “duality” in his Poèma (Canto III: 47 – “Da, ia Salatko i Petryshche... to Arièl’, to Kaliban”): these lines immediately follow the stanzas about his visit to Austin in 1974. To a certain extent Austin was a heartening and liberating experience for him. In his own expectation, “after twenty years of isolation in Brazil it will be a bag of oxygen.”[53] Actually, in the early 1970s, his audience was already growing. Ivask had helped him get his poems published and opened doors to critical discussion of them by Aleksis Rannit, Simon Karlinsky, and Dennis Mickiewicz. Now he had an audience which extended beyond Russian readers to poets and others like those he met in Austin. It was there that for the first time he freely admitted the fundamental fact of his life in a public way before an audience of sympathetic and understanding readers. After such an experience he had a feeling of “being in heaven.”[54]

Before coming to Austin, Pereleshin had chosen 34 poems for the poetry festival. Among them were 12 written in China.[55] The significant difference between the poems of his Chinese and Brazilian periods, besides the different ways of treating homosexuality, is, as he stated in a letter dated 1973: “Gumilev ceased to be my only master. Indeed, I have learned in the last five years more new things than in the forty years before that.”[56] It should be pointed out that Gumilev was his master only technically. Spiritually he was never an Acmeist.

3. Poems Read by Valerii Pereleshin at the Fourth International Poetry Festival in April 1974

Pereleshin sent the typed poems in Russian to Austin in advance, and, except for two of them, they were translated into English by Carol Anschuetz and Richard D. Sylvester, faculty members of the Slavic Department of the University of Texas at Austin. The translated poems were typed onto slides for overhead projection during his reading, or read out in translation by Sylvester. The translations, here published for the first time, stand as originally written in 1974, with some revisions made for this publication.

- Day and Night (День и ночь)[57]

1

We are day and night, not just antipodes:

You, flaming, ecstatic, diurnal,

You don’t mind boxing, or the beer-hall,

Or changes in literary fashion.

But I am of the night. The uncounted years

I have filled with watchful silence,

For which alone – how many times –

I have forcibly delayed the dawn!

Is it not in these enchanted hours

That the scales of the universe tremble,

And Phoebus, unwilling, submits to the poet

Ready to help him with a rhyme?

But in the end I give in to the light,

And as before, again we’re day and night.

2

Day looks dressy and handsome,

Plays a concertina, and wears flashy rings,

But every polished diamond there

Shows the heart of a boastful man.

But then – the night, falling over the gulf,

Squints with ten thousand eyes,[58]

And starts to scan her story out,

And, like her, I become clairvoyant.

Through thin, draughty darkness

I launch a swift dream

Into a world of sails, papyri, and decay.

All restraint gone, I would myself fly with her,

But on the window-pane I hear the rude tapping

Of a tasteless assortment of rings.

-

By the Sea (У моря)[59]

Today at dawn I finished a garland of sonnets

And gave what I’d written the simple name “The Link”:

Am I not also an unseen link in a chain,

Ardently in love with a distant ring?

.

I watch from the cliff. Is that a garnet bracelet[60]

Flashing in the breakers loud with spray, –

Or just a chip of wood? Then pick it up, and roll it out,

Playful sea, to tease the blue sharks!

3. The King (Король)[61]

I saw the King of Norway:

He passed by beneath a red and blue flag –

Like us, but with the obvious advantage

That everywhere he put his foot the land was his.

Here the hills and fields are alien,

But he traversed these too with a proud step,

Though no Arctic sagas resounded

To cheer this great-grandson of heroes.

In Managua, in Monrovia, in Paris

The laws the monarch keeps are his own laws:

Even in Lima the northern ice is with him.

In just this way then, into Moscow’s sad world,

You take with you your other-worldly life –

Transtemporal, extraterritorial!

-

Three Homelands (Три родины)[62]

I was born by the swift-watered

Indomitable Angara,

In July, not a cold month,

But I didn't commit the heat to memory.

.

Not long did Baikal’s daughter

Frisk with me as with a pup:

She gave me some rough caresses,

Then tossed me away with a kick.

.

And I, insensible to changes in longitude,

But alert to every vivid new thing,

Fell into the land of silks and tea,

And lotuses and fans.

.

Captivated by that monosyllabic speech

(Is that not how the angels speak in paradise?)

I loved with an uncomplicated love

My second homeland.[63]

.

Fate is a simple thing, it seems:

One day bliss, the next day woe,

And I was driven out of China

As out of Russia – forever.

.

Again in exile, again in ruin,

I give the remainder of my days

To the province of Brazil,[64]

My last homeland.

.

The air is heavy here, almost corporeal,

And rising in it, in a sorcerer’s spell,

These fragments of old songs will die out,

Signifying nothing.

-

Ars Longa[65]

You squeamishly at once withdraw your hand

On touching mouldy paper which encages

The bookworm in his home among the pages

Of tomes so ceremonious and grand.

Then phantom-like the thoughts before you stand:

That as you dig into the musty ages

Your life will pass, while words of ancient sages

You try (perhaps in vain?) to comprehend.

In pensive mood you sit. The worm now feeling

Safe once again resumes its former toil,

And hurries on more precious books to spoil.

Confess, O Bookworm, if to Fate appealing

You could your life to hundred years extend,

Still would it be enough to gain your end?

-

China (Китай)[66]

That sky, like a blue monstrance,

That overshadows a lost paradise!

That dear yellow sea,

Golden and hungry China!

I love these mottled walls,

These courtyards, pines and flowers.[67]

Ah, not everything is doomed to betrayal,

You, heart, at least, remain true.

Wise heart, wherever life leads me,

You will cherish as a sacred memory

The gentle faces of these girls,

The mild speech of these boys.

And the lakes, dear kindred lakes,[68]

To you, as to a mother’s breast,

I, vassal of misfortune and disgrace,[69]

Used to come to draw quietude.

Like a home after long wanderings,

In this wondrous and noisy paradise,

After several incarnations,

I recognize you, my China!

-

At the Full Moon (В полнолуние)[70]

In the joyous nights of full moons

I’m restless and happy and new:

They are blue nights of witchcraft,

Of sorcery and prophetic dreams.

O Luna, delirious Naiad,

Who fled up to that height,

Of all the flock of luminaries,

I love only you.

I honor Mercury and Saturn,

And am a prisoner to Venus,

But you alone are like an ancient urn,

Inscribed with the noble riddle of sacred characters.

Like heavy sea waves,

The tide rises in me,

And, full of senseless rapture,

I would gladly turn lunatic.

We look, and do not breathe for fear,

In order not to startle it on high:

How nimbly along the slopes and roofs

It finds its mysterious way!

Lull me to sleep, and give me wings,

Make me light, a rival to the birds,

So I'd rise higher and nearer,

Touching not so much as a tile.

So a dear frightened voice

Would wake the indifferent firmament,

And bring me, lover of lunar mists,

A radiant death!

-

Le Mal Invincible[71]

White and shapely was my hand,

Sinner’s hands are always fair,

But from afar I heard Your word:

“Be not indolent, languorous and faint-hearted!”

You Yourself told Your followers

Of the fate of the eye, beguiled by appearances:

“Fearlessly pluck it out and cast it to the dogs,

With the hand that delayed to perform God’s command.”

I believe that Your word abides forever:

My hand, God, tempted me from childhood,

And my hand, unflinching, with a sword I severed,

To search for Your legacy with a free heart.

I’m a piteous cripple, but now I’m pure and plain,

And I see lights more fiery than the sun of day:

Free, I have burned the last bridge behind me,

And I orbit the eternal Sun, like Your planets.

But often since the time when You came to me,

And with a tired quiet voice You called to me,

A fine and light hand I follow in my sleep,

And it steals with a dagger towards my tender neck.

“Fearlessly pluck out that eye…” But how, tell me,

How to kill that captivating and evil dream,

To blush anew like the morning dawn,

How, God, to pluck out the eye of night?

-

Hu Ch’in (Хуцинь)[72]

To hoard up sad weariness

I go out into the deep blue night,

And I catch the distant sound

Of the artless and inconsolable hu ch’in.

A simple wooden fiddle

And its barbaric bow, …

But this is an almost welcome pain,

A whistle of departure and steam.

And more: the sadness of early autumn,

Crickets and chrysanthemum petals,

Falling leaves, and, in the bluish haze,

The lilac crest of a hill.

Who is that far-away musician,

Bending the hu ch’in to his rounded shoulder

With a fragile and a swarthy hand,

Who touches his fiddle, and touches me?

So the light heart changes,

I drink my fill of invisible tears

And with my Muse, a grateful captive,

I will share a stranger's sorrow.

-

Christmas Eve (Сочельник)[73]

Thus causes and effects are subject to immutable law;

I have lost my native land, what is the Nativity to me?

But somehow on the eve, as once in childhood,

My heart leaps, and I await – I know not what.

I had thought, indifferent and exhausted,

I would cripple my life, knowingly crush it with my own hand.

But it turned out differently: bundles and whistles and stations,

A life, like others’, small, harmless and quiet.

If I returned again to the land of protracted night,

Where now, before the birth of the short day,

It may be that your far-seeing eyes gaze

At a photograph but see the living me!

I would approach and say to you fondly, “Mama,

Do you want to share my pre-dawn dullness,

Or, if you like, I’ll lull your heart,

Scanning obscurely Mandelshtam’s Tristia.”

Many a night gray anguish hinders your sleep

And you rehearse your grief day and night, saying,

“How could I not have answered, not gone to the doorstep,

How could I have lost touch with my self?”

I would approach and say to you … The night will hear nothing,

The night has turned gray, grown old, and soon it will die.

Then who will hear? Outside the windows the wind ruffles

The evergreen branches and the branches sway.

-

The South Wind (Южный ветер)[74]

Today the wind is blowing from the south,

And spring is beginning,

And you, my swarthy girlfriend,

Are untrue to me today.

With fixed gaze

You look beyond this place

At a hamlet behind the hills,

Where the apricots are already in blossom.

And further, by the broad river bend

Where you caught turtles,

Carefully nurtured rice shoots

Shine in the morning sunlight.

You see a carefree youth,

Glad of the caressing warmth,

Stepping outside, taking off

His long and much-patched coat.

Your betrothed from the cradle,

He strides boldly along the path between the fields,

And his cheeks are slightly flushed

By the sun which is already hot.

He sings a song, and the notes

Have such a fatal power over you

That, despite your separation from him,

You hearken to his song with all your heart.

But I am far from reproaching you!

O, how could you be blamed

If neither caresses nor a hospitable house

Can take the place of your native land?

So let's throw back the curtains

And let the wind, sent by fate,

The howling wind, angry and sharp,

Blow freely over you!

-

The Inevitable (Неизбежное) [75]

Like some strange blessing that descends upon us,

Our kiss is full of fire and passion swift.

And yet I know: a future time is coming

When I will have to choose your wedding gift.[76]

So let it be: some shaken thrones will tumble,

And mighty cities fall, and forests burn.

Laws that are ironclad were once established,

Once and for all they will remain stern.

I’ve long outgrown all manner of partitions,

Of language, and of blood, and even race,[77]

And all those other age-old walls and fences

With which a man surrounds his private place.

Even today, I hate that coming hour

When, speaking softly, you will say: “My dear,

A temporary harbor may be lovely,

But now it’s time that ship should homeward steer.

My destiny is clear, – you will explain, –

I’m but a door where generations stand

Yet to be born, of small and slant-eyed people

With yellow skin – the color of my land.”

And you will leave forever, disappearing

Behind blank walls which I deny in vain,

– In cold betrayal, though without betraying, –

Into the cruel truth of your domain.

No races, castes, or creeds… Wide as the sea,

Like that same sea, I will remain alone,

Wearily mirror someone else’s dawns,

And, longing for the East: complain and groan.

Alone and free… But truly, what of that:

I’m quite prepared, forsaking all desires,

An unknown passerby, to be the last

To warm my hands at other people’s fires.

-

Three Little Girls in the Neighborhood (Девочки-соседки)[78]

By the sea the morning is chilly.

Gathered on the steps

are a white, a black and a chocolate girl,

three races – one face.

Chocolate, black and white,

and all have a fresh, pure,

blooming and modest

human beauty.

By noon the pernicious heat

will disperse them. They will leave the steps,

chocolate, white and black –

three identical hearts.

-

From Mount Nebo (С горы Нево)[79]

Leave me alone, companion of my travels,

Before the ridge of clouds obscures the setting sun:

For the last time I gaze from Mount Nebo

Upon the beauty of the promised land.

We chose not the rights of bondsmen but of sons,

And for forty years, through a lifeless desert,

We wandered to this place, and fed on manna,

Sent down to us by God himself.

The sacred boundaries draw me to them,

The windmills, the towers and embrasures,

But, by God’s command, I must

Remain here. Forever alien to an earthly paradise,

I die a homeless vagabond,

But when I am immortal, here I will come home.

-

The Two of Us (Двое)[80]

In one of our incarnations

You must have been my Siamese twin:

You called me then not mentor or father:

Eugene was brother to Valerii.

Our trust was greater then, and our humility,

And we were joined, not by a chain or ring,

But by our mutual beginning and end;

We shared our pain, and the happiness of dreams.

And now I see you in your prime

Across the seas and thirty-odd years,[81]

And I’m not whole, but only half.

But to bring back our lesser kinship,

I would like to caress you as a son –

As you caress your own son.

-

Judgment (Суд)[82]

History will end in Judgment:

Rising out of dusky Sheol

The ruthless monk Savonarola

Will judge Paris, Pompeii and Sodom.

Then we too, brought low by our shame,

Will pay our debts to the last cent,

Burdening the Lord’s throne

With all our yearning, love and labor.

Then all will be ignited, to smoulder on forever,

Basilicas, palaces, libraries –

Gratuities left to the querulous fire.

How then shall we answer

For the music, for the impassioned sonnets?

Your verses even I will not be able to preserve!

-

Heaven on Earth (Земное в небесном)[83]

For Yury Ivask

Like a nurse to man in his childhood,

in that first Biblical dawn,

well before Melchizedek,

heaven was a guest on earth.

In striped pavilions,

recognizing their visitors by a secret sign,

people shared their meat and drink

with hungry winged angels,

they too broke the round loaves,

promising heaven’s favors in abundance.

And afterwards, the earth, in jest,

destroyed the bastions of heaven,

and explained to the apprentices[84]

that the tempter’s face was scarred,

that the ragged cloak of Michael

was patched with something blue;

that this bold pastiche of styles

was evil intermixed with good,

that into cups of pure white lilies

corruption crept like adders;

that swords and armor turn to rust,

that moths eat holes in the brocade…

Earth, take back all your patchwork:

I want heaven as it was!

-

The Castaway (Изгой)[85]

Exile, vagabond, alien,

I have tramped along the ditches and the rails,

But with loyal faith, in my own small way,

And with Pushkin, whom I read in secret.[86]

Russia, keep your spring pure,

Unsullied by this unexampled flood,

And rustle in my ear – despite these mardi-gras –

Your faraway forbidden whisper.

China is love, Brazil is freedom,[87]

But never did I see the spring ice break and move,

And no nightingale has ever sung in my garden.

I have food and shelter. But still I cannot wish

To take the honeysuckle, rowan tree, and goosefoot,

And paste on them their Latin names!

-

The Drinking Starts (В начале запоя)[88]

I brawl or get drunk –

an outcast’s habits:

I wander over the globe

when the drinking starts.

O Brazil, give me back

the right I had at birth

to run effortlessly

upward and eastward!

There the ground is icy,

and Christmas leaves a bitter taste,

and in the sky – the Great Bear

shepherds her cubs.

-

Quarantine (Карантин)[89]

Here there's half-light; in this semi-darkness

Even the free sun is blocked out.

I'm grateful to God my keeper

For this compound gift: good health and prison.

I want to live: I will not accept freedom,

I'll return to the damp straw;

From a distance, envying the breach,

I will not escape to wind and pestilence.

From terror and from early immolation

I will guard imagination’s carpets,

Those poems as yet unborn.

If then from time to time routine oppresses,

Still I am not prepared to run away,

Across the palisade of prayers and quarantine!

-

Two Conjunctions (Два союза)[90]

When they used to say to me in childhood,

In those days when successes were big:

“Here, pick the one you like: either

The merry top, or the ball.

Which one strikes your fancy?”

I – O blest simplicity! –

Would smile at that whole enterprise,

And answer: “This one, and that one too.”

When I was a youth they offered me

The free choice: gain for yourself

This day’s happiness – or

Win honor in your studies.

With inexperience you’re in the dark,

But without happiness life is nothing,

And when I’d thought it over, I answered

As I had before: “This one, and that one too.”

In those hours when the soul was divided

More than once did I repeat:

“Choose the moment of joy at the cost of hell,

Or at the cost of grief take paradise.”

But paradise and the joys of earth

Equally entice when hunger is great,

And that is why I repudiated or

In the name of joyous and.

-

In the Year 2040 (В 2040-ом году)[91]

In the year two thousand and forty

(Excuse an error of some three or four years)

In my country freedom will begin to gleam,

And I, unearthed, will arrive there at last.

Until that time in your Russian blood alone

I'll be hidden. Fashion will not touch me,

And I’ll be spared all changes in the journalistic weather:

For the dead live out of sight and out of mind.

Your grandson then will put into the Preface

Chita, Harbin, school, inconstant health,

My friends, – and you, his granddad.

Repudiated, but consoled in advance,

I foresee the coming celebration:

The Moscow volume: “Valerii Pereleshin”.

-

“Under hats – from the light…” (Под шляпы – от света...)[92]

Under hats – from the light,

Into pillows – from the noise,

From the wind and the night –

We pull up our collars.

We depart as to Lethe,

Gloomy and brooding,

We clown and we mumble,

And write poems.

-

The Lake of Love (Озеро любви)[93]

Ancient lake, hidden in a mountain cleft,

There is no hero who could reach you!

But when I was chosen, your depths cast a spell

Sweeter than all the shallow lakes of earth.

More trusting every time I come there,

I surrender more and more to your ensnaring charm.

Languorous I whisper, as if dreaming: slake my thirst, exhaust me!

And you respond: drown, drown!

It is pure wonder that you answer so tenderly and quickly,

But I am fearful that you crave so much; your secret is still dark,

You, who are so unlike our lakes:

Only he who reaches bottom does not drown!

-

A Day out of the Ordinary (Необычайный день)[94]

It’s a quite extraordinary day:

Where the sea was there are snowy fields,

And above them like a confession

The crane’s cry rises in the blue.

Not this cement but wooden railings

Like those I knew in Irkutsk or Irbit,[95]

And Russia, with the voice of a Brazilian,

Says “Good day” in Russian.

Does a rebel need to breathe

The air of Europe or America,

If even the shy snowdrop

Gaily braves a snowbank?

Heartache unappeased,

Will the ungrateful outcast curse?

… An impossible, intercalary day,

I call the thirtieth of February.

-

Spring (Весна)[96]

The ancient sorcery

Hums again in my blood;

All words are melodious,

Like words of love.

The wind smells of a tender

Southern spring,

Of a joy that is late,

Mad and free.

Such unheard-of joy

Is too heavy to bear,

The young cannot lift

Their weak wings!

Only the heart weeps,

And the night brings no sleep,

Because outside the window

Spring is lurking.

-

A Ballad about Poetry (Баллада о стихах)[97]

I took to writing for the papers

Verse and prose of every kind,

And the going price of my conceits

Was reckoned to be modest.

When athletes got into a brawl,

Or a petty tyrant got caught,

I could put it all down in couplets,

Giving myself away.

Tired of gossip and government hacks,

I fell in love with other worlds,

Aiming to find in higher spheres

Answers unexpected and unknown.

Every verse became transformed,

Lit up as by a comet’s rays.

Vows are easy to make in verse,

Giving yourself away.

Instead of guests, I expected tidings,

Not relay-races but true flight.

Confirmed as a bachelor could ever be

I did not want to soil my cuffs.

I reach for unearthly omens now

From hands dispensing blessings,

But I'm tired of writing sonnets,

And of giving myself away.

Then help me, poets, help me all,

Before my voice falls silent,

To sing in ballads praise of Lethe,

Giving myself away!

-

Peking (Пекин)[98]

I’m flying in my chariot

a yard or two above the earth,

dressed – not in brocade,

but in home-spun Chinese silk.

Once again I have come to Nanchidza,[99]

is it a street or a forest?

So many elms overhead –

forming an impenetrable canopy!

Night, spring. Earth’s warmth.

This street, as the Chinese poet said, is “straight as a hair”.[100]

A stanza of verse comes singing forth

in finished version.

You, exile, returning from afar,

don’t crush your homespun silk.

Remember, you have but one pair of wings,

for the countless ages.

Here at Pei-Kwan,[101] nocturnal pilgrim,

bring your dream chariot to a stop:

the light you see is shining from a window

that once was yours.

-

The First or the Thirteenth? (Первое или тринадцатое?)[102]

Not listening to cowardly voices,

Not mourning the loss of her crown,

Isabella, Princess of Brazil,

Set the slaves free.

But in Russia a crafty orator[103]

Confounded minds with promises of change,

Enlisting for his vindictive business

Traitors, plunderers and thieves.

Not for mercy or a soft heart

Is the country famous,

But forced labor, the knout, the cry of pain.

But I, accepting a Brazilian’s lot,

Celebrate the sacred day of free labor

Not May the First, but May Thirteenth!

-

“Whoever said in his infinite wisdom…” (Кто сказал – от большого ума -...)[104]

Whoever said in his infinite wisdom

that a prison is always cramped,

that a town, or Moscow, can’t be a prison,

that a prison’s not a county, or a country?

Whoever said the planet’s not a home,

another continent’s a foreign country,

or that the Portuguese language can never

begin to sound like one’s own native tongue?

-

The Temptation (Искушение хлебом)[105]

To care so much about eternity, glory

And the soul is absurd:

Isn’t it better, straining and sweating,

To save rubles, and count kopecks?

So Hail to the Eternal Clichés,

There they are: The Prodigal Son and the rich man’s Swine

And there’s winter, who growing fierce, mocks bitingly

At the fabled dragon-fly and at heaven in a cozy cottage.

What about the lilies of Sharon and the birds?

Nowhere is there unsown wheat,

And yet: I still remember, “Our Father”,

Our daily bread, promised by a generous heaven,

And forgetting the temptation in the desert,

I choose a cottage, as I have done before.

-

Children on the Seashore (Дети на взморье)[106]

At the sea’s edge children are building

castles in the sand:

these towers, bridges, and towns

show the work of skilled hands.

On the land their fathers and grandfathers

feel the same delight:

They’ve erected triumphs in concrete

in Messina, Moscow and New York.

But if by an enormous wave

their structures are washed away,

in some atomic slaughter,

both fathers and sons will die.

Yet the children are at work again,

and the sea is creeping up,

and who will utter the last word

at the sea’s edge?

-

The Meaning of History (Смысл истории)[107]

Before the meticulous account of earth’s ages began,

Two friendly and voluble wills

Began a game and took roles:

I am a benevolent minor god, and you, a malevolent Anti-god.

They set traps to catch each other unawares,

Although the Knights and Rooks could hardly have cared

Whether they happened on a dark or empty field:

For thistle will grow on either one!

The angels laughed at the demons’ false moves

But the demons took comfort in the philosophical discovery

That sooner or later everything would crumple into nothing.

Then the rivals tired of their mockeries,

Folded up their chess board and sat down to bingo,

Where the chances are even and there are no Queens or Pawns.

-

For Corinna Psakian (Коринне Псакян)[108]

Not in waking reality, but with old fidelity

I enter the cities of China

Bringing all my tears

To that sad land, unhurried and sedate.

And there, in my dream, before dear Corinna,

Prostrate in the dust, I burn with shame:

For her alone I never wrote a sonnet –

But penitent, I come with these verses

Or a wreath of late dahlias

Into small, gray Harbin,

Where golden youth slumbers,

Immortal only in my memory.

And you are there, enchantress of China,

Pearl of unreturning days.

4. Letter of April 4, 1974 from Pereleshin to the U. S. Consul in Rio de Janeiro

This unpublished letter to the U. S. Consul in Rio de Janeiro was written by Pereleshin the day after he received his American visa to visit Austin.

Pereleshin’s visit to Austin was his second trip to the United States. In 1950 he came to the U. S. from China with an immigrant’s visa; but upon his arrival in San Francisco he was arrested, “quarantined” for three months, and deported back to China. He was suspected of being “a special political correspondent” of TASS. Evidently this charge was related to his employment at TASS in Shanghai between 1946–1948. When he applied for a visa to visit Austin in 1974, he encountered great difficulties due to the same problem.[109] His case was investigated by U. S. authorities again. Before his trip to Austin, he had a larger plan “to visit the New York area and to meet with several friends.”[110] In February 1974 he even dreamed of going to Washington, D.C. “to address the distant listeners in Russia through ‘Voice of America’.”[111] But, granting him a visa to enter the U. S., the American authorities limited him to travel to Austin only.[112]

The letter shows Pereleshin’s volatile state of mind after a confrontation with American authorities that evoked painful memories of his detention and deportation in San Francisco in 1950. This incident also explains why in his interview with Sylvester he tended to provide falsified dates regarding his Soviet citizenship, connected as it was with his job at TASS: he was rather careful to reduce the political color of his past. Fortunately, he did not act on his intentions expressed in the letter, but left Rio for the poetry festival in Austin a few days after writing it.[113]

As a document, it shows the poet’s eloquent command of written English. The typed letter is transcribed here without any corrections in spellings or standard English usage. At the end, there is a postscript written in Pereleshin’s hand..

April 4th, 1974.

.

Mr. Donald J. Yellman

Consul of the U.S.A., Rio de Janeiro

Dear Mr. Yellman,

After our short conversation yesterday I went on moving almost mechanically and made reservation with Panamerican. Then I convinced the Brazilian chief of Maritime police that my case was really urgent and my exit permit should be renewed at once. My passport with the U. S. visa stamped in it is at the Maritime police office at this moment.

However, the note in your handwriting – “Austin only – Festival of Poetry” – is burning in my brain. It may be interpreted in a broad sense, or in a narrow sense, but who is to interpret it? Any clerk, any cop in Austin. If I attend a bridge-party in Austin, it is not connected with Festival of Poetry, and attending it may be considered a misdeed. If the second recital of poetry for which the University promises to pay me is to take place in a suburb, should I attend it? Again, it may be not Austin, but another community!

Suppose an unitedstatesian is admitted to Rio de Janeiro under similar formula: “Rio de Janeiro só – Festival do Canto”. Obviously, he will not be free to cross the State border and go to Neteroi, or to Petropolis. Nor will he be free to attend a football game as it is not on the programme of the Festival of Song.

Such strings attached, or handcuffs, would bring about an unbearable psychological tension. Besides, I would be paid for informal conversations with professors and students of the University. Among them there may be conservative people like myself, or liberals, or admirers of Mayakovsky, or even “pinkies”. How could I tell them apart at a glance? If somebody seeks my company once or twice and is later found a communist sympathizer, will the fact of seeing him or her twice not be held against me at a later stage, and perpetually?

One of your casual remarks was deeply symbolical. This visit to the USA, you said, was an opportunity for me to show that I am NOT a communist. In my European mind there is a different legal conception. Onus probandi falls on the accuser, not on the defendant. If I am accused of being a communist, the accuser must come forth and supply the proofs. But he remains anonymous and irresponsible. How on earth could you prove that you do not play chess? By not playing chess during a Festival of Song, or a Festival of Poetry? By not playing it for a month, for a year, or for five or ten years?

We Europeans and some Americans (Brazil is an American nation) think that one absurd point in a denunciation invalidates the whole concoction. In the denunciation concocted against me in 1950 I was accused of having helped general Blücher (then acting under an assumed name) to organize Chinese communist party in 1920.[114] I certainly was a precocious child, as in 1920 I was aged seven.

A denunciation containing such a statement ought to have been thrown in a waste-paper basket the next minute. But it was not. The inquisitors’ mentality is different: this one point may be idiotic, but the rest may be true? And a long investigation follows, and the co-organizer of the Chinese communist party is held in jail politely called Detention house for several months, interrogated and deported to “the country of origin” (i.e. to communist China – and what China it was back in 1950!) as a person “soupçonné d’etre suspect”, and never left in peace.[115] Even if he is a contributor to two Russian anticommunist newspapers and to several equally militant anticommunist journals, some of them published in the USA, even if his signed articles and poems only show him as an irreconcilible enemy of communist dictatorial regimes, the stigma remains and the suspicion of double-dealing, somewhat illogically, becomes deeper and deeper.

The USA is traditionally associated with freedom. In my lifetime I have only seen the other side of the medal. Detention house in 1950, a straightjacket in 1974.

The treatment I have been having at the hands of the USA immigration authorities may be looked at as a certain honour, however tragic, and a kind of distinction, if not of singularity. I fully understand the bureaucratic knights’ faithfulness to their unimaginative Lady. They have one-track minds, and they understandably could not care less for my Lady – the Russian poetry – free and idealistic – who has nothing to do with such “adepts” as the yevtushenkos or the narovtchatovs often visiting the USA, broadly advertised and feted.

I am sending a copy of this letter to Miss Carol L. Anshütz of Slavic Department, the University of Texas at Austin not with an intention to foster bitterness on anybody’s part, but simply to explain my motives in finally declining the University’s invitation to take part in the Festival of Poetry to be held on April 11-13, 1974.

Let me take this unique opportunity to thank you once more for your exceptional goodwill, efficiency and persistence.

Indeed, the Festival of Poetry was a chance to assert my vision of and my views on poetry. It might help the general public in the USA to discover the poetry of the Russian refugees. Personally, for me it might be an opportunity to survive as a significant poet a generation or two after I eventually disappear. Believe me, I am not in despair, as despair is the natural state of my mind. To conclude, let me quote two lines from a better bard: “For the crown of our life as it closes / Is darkness, the fruit thereof dust.”[116]

Yours very sincerely

V. F. Salatko-Petryshche.

.

[Written in Pereleshin’s hand]:

Dear Miss Anschuetz, The whole adventure is too painful to speak of it, so I am sending this copy. Defeated once more, I shall have to lick my wounds until they are healed. After all, I am Brazilian, and free.

Please look into the problem of my “Sacrifice” ordered by your University Library. I want U.S. $21.00 to cover the cost and postage, or – and better – I want the book back, provided it is not spoiled by seals and numbers.

Thank you and everybody in the University: S. Monas, C. Middleton, Mrs. Kirtley.

Yours.

/s/ Valerii Pereleshin

cc: Miss Carol L. Anschütz

Slavic Department

University of Texas at Austin.

Literature

Listed here are Pereleshin’s collections of original poetry in Russian. Other sources consulted are identified in the Notes below as they occur.

V puti. Harbin: Zaria, 1937. [Pereleshin’s first four books were published by the poet’s mother using the „Zaria“ publishing house.]

Dobryi ulei. Harbin: Zaria, 1939.

Zvezda nad morem. Harbin: Zaria, 1941.

Zhertva. Harbin: Zaria, 1944.

Iuzhnyi dom. Frankfurt/Main: Izdanie avtora, 1968.

Kachel’. Frankfurt/Main: Possev-Verlag, 1971.

Zapovednik. Frankfurt/Main: Possev-Verlag, 1972.

S gory Nevo. Frankfurt/Main: Possev-Verlag, 1975.

Arièl’. Frankfurt/Main: Possev-Verlag, 1976.

Tri rodiny. Paris: Al’batros, 1987.

Iz glubiny vozzvakh. Holyoke, MA: New England Publishing Co., 1987.

Dvoe—i snova odin?. Holyoke, MA: New England Publishing Co., 1987.

Vdogonku. Holyoke, MA: New England Publishing Co., 1988.

Poèma bez predmeta. Holyoke, MA: New England Publishing Co., 1989.

Russkii poèt v gostiakh u Kitaia 1920–1952. Edited and annotated by Jan Paul Hinrichs. The Hague: Leuxenhoff, 1989.

Notes

- In his report to the Bureau for the Affairs of Russian Émigrés (Harbin, 1944, The State Archive of Khabarovsk Region, f. 830, op. 3, d. 15841), Pereleshin’s father claims that he is Byelorussian. In his youth Pereleshin learned from his mother that the Salatko-Petryshche family was Polish, but later found out that it was Byelorussian. In a letter to his Harbin friend Peter Lapiken dated 23 July 1975 he says: “I also think my surname is Byelorussian” (Novyi zhurnal, No. 234, 2004, p. 184). In his narrative poem Poèma bez predmeta he states: “Byelorussia is my motherland” (Canto I: 11). He also wrote an article “About the Kin of Salatko-Petryshche.” This unpublished article is in the Valerii Pereleshin archive held at Leiden University Library in the Netherlands (BPL 3261/37).

- According to his own report to the Bureau for the Affairs of Russian Émigrés (Harbin, 1944), he was born 3 June 1889.

- Now called Ulan-Ude.

- Pereleshin’s younger brother published poems under the pseudonym Viktor Vetlugin in the Harbin paper Churaevka and the journal Rubezh. At the time of this interview, he was an engineer living in Rio de Janeiro. In his report to the Bureau for the Affairs of Russian Émigrés (Harbin, 1938) he states that he was born in Irkutsk (State Archive of the Khabarovsk Region, f. 830, op. 3, d. 15841).

- It must have been 1942 when Pereleshin last saw his father: he left Harbin in April 1942 and never went back there again.

- The Company of the Chinese Eastern Railway (КВЖД).

- Sentianin was a liberal Russian aristocrat and something of a freethinker à la Voltaire. His parents’ estate was in the same neighborhood as the Spasskoe estate of the Turgenevs. Before he came to the Far East he was the publisher of the newspaper Orlovskii vestnik in Orel. Among his employees was the young Ivan Bunin, just then beginning his writing career as a journalist. Even in those days, Sentianin used to say, Bunin had foreseen his future greatness as a writer, and treated his colleagues (including the editor) with some haughtiness and even contempt [Pereleshin’s note].

- She wrote some stories, too, e. g. “Siren’ tsvetet” (Lilacs in Bloom), written jointly with Valerii in June, 1937 [Pereleshin’s note]. The article about Harbin writers in Rubezh signed “E. Siniatina” (Nos. 645-6 in Ludmila A. Foster’s Bibliografiia russkoi zarubezhnoi literatury, 1918-1968: Boston, G. K. Hall, 1970; hereafter cited as Foster) is not in fact by her but was written by Pereleshin in Peking: see his letters to his mother dated 6 April and 12 April 1940 (Leiden University Library, BPL 3261/1).

- At this time the school had been renamed The State Law School of the ORSM (Osobyi raion Severnoi Man’chzhurii, an administrative geographical designation used under the Japanese occupation).

- After St. German of Kazan’ and Svivaisk, an archbishop who was killed by order of Ivan the Terrible [Pereleshin’s note].

- It was Pereleshin’s friend Lidiia Khaindrova, who knew the archbishop personally, who helped him obtain this job. She will be introduced into Pereleshin’s narrative below, as one of the poets in the “Friday” group in Shanghai.

- Pereleshin was working toward a master’s degree at the theological institute in Harbin. Though he took his exams and nearly completed a thesis, he never submitted a final revised version of the thesis and thus he did not receive the degree. The copy in his archive at Leiden is considered a draft: see note 41 below.

- Al’bert Nikolaevich Benois (1852–1937) was the older brother of the more famous Aleksandr Nikolaevich Benois (1870–1960), leader of the “World of Art” movement. Al’bert was an artist himself (an eminent watercolorist) who gave drawing lessons to his younger brother.

- Korostovets accompanied Witte to New Hampshire as the count’s secretary during the Portsmouth negotiations in 1905. His memoirs are interesting, showing some of the diplomatic tricks the Russians employed to get American public opinion on their side, such as the tactic of having Witte and Korostovets attend Protestant church services every Sunday [Pereleshin’s note].

- Actually, there were not many Russians in Peking at that time. Those who took shelter there were the so-called Albazintsy. At the end of the 17th century, after the conflict between Russia and China in the borderlands, more than one hundred Cossacks who were captured by the Chinese army decided to settle in the Chinese capital and thus moved to Peking, where they were given a temple to be used as an Orthodox church and allowed to marry Chinese prisoners. They settled in the area around Beiguan, the location of the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission. Even today some descendants of the Albazintsy still live in that area and bear certain adapted Chinese surnames. Most of Pereleshin’s friends in Peking were descendants of the Albazintsy. Among those who sought shelter at Beiguan there were also Chinese who were baptized.

- In the letters to his mother during his stay in Peking Pereleshin never mentioned taking private Chinese lessons from his ecclesiastical colleagues. One of his Chinese teachers mentioned in those letters is a Mr. Tang, who did not belong to the Mission (Leiden, BPL 3261/1).

- For Pereleshin’s account of Porshnev’s death, see “Arkhimandrit Nafanail (Porshnev)” in Valerii Pereleshin, Russian Literary and Ecclesiastical Life in Manchuria and China from 1920 to 1952, ed. Thomas Hauth, The Hague, Leuxenhoff, 1996.

- This matter will be discussed in more detail in the commentary following Pereleshin’s narration.

- One of his pupils was Baroness Ludmila Fitingof, who later married the American Slavist Alex M. Shane. Pereleshin wrote a review in the journal Grani of Shane’s book on Zamiatin (The Life and Works of Evgenij Zamjatin, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1968). [Pereleshin’s note].

- Peterets was 6 or 7 years older than Pereleshin. He died of TB in Shanghai in 1944. In the anthology Russkaia poèziia Kitaia, compiled by Ol’ga Bakich and Vadim Kreid, Moscow, 2001, his place of birth is given as Rome, but his mother’s family was from Vladivostok. They both held Czech passports and moved to Harbin in the early 1920s.

- Andersen is in Literaturnaia èntsiklopediia russkogo zarubezh’ia (1918–1940), Tom 1, Pisateli russkogo zarubezh’ia, Moscow, ROSSPEN, 1997, pp. 29-30 (the title given there for her 1940 book of poems, Po zelenym lugam (On Green Meadows), is erroneous). For more recent information about all the women poets in the “Piatnitsa” group, see Olga Bakich and Carol Ueland, “The eastern path of exile: Russian women's writing in China,” in Adele Marie Barker and Jehanne M. Gheith, eds., A History of Women's Writing in Russia, Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- She broadcast a VOA program in May 1974 about Pereleshin’s participation in the Austin poetry festival, with a tape of him reading poems which he brought with him from Brazil and mailed to her.

- More titles will be found in Bakich and Ueland, p. 329, cited above in Note 21.

- Vitkovskii first heard about Pereleshin in 1968 from Khaindrova’s half-brother Levan Khaindrava, who was born in Harbin, returned to the USSR from Shanghai in 1947, and became a writer. Khaindrava is the original Georgian name of the family, but Lidiia Russified it to Khaindrova.

- As indicated, she didn’t die until 1960.

- Pereleshin thought Ludmila Foster confused the Shanghai Vladimir Pomerantsev with another Soviet writer. The birth years are different (1907–1971). The Pomerantsev Pereleshin knew grew up in Harbin, then was in Shanghai: “according to rumors, he lives in Kemerovo and supposedly doesn’t like writing letters.”

- Mary von Krusenstern-Peteretz wrote an article on the "churaevtsy" in Vozrozhdenie, 1968, Vol. 204, pp. 45-70 [Pereleshin’s note].

- Pereleshin’s poems on each theme and where he later placed them are listed below. If the title of the poem is different from the theme-word, that is indicated after the name of the volume in which it occurs. If nothing is indicated, it means the poem had not yet been included in a book. The poems were written between April and November 1944; all of them were published in Ostrov (see note 30 below).